DEHYDRATION

PHILIP R. SPANDORFER, MD, MSCE

Dehydration is not a disease itself, rather a symptom of another process. Infants have higher morbidity and mortality from dehydration and are more susceptible to it because of their larger water content, three times higher metabolic turnover rate of water than adults, renal immaturity, and inability to meet their own needs independently. Children with various illnesses and circumstances will present to the emergency department (ED) with signs of dehydration (Table 17.1).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Dehydration is a reduction in the water content of the body. Over two-thirds of the total body water is intracellular and one-third is in the extracellular space. Of the extracellular fluid, three-fourths is interstitial and only 25% is in the intravascular space as plasma. Early in the process of dehydration, the majority of the water loss is from the extracellular compartment, which contains 135 mEq per L of sodium and negligible potassium. However, with time, there is an equilibration from the extracellular compartment to the intracellular compartment, which has 150 mEq per L of potassium and negligible sodium. As the electrolyte composition of extracellular fluid and intracellular fluid varies greatly, an understanding of this process helps the clinician gauge the optimal composition and rate of fluid deficit correction (see Chapter 108 Renal and Electrolyte Emergencies).

Dehydration is often categorized by the serum osmolarity and severity (degree of fluid deficit), which is helpful in determining fluid therapy. Based on the initial serum sodium, most children have isonatremic dehydration (also referred to as isotonic dehydration, serum sodium 130 to 150 mEq per L), whereas others have hypernatremic dehydration (hypertonic dehydration, serum sodium greater than 150 mEq per L) or hyponatremic dehydration (hypotonic dehydration, serum sodium less than 130 mEq per L). Severity is judged by the amount of body fluid lost or the percentage of weight loss, and is typically characterized as mild (less than 50 mL per kg, or less than 5% of total body weight), moderate (50 to 100 mL per kg, or 5% to 10% of total body weight), and severe (greater than 100 mL per kg, or greater than 10% of total body weight).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

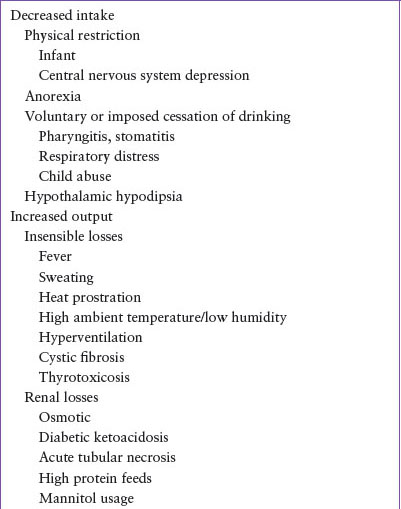

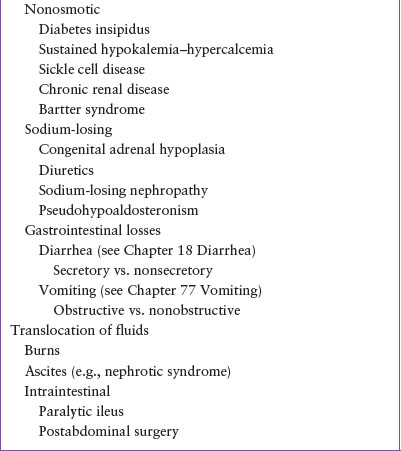

Fluid imbalance in dehydration results from (i) decreased intake; (ii) increased output secondary to insensible, renal, or gastrointestinal (GI) losses; or (iii) translocation of fluid such as occurs with major burns or ascites (Table 17.1). Gastroenteritis is the most common cause of dehydration in infants and children, and is the leading cause of death worldwide in children younger than 4 years of age. In the United States, an average of 300 children younger than 5 years of age die each year, and an additional 200,000 are hospitalized, secondary to diarrheal illnesses with dehydration. Prior to widespread use of the rotavirus vaccine, rotavirus gastroenteritis was responsible for about half of the gastroenteritis cases and is generally more severe than nonrotavirus cases. Other common causes of dehydration in children include vomiting, stomatitis, or pharyngitis with poor intake secondary to pain, febrile illnesses with increased insensible losses and decreased intake, and diabetic ketoacidosis (Table 17.2). More severe or life-threatening causes are listed in Table 17.3.

EVALUATION AND DECISION

The first step in evaluating a child with dehydration is to assess the severity or degree of dehydration, regardless of the cause (Table 17.4). Most children with clinically significant dehydration will have two of the following four clinical findings: (i) capillary refill greater than 2 seconds, (ii) dry mucous membranes, (iii) no tears, and (iv) ill appearance. The more dehydrated a patient is, the more hypovolemic they are and the more likely they are progressing toward shock. Mild, moderate, and severe dehydration correspond to impending, compensated, and uncompensated states of shock, respectively (see Chapter 3 Airway). If there is severe dehydration or uncompensated shock, the child must be treated immediately with isotonic fluids to restore intravascular volume, as detailed later in this chapter.

History

A thorough history is needed to assess the child with dehydration to determine the cause and degree of dehydration (Fig. 17.1). Attention should be paid to the child’s output and intake of fluids and electrolytes. Overt GI losses from diarrhea and vomiting are the most common causes of dehydration in children (see Chapters 18 Diarrhea and 77 Vomiting). The child may not be drinking because of physical restriction (e.g., dependence on a caregiver, pain, altered consciousness, anorexia). Fever, high ambient temperatures or bundling a baby, sweating, and hyperventilation may cause increased insensible losses. It is important to note whether there is any underlying disease that would contribute to dehydration (e.g., cystic fibrosis, diabetes, hyperthyroidism, renal disease).

Asking the parents about documented weight loss, amount of urine output, and the presence or absence of tears is helpful in determining the severity of the dehydration. Although decreased urine output is an early sign of dehydration, only 20% of patients with the complaint of decreased urine output will be dehydrated. All ingested fluids should be noted because diluted juices or water can be associated with hyponatremic dehydration, whereas excess salt intake or low liquid intake may indicate hypernatremic dehydration. Further, inquiring how the infant formula is prepared may lead to the discovery of electrolyte abnormalities with dehydration if too little or too much water is added.

TABLE 17.1

CAUSES OF DEHYDRATION

TABLE 17.2

COMMON CAUSES OF DEHYDRATION

Physical Examination

Vital signs are an important and objective assessment of dehydration (Table 17.4). There are several scoring systems that have been designed to aid in determining the degree of dehydration. A simple 4-point dehydration score that has been shown to be valid and reliable is presented in Table 17.5. The 4-point score is very useful clinically whereas other scoring systems are more useful in research. The first sign of mild dehydration is tachycardia, whereas hypotension is a very late sign of severe dehydration. In mild to moderate dehydration, the respiratory rate is usually normal. As a child becomes more acidotic and fluid is depleted, the respiratory rate increases and the breathing pattern becomes hyperpneic. Unfortunately, vital signs alone are not always reliable. Tachycardia also may be caused by fever, agitation, or pain; respiratory illness affects respiratory rates; and orthostatic signs are difficult to obtain in babies and young children.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree