CHAPTER 39 COMPLICATIONS OF PULMONARY AND PLEURAL INJURY

It has been stated that chest trauma is the primary cause of death in up to 25% of fatalities following traumatic injury, and a major contributing factor in another 25%, although as few as 5%–15% require acute operative intervention. Based on these generalizations, it is accepted that overall chest injury is common, acute operative intervention uncommon, and a significant, although ill-defined, number of thoracic operations are performed for delayed complications. The actual incidence of each of these varies from center to center based on ratio of blunt to penetrating admissions as well as overall volume. The two most common complications, persistent air leak and empyema, occur roughly in 5% of patients admitted who have required tube thoracostomy.

PULMONARY

Persistent Air Leak

Persistent air leak in a ventilated patient without a discrete lesion is better thought of as an alveolar-pleural fistula rather than a BPF. Clearly, the underlying lung injury affects outcome, with alveolar-pleural leak in adult respiratory distress syndrome patients being associated with up to 80% mortality. Whatever the underlying anatomy, air leak in ventilated patients can be a significant marker of increased mortality. Pierson and colleagues reviewed the course of 39 patients (out of a population of 1700 mechanically ventilated patients) who presented with air leak lasting more than 24 hours, of whom 27 were trauma patients. The risk factors for mortality correlated with the following: air leak not present on admission or shortly thereafter (45% early vs. 94% if developed later); leak greater than 500 ml per breath (57% if less vs. 100% if greater); and post–chest trauma (56% for trauma admissions vs. 92% for nontrauma admissions). These findings illustrate that while the course in trauma admissions is more benign, it still represents a major concern. On the other hand, the air leak itself is rarely the cause of death. These air leaks can lead to persistent or even tension pneumothorax that compromises ventilation. Pleural tubes (at times multiple) may be required. Less commonly, air leak is significant enough to affect oxygenation. The primary treatment is to minimize alveolar pressure, using end-inspiratory plateau pressure as an (admittedly crude) reflection of this. Ideally, the end-inspiratory plateau pressure should be less than 30 cm H2O. The most common method of attaining this is to combine low tidal volume and permissive hypercapnia. Alternative methods if this approach fails are high-frequency jet ventilation or independent lung ventilation. It should be stressed that high-frequency jet ventilation, although used successfully in patients with central airway disruption and in the operating room, does not reduce mean airway pressure consistently, nor does it uniformly reduce air leak or improve oxygenation. Thus, it should not be used routinely in patients with alveolar-pleural fistula. A temporizing technique is to isolate the lobe that is the primary source of leak bronchoscopically. This is done by sequentially occluding bronchi with a Swan-Ganz or other balloon catheter. If this results in elimination or significant reduction in air leak, occlusive material (Gelfoam, fibrin glue, blood mixed with tetracycline, etc.) can be injected. In most cases, the air leak will diminish as airway pressure decreases. Surgery can be performed, but in the setting of diffuse parenchyma injury, lung inflammation, severe emphysema, and/or steroids, the risk is that staple lines will fail and the leak will be exacerbated. If surgery is felt to be needed, reinforced staple lines (i.e., with bovine strips, etc.), apical tents (mobilizing the apical pleura so that it falls onto the area of resection), and/or anatomic lobectomy (if predominantly one lobe) should be considered.

Pneumonia

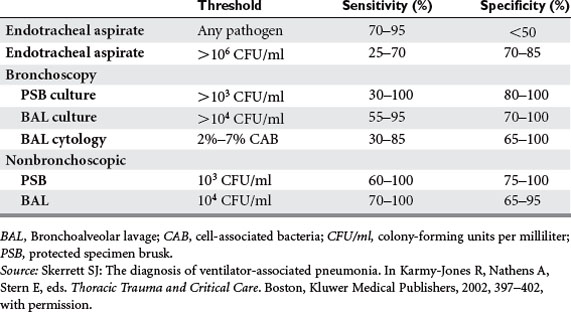

Pneumonia may be the most common complication of chest trauma. Risk factors include aspiration, need for ventilation, direct injury, pulmonary contusion, and persistent atelectasis secondary to pain. The incidence is as low as 6% in nonintubated patients to as high as 44% in ventilated patients. Despite the high incidence, there are no data supporting prophylactic antibiotics. Of all patients admitted with a diagnosis of pulmonary contusion, nearly 50% will develop pneumonia, barotrauma, and/or major atelectasis. One-fourth will progress to adult respiratory distress syndrome. Ventilatorassociated pneumonia (VAP), defined as pneumonia arising more than 48 hours after initiation of mechanical ventilation, is difficult to define and diagnose. At our institution, we have found that the incidence in patients ventilated for more than 7 days ranges from 20% to 30%. Clinical suspicion is often raised by new infiltrates, recurring fever, rising leukocytes, and/or a change in endotracheal secretions. However, distinguishing between colonization and infection may require specialized techniques. Quantitative cultures obtained from a variety of approaches increase the specificity (although perhaps with reduced sensitivity) of endobronchial cultures, and each institution must define cut-off values based on whether the patient is already receiving antibiotics (Table 1).

Necrotizing Lung Infection

The cause(s) of lung abscess in the surgical intensive care unit (ICU) population include aspiration, complications of pneumonia, retained foreign body, septic emboli, and/or infected traumatic injury. More specific etiologies in the trauma population include aspiration (with or without bronchial obstruction), infected pneumatocoele, infected site of resection (in particular emergent tractotomy), and late complications of ventilatorassociated pneumonia. As a whole, these are less common in trauma patients than nontrauma patients. Of 45 thoracotomies performed at our institution over 7 years for abscess, necrotizing pneumonia, and lung gangrene, only 4 were in patients initially admitted after traumatic injury.

Over the three decades of approximately the 1950s through the 1970s, a number of advances reduced the mortality rates from approximately 50% to 10%. These advances included recognizing the importance of antibiotics, the role of aspiration, the need for pulmonary toilet (including liberal use of bronchoscopy), and finally the benefit in selected patients of operative intervention. Subsequently, the major addition to the armamentarium has been image-guided catheter drainage as an intermediate category between medical and surgical management. Percutaneous catheter drainage can be performed even in ventilated patients and has reduced the number of thoracotomies required. While there is always concern about the risk of empyema and/or bronchopleural fistula, the former can be usually easily managed by chest drainage, and the latter is rarely so significant as to impair oxygenation. Some patients will require thoracotomy, which, in the trauma population, usually results from persistent sepsis and inability or incomplete drainage, hemoptysis, or persistent or major bronchopleural fistula (see Table 1). The two primary operations are lobectomy for large central cavities, or debridement (plus muscle flap to help close the space) for smaller peripheral cavities. At operation, there are several technical points that can help reduce complications: prevent aspiration by isolating the affected lung before posterolateral positioning; expose the main pulmonary artery early in the case so that control can be achieved should hemorrhage result; place a nasogastric tube or esophagoscope in the esophagus because the anatomy may be obliterated; and refrain from resecting small abscesses (<2 cm) that are in otherwise viable parenchyma. Air leak is not uncommon, and, as will be discussed under the empyema section, a residual space can be managed with continuous postoperative irrigation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree