TRACHEOSTOMY TUBES AND CANNULAS

A tracheostomy is an opening between cartilaginous rings in the trachea and the skin, with a tracheostomy tube placed into the stoma to facilitate ventilation. Tracheostomy is usually performed by an otolaryngologist as an elective or semi-elective procedure and is not an emergency procedure. Most tracheostomies are performed on chronically ill patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation.

There are many types of tracheostomy tubes available, including those made of plastic, silicone, nylon, and metal. Most hospitals stock only a few types of tracheostomy tubes, and one must be familiar with the types available. Tracheostomy tubes vary in diameter, total length, the length before and after the curve, and the presence or absence of a cuff (Figure 247-1). The size of the tracheostomy tube is usually defined by the inner diameter, ranging in adults from 5 to 10 mm and in pediatric patients from 2.5 to 6.5 mm. Most pediatric and adult tracheostomy tubes have a 15-mm standard respiratory connection that may be used with ventilator tubing or a bag-valve device.

Fenestrated tracheostomy tubes have an opening along the dorsal surface of the body of the tube. The fenestration allows the passage of air through the tracheostomy tube to the vocal cords so the patient can speak. Irritation from the fenestration may promote growth of granulation tissue, which may extend into the fenestration, leading to bleeding, obstruction, and difficulty removing the tracheostomy tube. If any difficulty is encountered removing a fenestrated tracheostomy tube, obtain surgical or ear, nose, and throat consultation.

Most adult tracheostomy tubes have a removable inner cannula, which allows secretions to be cleared from the lumen without removing the entire tube from the trachea. In assessing an adult tracheostomy patient, remove and examine the inner cannula for crusting or obstruction. Both disposable and reusable inner cannulas may be cleaned by using a small brush dipped in a solution of hydrogen peroxide and then rinsing the cannula with warm tap water. If the correct size of disposable inner cannula is not available in the ED, use the existing inner cannula temporarily, or change the entire tracheostomy tube. Pediatric tracheostomy tubes never have an inner cannula because of the small inner diameter, so the entire tube must be removed for cleaning.

Complications due to the surgery are grouped according to the timing since the tracheostomy and the technique. Summed complication rates from randomized controlled trials show 10.0% for percutaneous technique and 8.7% for open tracheostomy.1 Bleeding, obstruction, dislodgement, and infection are all potential early complications, occurring within the first week. Late complications are those that occur after 1 week. Granulation, tracheal stenosis, a fistula (tracheocutaneous, tracheoesophageal, or tracheoinnominate) plus any of the early complications may be late complications.1,2,3,4 Risk factors for tracheal stenosis are intubation duration of more than 1 week and having an endotracheal tube larger than 7.5 mm.4

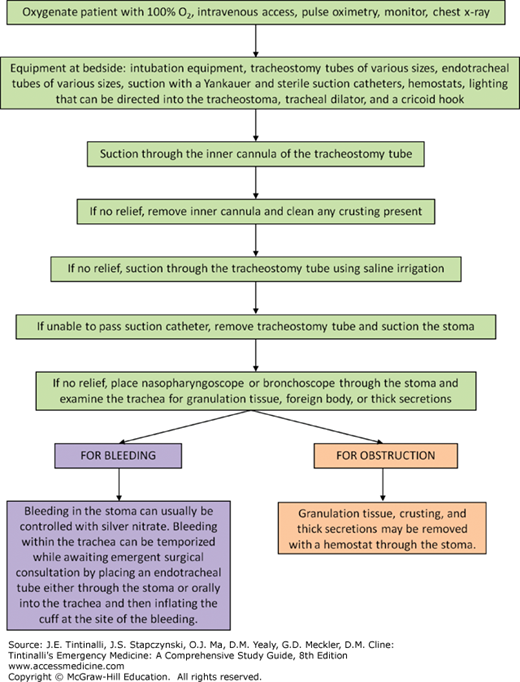

Patients with tracheostomy tubes can develop respiratory distress. Figure 247-2 is a step-by-step approach to assess and treat respiratory distress. In the ED, the provider must be proficient in the following skills (as outlined in the sections that follow): replacement of an uncuffed with a cuffed tracheostomy tube for mechanical ventilation, replacement of a tracheostomy tube after accidental decannulation, correction of a tube obstruction, and control of bleeding or infection at the tracheostomy site. It is important to determine a few key elements about the tracheostomy: when and why was the procedure performed, what type of tracheostomy tube is the patient using currently, and can the patient be orally intubated if needed? Patients who have undergone a laryngectomy or who have tumors or scarring that occlude the upper airway cannot be orally intubated.

Consider mucus plugging of the trachea or mainstem bronchi distal to the tube. If the tracheostomy is patent and is in the airway, leave it in place. If the tracheostomy tube is obstructed, mucous plugging is commonly the cause. Secretions may act as a ball-valve mechanism, allowing air in but restricting exhalation. Suctioning may relieve the obstruction. Preoxygenation and placement of sterile saline solution into the trachea will aid in suctioning. Prolonged use of large suction catheters without preoxygenation will cause hypoxemia. If mucous plugging cannot be relieved by suctioning, the inner cannula of the tracheostomy tube and, occasionally, the entire tracheostomy tube may need to be removed and cleaned.

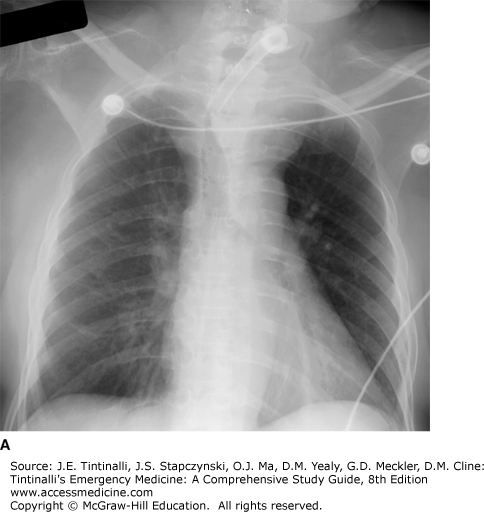

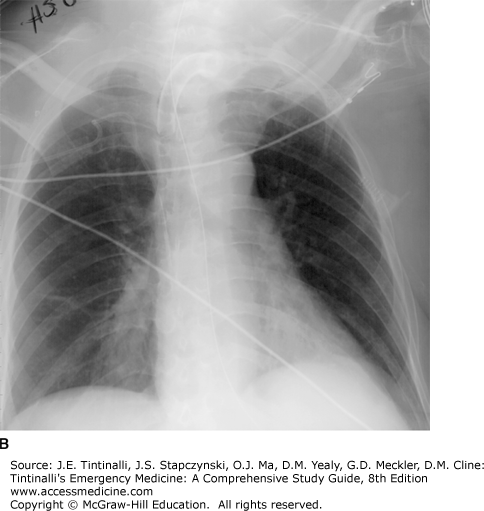

It is possible for the tracheostomy tube to become dislodged from the trachea but still be in the neck. In this case, a suction catheter cannot be passed through the tube, and on x-ray, the tracheostomy tube may be seen to extrinsically compress the trachea (Figure 247-3). In this circumstance, remove the entire tracheostomy tube. It may be difficult to accurately identify the actual tracheal stoma when replacing the tube (see “Changing a Tracheostomy Tube” section below). A nasopharyngoscope or flexible bronchoscope should be inserted into the visible stoma in an attempt to identify the tracheal opening. If the opening still cannot be identified, obtain ear, nose, and throat or surgical consultation. If the patient cannot maintain the airway, oral intubation will be necessary.

Indwelling tracheostomy tubes are contaminated with normal or pathogenic flora. Surgical site infection is more common in patient post open tracheostomy (7%) than percutaneous insertion (3.4%).5 Stomal skin infection, tracheitis, and bronchitis can be a recurring problem. Infection may be polymicrobial, including Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas, and Candida. Antibiotics are indicated in the setting of clinical disease. STable patients can be treated with amoxicillin-clavulanate, 875 milligrams PO twice daily.6 UnsTable patient should receive piperacillin-tazobactam, 3.375 grams IV, plus vancomycin, 1000 milligrams IV. Use a fluoroquinolone for Pseudomonas. Dressing changes with gauze soaked in 0.25% acetic acid are effective for local wound infections.

Bleeding can occur at any time after a tracheostomy. Granulation tissue in the stoma, trachea, or thyroid or erosion of the thyroid vessels, the tracheal wall (frequently from suction trauma), or the innominate artery are all sources of hemorrhage. Slow bleeding originating from the stoma may be controlled by packing the site with saline-soaked gauze. If this is ineffective, remove the tube and examine the stoma and tracheal wall. Local bleeding can be controlled with silver nitrate. Electrocautery should be done by a surgeon. If bleeding is brisk, replace the tracheostomy tube with a cuffed endotracheal tube with the cuff below the bleeding site.

Tracheoinnominate artery fistula is a rare but life-threatening complication of tracheostomy. Cuff pressure >25 mm Hg, tracheostomy below the third tracheal ring, and deformed neck or chest are all risk factors.7 Bleeding results from vessel erosion caused by either direct pressure of the tip of the tracheal cannula against the innominate artery or from a cuff with inappropriately high pressures due to overinflation. Most patients with a tracheoinnominate artery fistula present within the first 3 weeks after tracheostomy, with the peak incidence between the first and second week. Some patients may have a sentinel arterial bleed or hemoptysis. Bleeding may be mild or severe and should be thoroughly investigated because of the potential for sudden massive hemorrhage.8 Immediate otolaryngologic and thoracic surgery consultation is required, and operative repair is lifesaving.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree