DENTAL TRAUMA

ZAMEERA FIDA, DMD, LINDA P. NELSON, DMD, MScD, HOWARD L. NEEDLEMAN, DMD, AND BONNIE L. PADWA, DMD, MD

GOALS OF EMERGENCY CARE

Proper diagnosis and management of traumatic dental injuries (TDI) are essential to improve prognosis. Identifying which injuries require immediate referral to a dentist is important for emergency physicians. Since dental injuries involve the head and neck, concomitant neurologic evaluation is an important aspect of emergency care. Although the majority of injuries are the result of accidents, the patient’s history must be carefully reviewed in the context of the physical findings to determine if presenting injuries could be a result of nonaccidental trauma, that is, abuse.

KEY POINTS

TDI are common pediatric emergencies.

TDI are common pediatric emergencies.

Neurologic assessment is an important part of management as injury has been sustained in the head and neck region.

Neurologic assessment is an important part of management as injury has been sustained in the head and neck region.

Jaw fractures, avulsed and displaced teeth, and dental fractures with exposed nerves (pulp) require immediate referral to a specialist.

Jaw fractures, avulsed and displaced teeth, and dental fractures with exposed nerves (pulp) require immediate referral to a specialist.

RELATED CHAPTERS

Resuscitation and Stabilization

• Approach to the Injured Child: Chapter 2

Medical, Surgical, and Trauma Emergencies

• Child Abuse/Assault: Chapter 95

ASSESSMENT OF TRAUMATIC DENTAL EMERGENCIES

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• In patients with TDI, carefully assess for associated injuries to the CNS, cervical spine, orbits, and jaw.

• Airway obstruction in the setting of facial trauma may be the result of an aspirated tooth or blood in the oral cavity and pharynx.

• Mucosal ecchymoses at the floor of the mouth or vestibular area are highly suggestive of mandibular fractures.

• Primary teeth in the process of exfoliation may be confused with TDI.

• Be alert to the possibility of nonaccidental trauma, that is, child abuse, if the history is not consistent with the observed injuries.

Current Evidence

The most emergent concern in a child with dental trauma is to evaluate for associated facial injuries and airway obstruction. Obstruction can result from accumulation of blood in the oral cavity and pharynx. Alternatively, the etiology may be a tooth aspirated by a child, or a fractured mandible causing the tongue to fall backward against the posterior pharynx.

Beyond airway obstruction and life-threatening injuries, trauma to the jaw, dentition, or soft tissues requires careful evaluation and treatment. Inadequate recognition and management of these injuries can lead to suboptimal cosmetic and functional outcomes.

Goals of Treatment

The care of pediatric patients with maxillofacial and dental trauma should follow the basic tenets of emergency medicine, starting with evaluation and management of airway, breathing, and circulation, as well as neurologic compromise. Once stabilized, the emergency physician should perform a thorough extraoral and intraoral examination to identify the presence of injury to the jaws, teeth, and surrounding soft tissue. Recognition of those injuries that require emergent care from a dentist is imperative.

Clinical Considerations

Clinical Assessment

Children with facial injuries are usually frightened and apprehensive. The examination should be organized to include inspection and palpation of extraoral and intraoral structures. Appropriate analgesia can facilitate the examination; procedural sedation may be required in some cases.

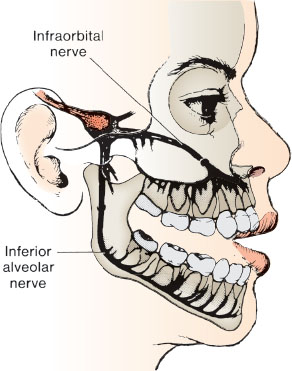

Extraoral examination. The extraoral examination should start with evaluating symmetry of the face in the anterior and profile views. The clinician should carefully note the location and nature of any swollen or depressed structures, the color and quality of the skin, and the presence of lacerations, hematomas, ecchymoses, foreign bodies, or ulcerations. Evaluation of the temporomandibular joints (TMJs) involves observation and gentle bilateral digital palpation while the mouth is opened and closed. There should be equal movement on both sides without major deviations. Mandibular deviation during function or limited mouth opening may signify TMJ injury. Range of motion should not be forced because it may increase the extent of injury. The infraorbital rim should be palpated to ensure it is continuous and intact all the way to the inner canthus of the eye. Examination continues across the zygoma to the nose, palpating for crepitus or mobility. The clinician should inspect for lip competency (the ability of the lips to cover the teeth) because loss of competency may indicate displacement of the teeth from trauma. Attention should focus on the mandible, feeling along the posterior border of the ramus and moving anteriorly along the body to the symphysis, palpating for any discontinuity, mobility, swellings, or point tenderness. The child should be questioned and examined for any evidence of paresthesia or hypoesthesia (numbness) of the lips, nose, and cheeks, which may indicate a fracture through the bony foramen in which the nerve exits. Fig. 113.1 shows the main nerve supply to facial structures.

FIGURE 113.1 Infraorbital and inferior alveolar main nerve supplies the teeth.

Intraoral examination. A good light is essential to inspect the color and quality (i.e., fluctuance or induration) of the lips, gingiva (gums), buccal mucosa, floor of the mouth, tongue, and palate. The gingiva should be pink, firm, and stippled (like a grapefruit skin). The mucosa of the cheeks and floor of the mouth should be pink, moist, and glassy in appearance. The masseter muscle should be palpated by rolling it between fingers placed intraorally and extraorally. Using a gauze pad, the clinician should hold the tongue and lift it gently to better view and examine its dorsal, ventral, and lateral surfaces. Lifting the tongue also allows for a thorough examination of the floor of mouth. Using the thumb and index finger, the clinician should palpate the alveolar ridge in all four quadrants for any swelling, discontinuity, or mobility of the soft tissues and underlying bone. The palate should be examined for any swelling or tenderness. Any soft tissue swelling, ecchymoses, and/or hematoma should be noted. Any inflamed, ulcerated, or hemorrhagic areas, as well as any foreign bodies (e.g., tooth fragments) or denuded areas of bone should be documented. Next, the oral cavity should be inspected for any missing, displaced, mobile, tender, or fractured teeth. These findings are discussed in more detail in subsequent sections.

Radiographic examination. Radiographs are a valuable supplement to the clinical examination. However, in a child with acute orofacial/dental injuries this may be difficult and reserved for a dental office. A chest radiograph may be required if an avulsed tooth is not located. Panoramic radiographs or computed tomography (CT) scans may be indicated to assess for jaw fracture.

SOFT TISSUE INJURY

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• The soft tissues and bones of the lower and midface are well vascularized and bleed profusely when injured.

• Lacerated soft tissues must be evaluated for any debris, foreign body, or tooth fragment.

Current Evidence

Hemorrhage is best controlled by direct pressure and when needed, by ligating any vessels that are easily seen. However, vessels of the face often retract when severed making them difficult to visualize. If there is extensive blood loss, the patient should be assessed for signs of shock (see Chapter 5 Shock). The injured area should be thoroughly examined for a foreign body such as a tooth fragment. This may include obtaining a radiograph or bedside ultrasound before suturing when a foreign body is suspected. Infection and poor wound healing are potential sequelae of such an oversight.

Goals of Treatment

The primary goal for treatment of soft tissue injury is to achieve hemostasis. The highly vascular tissue in and around the mouth can lead to significant blood loss with seemingly mild injuries. Recognizing any embedded foreign materials (e.g., debris, or tooth fragments) is essential to allow wound healing and reduce the likelihood of complications. Injuries to the buccal mucosa and inner lip are rarely of cosmetic concern given rapid wound healing with minimal risk of scarring. Vermillion border injuries require meticulous alignment for optimal cosmetic outcome, while select intraoral lesions do not require any repair at all.

Clinical Considerations

Management of soft tissue injuries of the oral cavity follows the same emergency care principles used for extraoral soft tissue injuries. Injuries to the lip result in significant swelling after minor trauma. Lacerations of the tongue and frenum bleed profusely because of the richness of their vascularity. However, ligating specific vessels is usually unnecessary because bleeding almost always stops with direct pressure and careful suturing. Frenum lacerations often heal spontaneously without suturing. When a laceration in the oral cavity is more than 6 hours old, decisions regarding primary closure need to consider the relative risk of secondary infection.

Management

Suturing. Suturing the lip must be done carefully to achieve a precise approximation of the edges of the vermilion border to avoid a disfiguring scar. If necessary, the lip must be sparingly debrided. Wounds are generally closed with 5-0 or 6-0 sutures. Nylon sutures may be used in cooperative teenagers; however, fast-absorbing sutures are preferred in younger children given the potential challenge of subsequent suture removal. Through and through and other deep lip lacerations require closure in multiple layers, beginning with approximation of the orbicularis oris muscle using 4-0 chromic and then 5-0 or 6-0 sutures (as above) for the skin and vermilion border. Most superficial tongue lacerations heal without suturing. When necessary, tongue lacerations are usually sutured with 4-0 chromic in superficial wounds and with 3-0 chromic in deeper wounds. With tongue lacerations, it is important to consider the excessive muscular movements that pull at the sutures; therefore, tongue sutures should be made deep into the musculature (see Chapter 118 Minor Trauma).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree