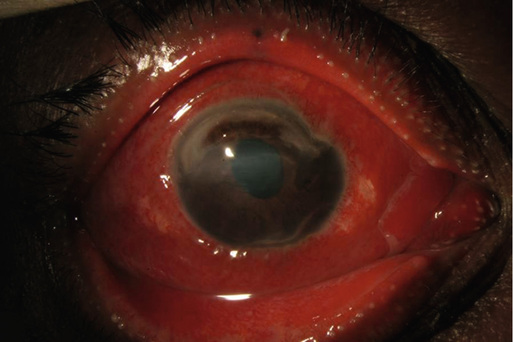

Sarah P. Read, James T. Banta Conjunctivitis is inflammation of the bulbar or palpebral conjunctiva, the transparent mucosal tissue that lines the eye and inner surface of the eyelids.1 Approximately 70% of patients with acute conjunctivitis visit a primary care provider for diagnosis and management.1,2 Commonly referred to as pink eye, conjunctivitis actually consists of many different disorders. Infectious causes include viruses and bacteria. Noninfectious conjunctivitis can commonly be caused by allergy, atopy, or exposure to toxins.2 Up to 70% of all infectious conjunctivitis is viral.1 The most common causative organism is adenovirus, the same virus implicated in the common cold.3 Bacterial conjunctivitis is the second most common cause of infectious conjunctivitis and the most common cause in the pediatric population.4 Other infectious causes include virus infections such as herpes and molluscum contagiosum. The most common cause of noninfectious conjunctivitis is allergic conjunctivitis, a condition seen most frequently in the spring and summer.5 Approximately 15% of all eye-related complaints to a primary care provider are secondary to allergic conjunctivitis.6 Other noninfectious causes include primary ocular diseases such as toxic or cicatricial conjunctivitis and systemic diseases such as graft-versus-host disease, systemic inflammatory disorders, or neoplastic processes.7 Viral conjunctivitis is spread by direct contact or by proximity to an infected patient.8 Because of its highly contagious nature, viral conjunctivitis is often seen in areas of overcrowding, such as schools, nursing homes, and summer camps.1,9 Similarly, bacterial overgrowth in the conjunctiva occurs directly from hand-eye contact with an infected individual or from the transfer of organisms in one’s own nasal and sinus mucosa.1 Commonly known as hay fever, seasonal allergic conjunctivitis is typically secondary to environmental allergens, with ragweed being the most common (75%).6,10 Perennial allergic conjunctivitis is caused by common household allergens such as household chemicals or pet dander. In both conditions, an inflammatory response occurs once the airborne allergen comes into contact with the ocular surface.9 Acute allergic conjunctivitis is characterized by an immunoglobulin E mast cell–mediated hypersensitivity.6 Vernal conjunctivitis and atopic conjunctivitis are chronic, mast cell–and lymphocyte-mediated immune processes. Both are considered to be more severe and chronic forms of allergic conjunctivitis.10 Environmental allergens can trigger exacerbations.7,10 Conjunctivitis from a medication typically occurs with long-term use (>1 month) of an eye drop.9 Any eye drop can be causative, but conjunctivitis is most commonly encountered with eye drops containing the preservative benzalkonium chloride (listed as an inactive ingredient). It can also be seen as a response to excessive use of a vasoconstrictor (e.g., naphazoline, tetrahydrozoline). Vasoconstrictors are excellent at removal of redness acutely, but if they are used for longer than 3 to 5 days, rebound vasodilation is frequently encountered. This may take as long as 4 weeks to resolve fully.9 The use of vasoconstrictors should be uniformly discouraged except for infrequent, intermittent use. Other common causes of medication toxicity include topical antibiotics, especially aminoglycosides, and glaucoma medications.9 Evaluation of a patient with conjunctivitis should first start with a careful history. A recent upper respiratory infection or exposure to sick individuals can point to a diagnosis of adenoviral conjunctivitis.1,11 Ocular symptoms include acute onset of a red eye with excessive watery discharge.2 Classically, it begins in one eye and then involves the fellow eye within days due to the phenomenon of autoinnoculation.11 Approximately half of patients will have bilateral involvement at the time of presentation.11 Adenoviral conjunctivitis can occur in three different forms.2,9 On examination, the lower eyelid should be pulled down and the palpebral conjunctiva evaluated. Follicles are clear bumps, ranging in size from pinpoint to 2 mm, with overlying conjunctival vessels (Fig. 73-1).7,9 The second form is pharyngoconjunctival fever. The ocular examination is similar. However, the patient will have systemic disease: fever, headache, and sore throat.2 Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis is clinically striking with significant, bilateral conjunctival hyperemia and chemosis. Petechial and larger subconjunctival hemorrhages may be present in this form.1,9 Up to one third of patients with epidemic keratoconjunctivitis have corneal involvement, and it is appropriate to refer these patients to an ophthalmologist.12 When a patient with suspected adenoviral conjunctivitis is examined, it is important to palpate the anterior cervical chain of lymph nodes. At least 50% of patients have a tender preauricular lymph node.2 The preauricular node is located just inferior and medial to the tragus. Of note, certain types of bacterial conjunctivitis can also manifest with lymphadenopathy (specifically, Neisseria- and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA]–associated bacterial conjunctivitis).1 Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection accounts for 1.3% to 4.8% of acute conjunctivitis.2 It can be spread by direct contact but is more commonly spread by asymptomatic shedding of viral particles. Children with primary HSV infection will often have an antecedent respiratory infection. The disease is almost always unilateral and can cause concurrent vesicular skin lesions.2 Recurrent HSV infection can manifest similarly but often involves other ocular structures. Therefore in patients with a history of prior cold sores and with presumed herpetic eye disease, referral to an ophthalmologist is recommended.1,9 Molluscum contagiosum is spread by direct contact. Because it typically occurs in children, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection should be considered if it is seen in adults.1,9 Patients have a chronic follicular reaction. On examination of the eyelid margin, an umbilicated nodule is characteristic. Referral to an ophthalmologist should be made for evaluation and potential excision.9 Bacterial conjunctivitis is typically accompanied by thick, purulent discharge.11 On history, patients will often report that both eyes are sticky or glued shut. These symptoms persist throughout the day but are worse in the morning.13 Bacterial conjunctivitis can result from the overproliferation of native ocular flora or from direct spread from an infected individual.2 Acute conjunctivitis is the most common form of bacterial conjunctivitis. Symptoms manifest over days. In children, the causative agents include Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae. S. aureus is more commonly seen in adults.8,13 Symptoms typically last for 7 to 10 days.2 Hyperacute onset (12 to 24 hours) with severe purulent discharge is highly consistent with Neisseria gonorrhoeae.9,13 Gonococcal conjunctivitis is typically seen in sexually active adults but can also occur in neonates via maternal-neonate transmission.9,13 If it is seen in a child, child abuse should be suspected. Rapid progression is the hallmark of this disease. The cornea can become involved in less than 2 days and lead to permanent vision loss (Fig. 73-2).9

Conjunctivitis

Definition

Epidemiology

Pathophysiology

Clinical Presentation and Physical Examination

Viral Conjunctivitis

Bacterial Conjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis

Chapter 73