COUGH

TODD A. FLORIN, MD, MSCE

Cough is a common pediatric complaint with a variety of causes. Although cough is usually a self-limited symptom associated with upper respiratory illnesses, it occasionally indicates a more serious process. Under most circumstances, history and physical examination can accurately determine the cause.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Cough is a reflex designed to clear the airway. Although a cough can be initiated voluntarily, it is usually elicited by stimulation of receptors located throughout the respiratory tract, from the pharynx to the bronchioles, in addition to the paranasal sinuses, stomach, and external auditory canal. Receptors may be triggered by inflammatory, chemical, mechanical, and thermal stimuli. Direct (central) stimulation of a cough center in the brain occurs more rarely. The reflex consists of a forced expiration and sudden opening of the glottis, which rapidly forces air through the airway to expel any mucus or foreign material.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

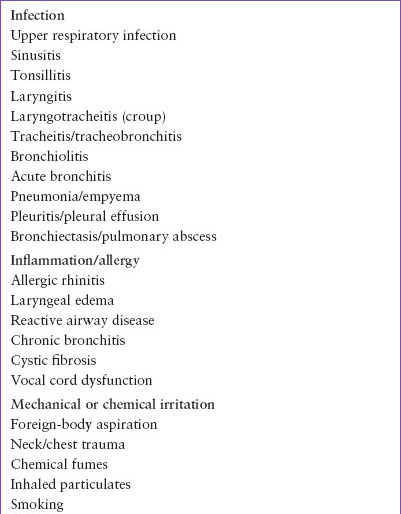

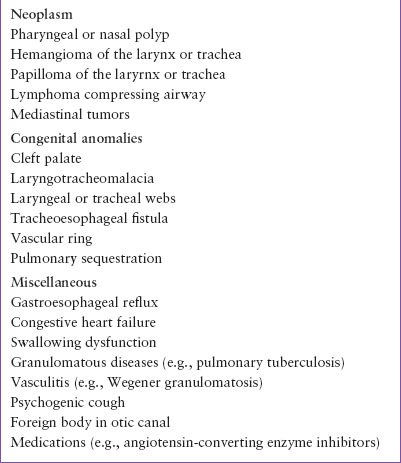

The causes of cough differ in the type of stimulus and the site of involvement in the respiratory tract (Table 14.1). The common causes of cough are listed in Table 14.2. Potentially life-threatening causes are listed in Table 14.3.

In distinguishing the etiologies of cough, the clinician must consider features that are atypical for simple upper respiratory infections (URIs) or routine asthma. Although pertussis exists as a URI in the catarrhal phase, infants with paroxysms of coughing, color change, significant posttussive emesis, or apneic episodes should be tested and managed as possible pertussis. Similarly, toddlers and young children with new-onset wheezing following a choking episode, those infants with wheezing unresponsive to usual therapy, and those with persistent lobar pneumonia should be evaluated for a foreign body. Cough associated with expectoration of blood (hemoptysis) should prompt evaluation for infection, vasculitis, pulmonary vascular disorders, trauma, congenital heart defects, neoplasm, or coagulopathy. Finally, children who present with cough and associated stridor may have croup, but those with recurrent stridor, associated dysphagia, or chronic hoarseness must be evaluated for a foreign body, extrinsic compression of the trachea (vascular ring, tumor), or laryngeal pathology (papilloma, hemangioma).

EVALUATION AND DECISION

The history and physical examination are the keys to establishing a diagnosis in a patient with cough. The first priority is to recognize and treat any life-threatening conditions. Patients with significant respiratory distress should receive supplemental oxygen and rapid assessment of their airway and breathing (Fig. 14.1).

History

Cough can occur as an acute or chronic symptom, depending on the underlying process. Most common and serious causes of cough have an acute onset (Fig. 14.1). Certain conditions, such as asthma, may present with an acute or a chronic history of cough.

The relationship of the cough to other factors is helpful. Cough in the neonate must raise the possibility of congenital anomalies, gastroesophageal reflux, congestive heart failure, and atypical pneumonia (e.g., Chlamydia). If the cough began with other upper respiratory tract symptoms or fever, an infectious cause is likely. A cough that started with a choking or gagging episode, especially in an older infant or toddler, suggests a foreign-body aspiration (see Chapter 27 Foreign Body: Ingestion and Aspiration). Concern for button battery and peanut aspirations require emergent evaluation and removal when present. Cough associated with exercise or cold exposure, even in the absence of wheezing, may be a sign of reactive airway disease. A primarily nocturnal cough often stems from allergy, sinusitis, or reactive airway disease. Systemic complaints should also be considered in patients with a cough: Headache, fever, facial pain or pressure (sinusitis), acute dyspnea (asthma, pneumonia, cardiac disease), chest pain (asthma, pleuritis, pneumonia), dysphagia (esophageal or pharyngeal foreign body), dysphonia (laryngeal edema or tracheal mass), or weight loss (malignancy or tuberculosis).

The quality of the cough may also be helpful in determining etiology. A barking, seal-like cough, with or without stridor, supports the diagnosis of laryngotracheitis (croup). A paroxysmal cough associated with an inspiratory “whoop,” cyanosis, or apnea is characteristic of pertussis. Infants younger than 6 months of age with pertussis may present with severe cough, poor feeding, apnea, or bradycardia without the classic whooping paroxysms of cough. Tracheitis gives a deep “brassy” cough, whereas conditions accompanied by wheezing (asthma or bronchiolitis) typically produce a high-pitched “tight” (often termed bronchospastic) cough. Vocal cord dysfunction can result in cough and audible wheeze that may mimic asthma, and should be considered in older children and adolescents with multiple cough and wheezing episodes that do not respond to repeated courses of standard asthma therapy. Determining whether a cough is productive can be difficult in young children who often swallow, rather than expectorate, their sputum. Although a productive-sounding cough may be seen with uncomplicated URIs, sinusitis and lower respiratory tract infections are more commonly accompanied by a productive cough. Contrary to popular belief, the color of expectorated sputum does not necessarily indicate infectious or bacterial etiology.

TABLE 14.1

CAUSES OF COUGH IN CHILDREN

Typically, the onset of cough with rhinorrhea suggests a viral URI or bronchiolitis. However, if a child with an apparent URI becomes more ill or has persistent symptoms, secondary bacterial infections in the lungs or sinuses, pertussis, as well as noninfectious etiologies should be considered.

TABLE 14.2

COMMON CAUSES OF COUGH

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree