Dental Injuries

Kip Benko

Complaints pertaining to the teeth are common and patients frequently present to the emergency department (ED) for initial care. Complaints range in scope from simple chipped teeth to odontogenic deep space infections or complex maxillofacial injuries. Estimates are that 3 million ED visits for dental-related complaints occurred in the United States between 1997 and 2000 (17). Recent data indicate that these numbers have continued to grow, with more than 830,000 visits in 2009 alone, an increase of 16% compared with 2006 estimates (25). The age group with the highest frequency of dental-related complaints is 18 to 35 years old; however, traumatic dental emergencies are more likely in patients 18 years old and younger (17). The frequency of dental-related visits is expected to increase over the next several years as a larger segment of the population becomes uninsured or underinsured. Although these patients can be frustrating and challenging, the emergency physician (EP) should be equipped to diagnose and treat basic traumatic dental conditions until definitive dental evaluation can be obtained.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Dental injuries in the younger population are often related to falls or accidents as new motor skills are developing. Frequently cited causes of injury to the permanent dentition include assaults, falls, motor vehicle collisions, and sports-related mishaps (7,22). Traumatic dental injuries presenting to the ED usually involves the permanent dentition and most commonly the anterior teeth. Dentoalveolar injuries in adults are also found in association with mandibular and facial fractures. Patients with dental injuries usually present with pain, although bleeding and swelling may be associated with these injuries. Patients may also complain of abnormalities of occlusion or of loosened teeth.

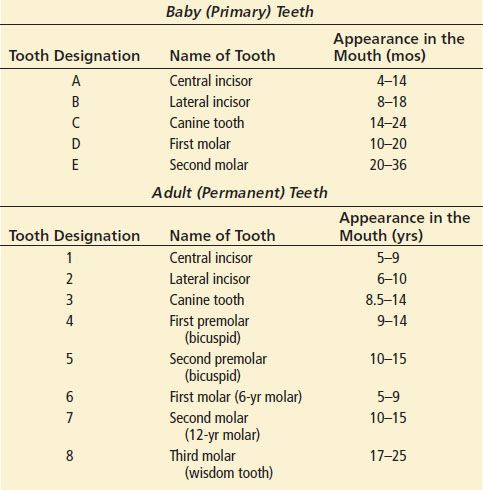

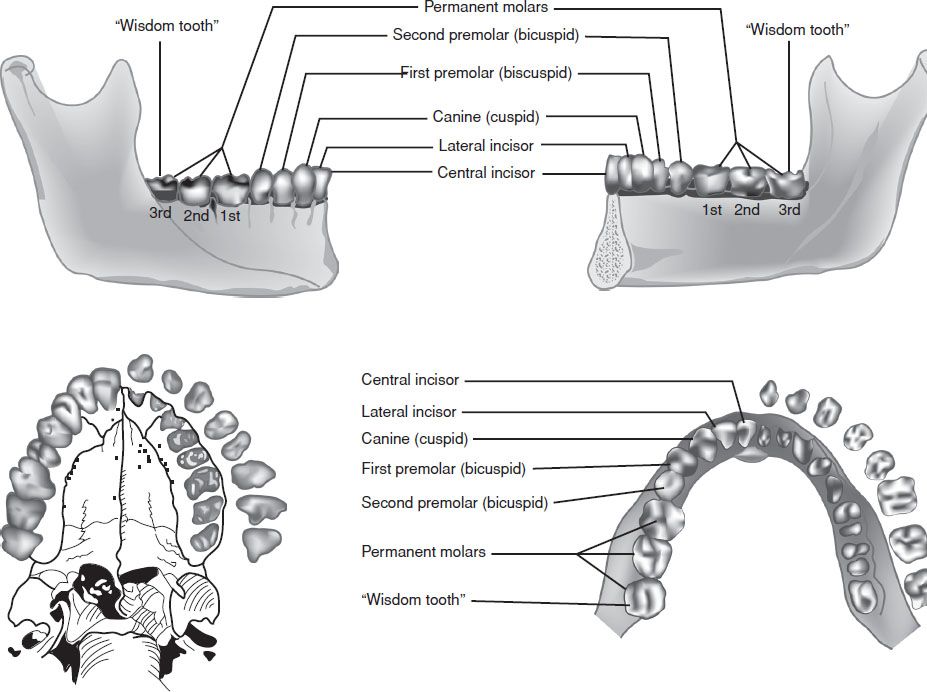

A thorough understanding of dental anatomy allows not only proper ED diagnosis and treatment, but also a more concise and accurate discussion with dental consultants. The adult dentition consists of 32 teeth of which there are four distinct types: incisors (8), canines (4), premolars (8), and molars (12). Starting in the midline, each quadrant has central incisor, lateral incisor, canine (cuspid), two premolars (bicuspids), and three molars, the last of which is the wisdom tooth (Fig. 24.1). The adult teeth are numbered from 1 to 32 as noted in Figure 24.2, although it is more important that the EP be able to describe the tooth involved (i.e., upper left quadrant wisdom tooth) rather than remembering the actual tooth number. Teeth of primary dentition (baby teeth) are, likewise, best described by location and type. The earliest teeth to erupt in a child are the central incisors, usually at 4 to 8 months. The child usually has a full complement of primary teeth by the end of the third year of life. The primary teeth are not numbered but rather lettered as shown in Figure 24.2. The permanent teeth usually start replacing the primary teeth at approximately 5 years of age and this process begins with the incisors (Table 24.1).

TABLE 24.1

Teeth Eruption Times

FIGURE 24.1 Classification of teeth.

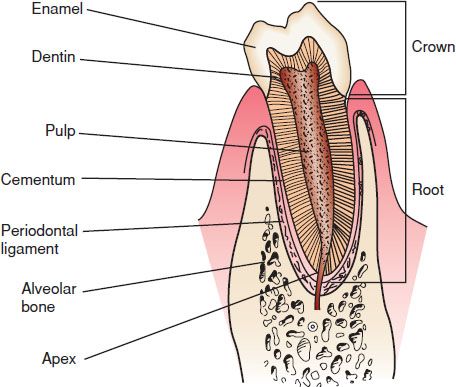

A tooth consists of the central pulp, the dentin, and the enamel (Fig. 24.3). The pulp contains the neurovascular supply of the tooth that carries nutrients to the dentin, a microporous layer that consists of a system of microtubules. The dentin serves to cushion the tooth during mastication and makes up the majority of the tooth. The enamel is the visible portion of the tooth and is considered the hardest part of the body. The tooth may also be described in terms of its crown or root. The crown is that portion covered in enamel and the root anchors the tooth to the alveolar bone.

FIGURE 24.3 The dental anatomic subunits.

The following terms are used to identify the different anatomic surfaces of the tooth and are helpful when describing a specific tooth injury to a consultant.

Facial: Refers to the surface of the tooth that is seen when a person smiles. This is a general term, is applicable to all the teeth, and is sufficient to use when describing an injury, however, the following is more specific and precise.

Labial: Refers to the facial surface of the canines and incisors.

Buccal: Refers to the facial surface of the molars and premolars.

Oral: Surface that faces the tongue or the palate. This is also a general term and is applicable to all the teeth, but the following is more precise.

Lingual: Toward the tongue, the oral surface of the mandibular teeth.

Palatal: Toward the palate, the oral surface of the maxillary teeth.

Approximal /interproximal: The contacting surfaces between two adjacent teeth.

Mesial: The interproximal surface facing anteriorly or closest to the midline.

Distal: The interproximal surface facing posteriorly or away from the midline.

Occlusal: The biting or chewing surface of the premolars or molars.

Incisal: The biting or chewing surface of the incisors and canines.

Apical: Toward the root of the tooth.

Coronal: Toward the crown or the biting surface of the tooth.

The attachment apparatus, or periodontium, consists of two major subunits and is necessary for maintaining the integrity of the normal dentoalveolar subunit.

The gingival subunit consists of the visible junctional epithelium and the gingival tissue.

The periodontal subunit includes the periodontal ligament, alveolar bone, and the cementum of the root of the tooth.

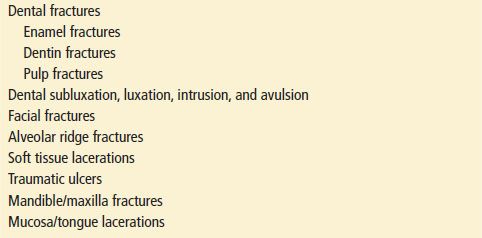

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of traumatic dental injuries is fairly straightforward. The primary concerns are whether the existent trauma could potentially cause airway compromise. Mandibular, maxillary, or alveolar ridge fractures may leave the tongue unsupported or the midface unstable. Each scenario may lead to difficultly when performing intubation or ventilation with a bag-valve-mask. Tongue and mucosal lacerations may cause bleeding severe enough to compromise the airway. It is also important to evaluate potential associated injuries such as traumatic brain injuries, other maxillofacial injuries, or cervical spine injuries.

Trauma to the teeth usually consists of fracture, intrusion, subluxation, (loose, nondisplaced teeth), luxation (displaced teeth), or complete avulsion. Fractures involving segments of teeth usually involve the alveolar ridge as well. The final diagnosis is primarily determined by a meticulous physical examination, accounting for each tooth, portion of the tooth, and integrity of buccal and gingival mucosa. Radiography usually serves a confirmatory role (Table 24.2).

TABLE 24.2

Differential Diagnosis of Orofacial Trauma

ED EVALUATION

The evaluation of dental complaints in the ED consists of a focused, but meticulous, history and physical examination. Important historical information with regard to traumatic injuries includes the following:

When did the incident occur? The timing of the incident is important when evaluating avulsed permanent teeth, as the decision to reimplant the tooth is largely based on the duration that the tooth was out of the socket.

Were any teeth found at the scene? Did the patient experience any coughing or gagging after the injury? This may be suggestive of aspiration of a tooth.

Has the patient been drinking alcohol or using any other drugs, which may alter their level of consciousness (including recreational drugs)? These drugs may increase the likelihood of aspiration, especially if the gag reflex is diminished.

Was there a loss of consciousness?

Does the patient complain of pain? Do the teeth feel as if they are meeting normally? Is the pain associated with occlusion? Mandibular fractures are often worsened with jaw movement and patients will also complain that their teeth do not meet normally. Pain from temporomandibular joint (TMJ) injuries is often referred to the ear. Pain from fractured teeth is made worse with the inspiration of air or contact with hot or cold substances. Alveolar ridge fractures are made worse with any movement of that segment.

Did the patient apply any substance to the teeth to decrease the pain? Over-the-counter anesthetics and topical analgesics can cause sterile abscesses if applied to the pulp or the dentin (12).

Does the patient have a history of dental work with regard to the traumatized tooth?

Is the tooth a primary or secondary tooth? Traumatized primary teeth are managed differently than permanent teeth.

Does the patient have a history of bleeding disorders or allergies to medicines?

A meticulous physical examination is important. Injuries to the dentition and mucosa are easily missed during a casual examination or if the examiner is distracted by more obvious physical findings. The many nooks and crannies of the mouth can easily hide fairly significant sized lacerations, tooth fragments, and other foreign bodies.

The examination should begin with observation and simply talking to the patient; muffling, drooling, and voice change may signify airway involvement. Individuals with mandible dislocations or fractures often talk with a partially open mouth without pursing their lips. External inspection should be performed next. Mandibular dislocations and fractures are associated with asymmetry, deformity, or swelling of the face. The EP should visualize the face from multiple angles to note subtle asymmetries. The opening and closing of the mouth should be smooth and full, with no limitations or hesitations. The face is palpated for crepitus, tenderness, or step-offs. The mandible and entire midface should be palpated with particular attention being paid to the maxilla, zygomas, mandibular condyles, and coronoid processes. The TMJs should be palpated throughout the entire range of motion. There should not be any pops, clicks, or complaints of pain.

The physician should palpate the neck with special attention to the area beneath the mandibular body and assess for swelling or tenderness, and examine the skin for bruising. The oral cavity should be inspected for bleeding, swelling, or tenderness. Each tooth should be accounted for. A tongue blade can be used to visualize the entire mucobuccal fold region. Often, when the buccal mucosa is redundant or if there is swelling secondary to trauma, a two-tongue blade technique is necessary to visualize the entire oral cavity. Using a gloved hand, the EP should palpate the buccal mucosa and the floor of the mouth. Each tooth should be percussed with a tongue blade for sensitivity and palpated with fingers for mobility. Blood in the gingival crevice (where the enamel contacts the tooth) is suggestive of a traumatized tooth or a mandibular or maxillary fracture. The teeth should meet evenly when biting and the patient should be able to exert firm pressure on a tongue blade with his or her molars. The inability to crack a tongue blade bilaterally when it is twisted between the molars (tongue blade twist) is suggestive of a mandibular fracture (1).

The basic evaluation and treatment of most dental emergencies can be performed without any radiographic or laboratory evaluation. Unlike definitive care in the specialist’s office, the ED treatment of tooth and alveolar ridge fractures is usually not changed by information gained from x-rays. Radiographs should be obtained if a tooth fragment is missing and thought to be aspirated or otherwise lodged in the lip or buccal mucosa. Similarly, intruded teeth are not always apparent and x-rays can help distinguish between an intruded and an avulsed tooth.

A panorex and a Towne view are probably the most useful and cost-effective views to obtain when evaluating mandibular trauma in the ED (8,12). The panorex of the mandible shows the mandible in its entirety and demonstrates fractures in all regions, including the symphysis; however, it can rarely miss overriding anterior fractures (18). An occlusal view or CT scan is indicated if this is likely. The Towne view allows slightly better visualization of the condyles and should be used if the condylar regions cannot be visualized adequately with a panorex (8). Coronal CT scanning is more precise and definitive and is often used in the preoperative evaluation, however, CT scanning is usually unnecessary in the ED evaluation. CT scanning should be obtained if multiple facial fractures are suspected or if clinical suspicion is high and standard radiographs are negative or equivocal. If the patient is unable to sit still in the panorex machine or is immobilized, then CT scanning or standard lateral mandibular films should be obtained. Lateral mandibular films have the disadvantage of not visualizing the symphysis well and occlusal films may be required to better evaluate this part of the mandible.

Laboratory work is not necessary for the routine evaluation of dental and and maxillofacial trauma but should be considered on an individual basis. Likewise, bleeding times and coagulation profiles are unnecessary in most individuals, but should be considered if the patient is anticoagulated or the history is compatible with a bleeding disorder.

KEY TESTING

• Radiographs should be obtained if a tooth or tooth fragment is missing and thought to be either aspirated, intruded, or lost in the buccal or gingival tissue.

• An initial panoramic radiograph should be obtained if there is a suspicion of mandibular fracture

• A Towne radiograph should be obtained if there is suspicion of a mandibular condyle fracture and the initial panorex is negative or inconclusive.

• CT scanning should be considered if there is suspicion of multiple facial fractures or the panorex is negative and suspicion remains high for mandibular fracture.

• CT or lateral mandibular films can be used to evaluate mandibular injury if the patient is immobilized.

• Bleeding times and coagulation profiles should be considered if the patient exhibits ongoing bleeding and the history is suggestive of anticoagulation or a bleeding disorder.