DERMATOLOGIC URGENCIES AND EMERGENCIES

LESLIE CASTELO-SOCCIO, MD, PhD

GOALS OF EMERGENCY CARE

The goals in treating dermatologic conditions are to recognize signs of systemic illness and complications such as secondary infection.

KEY POINTS

The ability to describe a rash precisely and accurately will dramatically improve the likelihood of a correct diagnosis.

The ability to describe a rash precisely and accurately will dramatically improve the likelihood of a correct diagnosis.

Key features of the history include duration of the rash (acute or chronic), initial distribution, extent of spread (generalized or localized), ill contacts (including sexual partners), and any associated systemic symptoms, including fever.

Key features of the history include duration of the rash (acute or chronic), initial distribution, extent of spread (generalized or localized), ill contacts (including sexual partners), and any associated systemic symptoms, including fever.

Key features of the physical examination include a careful systematic inspection of all mucocutaneous surfaces, with special attention paid to involvement of the oropharynx, palms and soles, extensor or flexor surfaces, scalp, and trunk.

Key features of the physical examination include a careful systematic inspection of all mucocutaneous surfaces, with special attention paid to involvement of the oropharynx, palms and soles, extensor or flexor surfaces, scalp, and trunk.

RELATED CHAPTERS

Signs and Symptoms

• Rashes: Chapters 61 to 65

Medical, Surgical, and Trauma Emergencies

• Infectious Disease Emergencies: Chapter 102

Clinicians are often confronted with a skin rash or skin lesion. An accurate diagnosis depends on a systematic approach that requires assessing the skin carefully and knowing dermatology, terminology, morphology, and differential diagnoses. Although not always diagnostic, morphology and configuration of cutaneous lesions are important parts of categorizing and making a differential diagnosis. Terminology is an important part of this process. Descriptors can be divided into primary and secondary. Primary descriptors include macules (flat <10 mm), papules (raised <10 mm), patches (flat <10 mm), plaques (raised >10 mm), nodules (solid lesion 0.5 to 2 cm), pustules (elevation with white material), abscesses (elevated lesion >10 mm with purulent material), wheals (elevated lesion with local transient edema), vesicles (elevated lesion <10 mm containing fluid), and bullae (elevated lesion >10 mm containing fluid). Secondary descriptors include crust, scale, fissuring, erosions, ulceration, umbilication, excoriation, atrophy, lichenification, and scar. In addition to these descriptions it is also important to understand the distribution of the rash or lesion. Distribution characteristics include localized, blaschkoid (following lines of embryologic development), widespread, and photodistributed (predilection for sun-exposed areas). Characterizing a rash or lesion using these descriptors narrows the differential diagnosis significantly. The following sections of this chapter will divide skin changes by their primary descriptor and then will provide a framework for adding secondary characteristics to improve diagnosis.

PAPULES

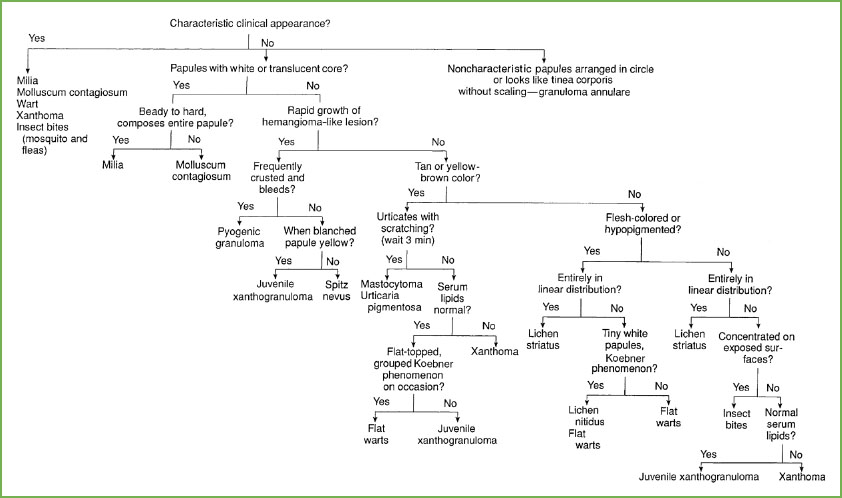

Papules can be quite varied and the following algorithm is used to help practitioners diagnose varying papular lesions (Fig. 96.1).

Papules with a Characteristic Appearance

Many conditions can be diagnosed on sight. For example, the experienced eye can easily distinguish milia from molluscum contagiosum (MC) and warts from the uncommon xanthoma. Several clues make the process of separating these entities from one another easier such as color, distribution, and patient characteristics. Skin biopsy is a valuable tool available to the dermatologist and may be required to differentiate many of the entities discussed here.

Milia

Milia are 1- to 2-mm firm, white papules. They are produced by retention of keratinous and sebaceous material in follicular openings. Newborns often have milia on their face. They frequently disappear by the age of 1 month. Milia can also arise from skin trauma, and can be seen in scars after burns and in healed wounds in patients with blistering disorders like epidermolysis bullosa. Persistent milia may be a manifestation of the oral–facial–digital syndrome, hereditary hypotrichosis (Marie Unna type), and certain rare ectodermal dysplasias (Basan’s syndrome). Because lesions that are not associated with syndromes disappear spontaneously, no therapy is indicated.

Molluscum Contagiosum

The lesion, produced by the common poxvirus, is a papule with a white center (Fig. 96.2). It occurs at any age during childhood. It is more common in swimmers and wrestlers. Patients with atopic eczema are especially susceptible. Most lesions resolve in 6 to 9 months, but some may persist for more than 3 years. Spread is by autoinoculation.

FIGURE 96.1 Approach to diagnosis of papular lesions.

Lesions can be single or numerous and favor intertriginous areas such as the groin. They are usually 2 to 5 mm in diameter, but several can coalesce and form a lesion 1.5 cm in diameter. They may become inflamed, which sometimes herald spontaneous disappearance. Often when inflamed they look “infected” but culture is usually negative. At times, an eczematous reaction occurs around some lesions.

FIGURE 96.2 Child with lesion of molluscum.

Since spontaneous resolution is common, treatment, if elected, should be gentle. Removal of the white core will cure the lesion. This treatment can be performed by applying a local anesthetic cream (e.g., EMLA or LMX-4) under occlusion to the lesion 1 to 2 hours before treatment. This procedure will anesthetize the area and allow the physician to prick the skin open over the core with a 26-gauge needle, and squeeze the core out with a comedone extractor. Multiple light touches with liquid nitrogen can also be effective. With widespread lesions, nonpainful procedures are preferable as multiple painful treatments will cause great fear in the patient and make future visits to a physician difficult for the family. Application of 0.1% tretinoin cream one to two times daily may induce enough inflammation to hasten the host’s immune response or cause extrusion of the central core but caution should be observed since tretinoin may exacerbate secondary eczematization around molluscum lesions. A dilute formulation of cantharidin, a natural toxin derived from the blister beetle, can be used successfully to treat molluscum. Cantharidin can be applied to individual molluscum lesions for 1 to 4 hours and then washed off. The medication is generally painless when applied but may result in subsequent blistering of treated areas and should be avoided on the face or genital areas.

Warts

Warts affect 7% to 10% of the population and are one of the most common dermatologic problems encountered in pediatrics. The peak incidence is during adolescence. Sixty-five percent of common warts disappear spontaneously within 2 years, and 40% of plantar warts disappear within 6 months in prepubertal children. However, immunosuppressed patients may experience extensive spread of the lesions.

The common wart resembles a tiny cauliflower. Lesions disrupt the natural skin lines and may also manifest with small black dots, representing thrombosed capillaries. The shape of the wart varies with its location on the skin. They may be long and slender (filiform) on the face and neck or flat (verruca plana) on the face, arms, and knees. When located on the soles, they are called plantar warts, and when in the anogenital area, they are referred to as condyloma acuminata.

The tendency for recurrence of warts makes the treatment of this condition frustrating. Because most warts disappear spontaneously with time, procedures that are least traumatic for the child should be attempted first. The simple, nontraumatic method of airtight occlusion with plain adhesive tape or duct tape for 1 month has been shown to be successful on many occasions. Topical application of 17% salicylic acid in flexible collodion (Duofilm) or duct/occlusive tape is good for home use. Plantar warts can be treated with 40% salicylic acid. When simple methods are unsuccessful, touching the warts with liquid nitrogen or volatile cryogens such as dimethyl ether, propane, or isobutane (Verruca Freeze) for 10 to 30 seconds or surgical removal can be attempted on a 2- to 4-week schedule until the lesions clear completely. Both procedures are painful.

Anogenital warts can be treated with topical preparations such as podophyllotoxin gel (Condylox) or imiquimod cream (Aldara). Podophyllotoxin gel is applied on the condylomata three consecutive nights each week while imiquimod is used every other night three times weekly. Both agents may be used for up to 3 months or so or until the warts clear. Topical cidofovir in 1% or 3% preparation can also be used for warts and molluscum. Child abuse should be considered in any child with genital warts but keep in mind that maternal transmission can occur during delivery.

Xanthomas

Papules, plaques, nodules, and tumors that contain lipid are called xanthomas. These lesions can appear on any skin surface and are often associated with disturbances of lipoprotein metabolism.

Insect Bites

Mosquitoes are probably the most common cause of insect bites in children, followed closely by fleas (Fig. 96.3) and bed bugs. Mosquito bites are generally limited to the warm months of the year. In contrast, fleabites, which predominate from spring to fall, can also occur during the winter months as a result of cats, dogs, and rodent who live indoors.

The distribution of lesions is a valuable clue in making the diagnosis of mosquito or fleabites. Insect bites generally involve the exposed surfaces of the head, face, and extremities. The lesions are usually urticarial wheals that occur in groups or along a line on which the insect was crawling. Some lesions may manifest a central punctum. On occasion, both mosquito bites and fleabites can cause blistering lesions. These lesions are not caused by secondary infection but rather by an immune response to the bite. Certainly, excoriation with resulting secondary infection with Staphylococcus aureus or Group A streptococci can complicate a simple bite.

FIGURE 96.3 Insect bite in a child.

Unfortunately, no specific treatment exists for insect bites. Antihistamines, calamine lotion, or topical steroids have a limited or temporary effect. Prevention through the prophylactic use of insect repellents and protective clothing offers the best solution. Obviously, elimination of the biting insects by treatment of the homes with insecticides or treatment of the infested animals is important. For additional information about insect bites, see Chapter 62 Rash: Vesiculobullous.

Tick Bites

Tick bites usually cause only local reactions. Erythema migrans is the characteristic rash of Lyme disease and looks like large bull’s eye; the rash does generally appear 7 to 10 days post tick exposure but the range is 3 to 30 days. Rarely, tick bites are associated with significant systemic illness, including Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), tick paralysis, and Lyme meningitis.

When ticks are removed, it is important not to leave fragments of the mouthparts in the skin or to introduce body fluids containing infectious organisms. Various methods have been recommended for removal of ticks from the skin. The safest method is to use a blunt-curved forceps, tweezers, or fingers protected by rubber gloves. The tick is grasped close to the skin surface and pulled upward with a steady even force. The tick should not be squeezed, crushed, or punctured. If mouthparts are left in the skin, they should be removed.

Spider Bites

Loxosceles reclusa, or the brown recluse spider (Fig. 96.4), found most commonly in the south central United States (from southeastern Nebraska through Texas, east through southern Ohio and Georgia), is responsible for most skin reactions caused by the bite of a spider. This spider is small, the body being only 8 to 10 mm long, and bears a violin-shaped band over the dorsal cephalothorax. The venom contains necrotizing, hemolytic, and spreading factors.

FIGURE 96.4 Spider recluse.

The initial symptoms include mild stinging and/or pruritus. A hemorrhagic blister then appears, which can develop into a gangrenous eschar. Severe bites can cause a generalized erythematous macular eruption, nausea, vomiting, chills, malaise, muscle aches, and hemolysis. Treatment includes tetanus prophylaxis, the use of dapsone in selected cases where there is apparent necrosis (but never in patients with G6PD deficiency), and surgical removal of the necrotic area to prevent spread of the toxin. Antibiotics are indicated if there are signs of secondary infection. Some authors recommend corticosteroids if the patient presents within 12 hours of a bite but the efficacy of this approach is unproven. An antivenom exists if there are systemic signs.

Scabies Infestation

Please see Chapter 62 Rash: Vesiculobullous for more details. The cardinal symptom of any infestation with scabies is pruritus. Two clues should be considered when attempting to make this diagnosis: (i) Distribution (red papules with concentration on the hands, feet, and folds of the body, especially the finger webs and genital areas) and (ii) involvement of other family members. It is important not only to ask other family members if they have pruritus but also to examine their skin. In contrast to adults, infants may develop blisters and exhibit lesions on the head and face.

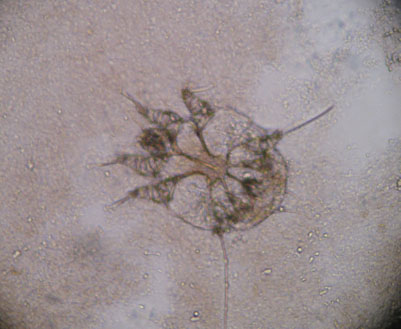

FIGURE 96.5 Scabies mite.

The diagnosis is made by scraping involved skin and looking for mites under the 10× microscope objective (Fig. 96.5). Once an infestation occurs, it usually takes 1 month for sensitization and pruritus to develop.

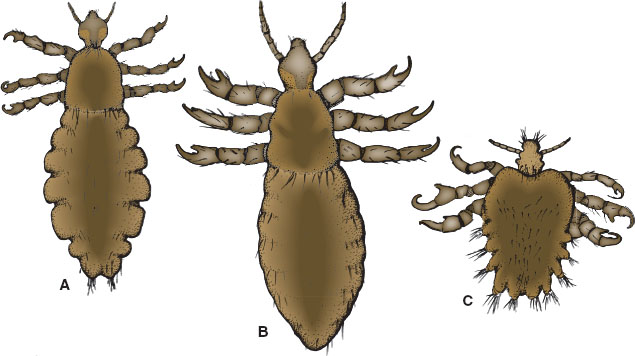

Louse Infestation

Three forms of lice infest humans: (i) The head louse, (ii) the body louse, and (iii) the pubic or crab louse (Fig. 96.6). The major louse infestation in children involves the scalp and causes pruritus. The female attaches her eggs to the hair shaft. The egg then hatches, leaving behind numerous nits that resemble dandruff. Secondary infection can occur from vigorous scratching. Body lice generally reside in the seams of clothing and lay their eggs there. They go to the body to feed, particularly the interscapular, shoulder, and waist areas. Red pruritic puncta that become papular and wheal-like then occur. Pubic lice occur in the genital area, lower abdomen, axillae, and eyelashes. Transmission is usually venereal. Blue macules (maculae caeruleae) that are 3 to 15 mm in diameter can be seen on the thighs, abdomen, or thorax of infested persons. These macules are secondary to bites.

FIGURE 96.6 Louse.

Because the body louse resides in clothing, therapy consists mainly of disinfecting the clothing with steam under pressure. Pediculosis capitis is usually effectively treated with 1% permethrin or pyrethrin creme rinse though resistance to this medication is not uncommon. The patient’s hair should be shampooed, rinsed, and toweled dry. Enough medication to saturate the hair and scalp is applied. The medication is washed out after 10 minutes. Additionally benzyl alcohol–containing products (Ulesfia) and topical ivermectin (SKLICE) products can also be used. Patients with resistant disease may also respond to topical petrolatum applied to hair and scalp nightly for 1 week as a lice suffocant or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole given orally for 5 to 7 days, which kills the symbiotic parasite present in the GI tract of head lice. Pediculosis pubis is best treated with the same permethrin or pyrethrin preparations used for head lice. Any nits are removed with a fine-toothed comb. The safest treatment for lice in the eyelashes is the application of Vaseline twice daily for 8 days. The lice stick to the Vaseline, cannot feed, and die. Another treatment alternative is physostigmine ophthalmic ointment, although it may carry more significant toxicity.

Vascular Papules and Nodules

Vascular papules and nodules can be congenital or acquired. Those in infants generally fall in the category of benign with hemangiomas being most common. Other vascular nodules including kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas and sarcomas should be considered for vascular papules or nodules that feel firm or do not follow the natural history of infantile or congenital hemangiomas. See further discussion in Chapter 64 Rash: Neonatal. Acquired lesions include Spitz nevi and pyogenic granulomas.

Spitz nevus. Spitz nevi appear suddenly between 2 and 13 years of age. Preferred sites of growth include the cheek (15%), shoulder, and upper extremities (Fig. 96.7). The lesion has a pink to red surface because of numerous dilated blood vessels. Pressure produces blanching of this pink to red color. The lesions can reach a size of 1.5 cm in diameter but are completely benign. Pigmented Spitz nevi, another variant of Spitz nevi, often appear black in the skin rather than pink-red, and their appearance is often worrisome for malignant melanoma. Because the histologic appearance of these lesions can be confused easily with a malignant melanoma, an experienced histopathologist should interpret the findings. Most clinicians still recommend that Spitz nevi be removed surgically.

Pyogenic granulomas. Pyogenic granulomas (Fig. 96.8) are bright red to reddish-brown or blue-black pedunculated, vascular papules/nodules ranging from 0.5 to 2 cm in size that develop rapidly at the site of an injury, such as a cut, scratch, insect bite, or burn. Pyogenic granulomas occur commonly in children and young adults, usually on the fingers, face, hands, and forearms.

FIGURE 96.7 Spitz nevus.

They bleed easily. Generally, they are asymptomatic. Because spontaneous disappearance is rare, the lesions must be removed by curettage, excision, electrosurgery, cryosurgery, laser surgery, or some combination of these various modalities. Management of acute bleeding may include chemical (e.g., aluminum chloride or silver nitrate though silver nitrate can leave a tattoo) or electrical cautery, placement of constrictive sutures, or full-thickness excision and suturing.

Yellow, Tan, or Brown Papules

Many papules are yellow tan or brown. The yellow, tan, and brown papules include the lesions seen in urticaria pigmentosa (see Chapter 64 Rash: Neonatal), flat warts, xanthomas, insect bites, juvenile xanthogranulomas as well as melanocytic nevi.

One way to differentiate the various papules from one another is to scratch them. If hiving of a scratched lesion (Darier sign) occurs within a short period of time (3 to 5 minutes), the lesion contains mast cells (i.e., a mastocytoma or urticaria pigmentosa) (Fig. 96.9). Make sure to scratch normal skin to rule out the presence of dermatographism. The latter condition will produce a false-positive Darier sign. When no urtication occurs, a biopsy may be helpful. Flat warts tend to be grouped, are flat topped, and can be autoinoculated in scratch lines (pseudo-Koebner phenomenon). Lesions characteristic for JXGs are not flat topped, tend to be singular in number (or when multiple are scattered about), and do not demonstrate the Koebner phenomenon (recapitulation of the eruption in traumatized areas) (Fig. 96.10). JXG lesions may also look like xanthomas. Unlike xanthomas, however, abnormal lipid levels do not occur with JXGs.

FIGURE 96.8 Pyogenic granuloma.

FIGURE 96.9 Urticaria pigmentosa with Darier sign.

Mastocytoma, Urticaria Pigmentosa

These are red/brown papules that urticate. For additional information please see Chapter 64 Rash: Neonatal.

FIGURE 96.10 Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG).

Juvenile Xanthogranulomas

Juvenile xanthogranuloma. JXGs can be confused with urticaria pigmentosa or xanthomas. Numerous yellow or reddish-brown papules appear on the face and upper trunk in the first year of life. The number of lesions may increase until the child is 18 months to 2 years of age. Serum lipid levels are normal, and the Darier sign (urtication after scratching) is negative. The lesions often disappear spontaneously after 2 years of age; therefore, intervention is generally unnecessary. When JXGs are multiple, particularly on the head and neck, evaluation of the eyes for intraocular JXGs is recommended because of their potential for visual impairment. The presence of JXGs in a young child with neurofibromatosis (type 1) has been a marker associated with an increased risk of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia.

Flesh-colored Papules

Many entities may present as flesh-colored papules. Here we will highlight lichen striatus and lichen nitidus. When the papules are arranged linearly, streaming down an extremity or across the face or neck, lichen striatus should be considered. If the papules are not arranged linearly but are tiny pinpoint, flesh-colored papules, lichen nitidus should be considered, especially if a Koebner phenomenon is present. Flat warts may be flesh colored as well.

Lichen Striatus

Lichen striatus is an asymptomatic eruption of unknown cause. The flat-topped papules are arranged linearly and may be confluent. Lesions may occur in a wide band but remain characteristically linear or more accurately curvilinear patterns corresponding to lines of Blaschko. The lesions are flesh colored to erythematous in Caucasians and hypopigmented in African Americans. The eruption follows the long axis of an extremity (Fig. 96.11) or may involve any other part of the skin surface (especially the face). Because the eruption resolves spontaneously within 2 years, no treatment is necessary.

Lichen Nitidus

Lichen nitidus is characterized by tiny, pinpoint, flat-topped, flesh-colored papules (Fig. 96.12). The papules are often grouped and are found in scratch lines (i.e., the Koebner phenomenon). Although any skin surface may be involved, the trunk and genitalia are common sites. The lesions are often asymptomatic but may occasionally itch. The lesions persist for variable periods and generally do not respond to therapy.

If this algorithm for papules has not helped in making a diagnosis, a consultant should be called. Many entities can be difficult to differentiate.

FIGURE 96.11 Lichen striatus.

FIGURE 96.12 Lichen nitidus.

PLAQUES

Annular Plaques

Granuloma Annulare

Granuloma annulare is believed to be an idiosyncratic response to trauma and looks to many like tinea corporis (“ringworm”) without the scale. This skin change may begin as a flesh-colored or violaceous papule that clears centrally as the margins advance, or it may appear as a group of papules arranged in a ring-like configuration (Fig. 96.13). The central portion of the lesion is often dusky or hyperpigmented. The key point on physical examination is the lack of scaling. This physical finding distinguishes granuloma annulare from tinea corporis and cannot be stressed enough. The border is firm on palpation, unlike tinea corporis. The rings can be 5 cm in diameter or larger.

FIGURE 96.13 Granuloma annulare.

A potassium hydroxide test would be definitive in ruling out tinea corporis. It would be difficult to obtain scales from a granuloma annulare lesion using this procedure. It is important to diagnose this entity correctly because one can reassure parents that three-fourths of lesions clear spontaneously within a 2-year period. Recurrences are common until children outgrow this tendency.

Lupus

Neonatal lupus and systemic lupus can sometimes be composed of annular plaques. Lupus has a varied appearance depending on type and whether it is skin limited or systemic. For more discussion please see Chapter 64 Rash: Neonatal for discussion of neonatal lupus and Chapter 62 Rash: Vesiculobullous for discussion of bullous lupus.

NODULES

Nodules in the skin can be difficult to diagnose and many require a skin biopsy. There are a few inflammatory conditions of the skin that are characteristically nodules and should not be missed.

Panniculitis

Erythema Nodosum

Erythema nodosum seems to be a hypersensitivity reaction leading to inflammation of the subcutaneous fat and may be related to infection (streptococci, tuberculosis, coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis), inflammatory bowel disease, sarcoidosis, and medications (e.g., oral contraceptives). The exact immunologic mechanism has not been clarified. The entity occurs predominantly in adolescents during the spring and fall. Women are affected more often than men.

The lesions of erythema nodosum appear as deep, tender, erythematous nodules, or plaques on the extensor surfaces of the extremities. The sedimentation rate is generally elevated and usually returns to normal with disappearance of the eruption, unless an underlying disease is present. The reaction usually lasts 3 to 6 weeks. Treatment should be directed toward the cause when and if established; otherwise, it is symptomatic (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antihistamines). Hospitalization is unnecessary. Corticosteroids should not be used, except in severe cases after an underlying infection has been ruled out.

Cold Panniculitis

Cold panniculitis is caused by cold injury to fat. During the cold of winter, infants and some older children develop red, indurated nodules and plaques on exposed skin, especially on the face. The subcutaneous fat in infants and some children solidifies more readily at a higher temperature than that of an adult because of the relatively greater concentration of saturated fats. Infants who hold ice chips or popsicles in their mouths are also susceptible to this phenomenon. The lesions gradually soften and return to normal over 1 or more weeks. Treatment is unnecessary.

GENERALIZED MACULES AND PAPULES/MORBILLIFORM ERUPTIONS

Morbilliform rashes are common in pediatric practice, and children often present to the emergency department (ED) for their evaluation and treatment. Morbilliform or “measle-like” eruptions are often described as maculopapular rashes.

The causes of morbilliform eruptions rashes are diverse (Table 96.1) and range from benign to life-threatening (Table 96.2). Common causes include viral exanthems and drug reactions. The diagnostic approach to these disorders is based on the presence or absence of fever, characteristic clinical appearance, location, chronicity, and medication history. Some of these conditions have very characteristic clinical appearances (Table 96.3); however, manifestations of these illnesses can be sufficiently variable that a proportion of the cases are difficult to diagnose.

EVALUATION AND DECISION

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree