Chapter 15

Complementary therapy approaches to pain

Popularity of complementary and alternative medicine

Working with the whole person in pain

Psychoneuroimmunology, imagery and pain

Touch: a tool for acknowledging and relieving distress and pain

Specific patient-focused therapies

The pain of loss: caring for carers

Recommendation for best practice in delivering complementary therapies

The objectives of this chapter are:

1 To develop the reader’s understanding of the role and limitations of complementary therapies in pain management.

2 To consider the evidence base for specific complementary therapies interventions for patients living with pain.

3 To explore key practical and professional issues in the integration of complementary therapies within clinical practice.

4 To identify possible sources of information and guidance to help increase the reader’s knowledge and awareness of this area of work.

POPULARITY OF COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE

CAM is used globally, with different practices reflecting local cultural health beliefs and values. Internationally, training varies enormously from skills passed on amongst communities to formalized accredited programmes within colleges and university settings. The attitudes of the medical establishment are changing from dismissal of CAM to demands for greater regulation and evidence of safety and efficacy to support further integration. Surveys conducted in the UK and Australia indicate that 25–50% of the general population use CAM on a regular basis, often at their own expense (Ernst & White 2000; Thomas et al 2001). Complementary therapies popular with patients in the UK include aromatherapy, massage, medical acupuncture (discussed in Chapter 14), reflexology, creative imagery and relaxation; these lend themselves to greater integration within mainstream health care. Alternative disciplines, such as herbal medicines, homeopathy, traditional Chinese medicine, reiki and spiritual healing, are more common in private practice settings, with some limited access in publically funded healthcare services. This chapter focuses on the use of complementary therapies (CTs).

The term ‘complementary’ encompasses a wide range of treatments and products. National guidelines for the use of CTs in supportive and palliative care uses the term to broadly describe therapies used alongside conventional health care (Tavares 2003). Stone (2001) suggests that in both the UK and the USA there has been a significant shift towards ‘integrated or integrative health care’ (p. 55) and greater tolerance towards the inclusion of CTs within private and public healthcare services. The Foundation of Integrated Medicine’s discussion document on integrated healthcare (Foundation for Integrated Medicine 1997), established by HRH the Prince of Wales, examined practical ways in which conventional and complementary therapists could develop a working partnership. Over a decade later, challenges with funding and the building of an evidence base still continue to be issues for this integrative movement that prevent widespread provision of CTs to patients within the NHS. Pockets of good practice do exist, although these are often highly dependent on committed practitioners, support from clinical champions and access to charitable funds.

Resistance to greater integration of CTs comes from conventional practitioners who question their efficacy and validity, particularly where there is a cost to the service provider and/or the patient. Because of the term ‘CAM’, CTs are often linked to the use of ‘alternative’ therapies by patients and concerns that they will abandon recommended (and evidence-based) conventional medicine, with potential consequences for disease progression and/or other harmful consequences. Cassileth et al (2001) suggest that ‘alternative therapies’ may be defined as unproven treatments promoted to treat the disease itself, whereas ‘complementary therapies’ represent adjunctive therapies aimed at symptom management and enhancement of quality of life. Swisher et al (2002) claim that most patients who use alternative therapies do so in conjunction with standard medical therapy, with only a small minority choosing alternative therapy to the exclusion of standard medical treatment. The recommendations and therapeutic practices discussed in this chapter focus on the best of CTs working in conjunction with high-quality conventional medicine, equally alternative therapies are NOT recommended as curative modalities by the authors. Importantly, it is advised that within practice settings the CTs used with patients and carers are:

1. delivered by appropriately trained, supervised and insured practitioners

2. adapted skilfully for the individual, who is informed and has consented for the intervention offered

3. provided by practitioners who work in collaboration with conventional health professionals to deliver high-quality, accountable and evaluated care

4. most importantly: when there any concerns about safety or risks of harm to the patient, the interventions are not offered.

REASONS FOR USING CTs

When reviewing the literature, multiple reasons are given for the tremendous use of CTs amongst patients who have cancer and long-term conditions. Cassileth (1998) suggests that CAM is used for a variety of reasons ranging from supporting patients’ psychological needs to dissatisfaction with the medical system and/or the nature of the relationship with the physician. Coss et al (1998) undertook a telephone survey of cancer patients (n = 503) in California. They suggest that people turn to CAM for the following reasons: a desire to be treated as a whole person, to be able to participate in his or her own care and through a sense that traditional medicine has failed to meet their spiritual or psychological needs.

WORKING WITH THE WHOLE PERSON IN PAIN

Bollentino (2001, p. 101) reminds us ‘each person is an organic whole, with inseparable physical, intellectual, psychological, social, creative, and spiritual aspects.’ Working holistically acknowledges the uniqueness of the individual and his or her response to pain. Meeting the whole person requires the development of the therapeutic relationship, well recognized within the field of health care and CAM. Erskine et al (1999) recommend that this relationship should be nurtured and entered into fully for its potential for psychological well-being. Clarkson (1992) takes this further by referring to working at the transpersonal relationship level with people facing challenging symptoms and life-threatening illness.

Relationships develop between people and within a certain environment – a ‘therapeutic space’ can be created anywhere, even in a busy ward or clinic. Creating and maintaining this ‘special space’ allows us to go beyond the physical. Bion (1962) uses the term ‘containment’ to encompass ‘being there’ and ‘attuning’ with another in their pain and suffering. Importantly, this includes an ability to both witness and ‘hold’ any emotional material that might arise. A patient will only feel safe if he or she knows that the practitioner will not be overwhelmed by it. Viewing pain in the physical domain alone ignores the potential of engaging the patient and with his or her own resources and capacities, be they spiritual, psychological and/or social.

PSYCHONEUROIMMUNOLOGY, IMAGERY AND PAIN

The use of imagery has developed in the field of cancer care and is part of the growing field of psychoneuroimmunology (PNI). The connection between the immune system and imagery has been studied in some depth. There is now enough evidence on the mind (psychology), the brain (neurology) and the body’s natural defences (immunology) to suggest that the mind and body communicate with each other (Ader 1996; Evans et al 2000). This has been made possible through a rapid advance in scientific understanding of the immune system over the past 30 years. Watkins (1997) asserts that PNI research has generated hard scientific data that provide irrefutable evidence that virtually all the body’s defence systems are under the control of the central nervous system. This research was the beginning of more extensive research on the mind–body connection.

The concept that every thought, idea and belief is part of the mind–body pathways raises interesting questions into the role of these in maintaining health and fighting disease. Although much of this work is in its infancy, the potential for its use is proving to be an exciting area. Simonton et al (1980) pioneered the use of imagery to treat cancer patients with advanced disease. Their study involved 225 participants where imagery was used in combination with traditional medical treatment. The imagery involved encouraging patients to imagine and draw their cancer, immune defences and medical treatments. The aim of this approach was for the patients to see the disease as weak and the host resistance and treatment as strong and therefore more likely to overcome the disease. The findings demonstrated that the median survival time of the clients in the experimental group was 18–19 months longer than the national average for persons with breast, bowel and lung cancer. However, there has been much debate over the findings of this particular study and other similar ones. Cunningham (2000) questions whether it is the technique which can heal, or whether the positive outcome is due to the patient gaining a sense of control. Further research is required to test these hypotheses.

A study described by Giedt (1997) suggests how the use of guided imagery as a nursing intervention using psychoneuroimmunology (PNI) principles can assist in the management of distressing symptoms such as pain, which is a common problem associated with cancer. Giedt (1997) states that pain causes both a physical sensation and a mental image, so paying attention to the metaphors used by the patient to describe the pain sensation may have an effect on the pain.

Imagery is potentially important in healing because it may in some circumstances act as a blueprint or set of instructions to the body, as an intermediary between thoughts and physiological changes. For example, fearful images can stimulate the stress response (Cunningham 2000). Davis-Brigham et al (1996) suggest that imagery goes on at all times in all individuals, both at a conscious and unconscious (and maybe even cellular) level. They suggest that when assessing a patient’s suitability for imagery, an important starting point would be to explore the imagery already in place in relation to disease, health, values, fears and what the person sees as occurring in the body. They recommend that any guided imagery must be syntonic with the individual’s core beliefs. It needs to fit in with their deepest values and not be contradictory with their view of the world. An example would be to avoid aggressive imagery, such as attacking the cancer, when a more gentle approach would better suit the individual.

PLACEBO, NOCEBO AND PAIN

Hope can have powerful effects on the experience of a symptom such as pain and can be linked to the concept of placebo: an inert substance or supposedly ineffective treatment may result in a perceived or physiological improvement in symptoms. This is called the placebo effect (Benedetti 2009). The phenomenon is related to the patient’s expectation; if the substance is viewed as helpful, it can help, but if it is viewed as harmful, it can cause negative effects. This is known as the nocebo effect.

Originally, the term ‘placebo’ was attributed to benefits from ‘pleasing the patient’ rather than as a result of the intervention itself (Beecher 1955). Expectation of outcome is argued to be a key component of placebo, with signals such as the colour, shape and name of a pill being significant. Importantly, confidence in who prescribes and what is said about the intervention can also influence perception of the potency of the treatment (Kienle & Kiene 1997). Other important interactive components between a therapist and a client which may be influenced by the placebo/nocebo effect include the patient’s ability to manage or contain anxiety, the therapeutic relationship itself and the characteristics of the practitioner. Important here is the language, non-verbal cues and paralinguistic components of the practitioner–patient interaction. For example, if the practitioner is hesitant, does not maintain good eye contact and infers by speech that the intervention ‘might help’ (i.e. ‘may not’), the patient may be less than confident about the therapeutic benefits. There is a delicate balance to be struck between inspiring confidence and being realistic. Highly anxious patients may worry about side effects or have high expectations of not responding well to the treatment (Box 15.1).

TOUCH: A TOOL FOR ACKNOWLEDGING AND RELIEVING DISTRESS AND PAIN

The therapeutic use of touch by nurses and other health professionals has been well discussed in the literature, with acknowledgment that we touch patients for a variety of reasons, such as washing, applying dressings and holding during medical procedures. Intention is a key issue in relation to touch and in the past healthcare practice has been criticized for being largely task orientated in touching behaviours. Supportive empathic touch works on a physical and intuitive level and provides comfort that is a physical expression of ‘being there and with the patient’. Provided with openness and sensitivity, another person’s touch can be profound in its humanizing effects and is often moving for both the patient and the practitioner. If overburdened and time deprived, health professionals may avoid this intimate act, unsure of their capacity to be in the moment and open to being really present with another person, particularly if their distress is palpable. They may additionally feel unsure of their ability to manage any emotional responses from the patient which occur as a result of the encounter. Equally, a patient may not always welcome the therapeutic use of touch, however well intentioned. Closing down to physical touch can occur when an individual feels their body has become a painful battleground invaded by investigations, medical devices and treatments. Touch history is important, and sometimes painful and/or abusive touch experiences may have shaped how receptive a person is to physical contact. Receptivity and appropriateness can only be assessed by viewing touch as a negotiated activity, with the patient able and fully aware that they can say ‘no’ at any point. This golden rule, which respects autonomy, Mackereth (2000) argues should apply to any therapeutic or clinical activity involving touch.

SPECIFIC PATIENT-FOCUSED THERAPIES

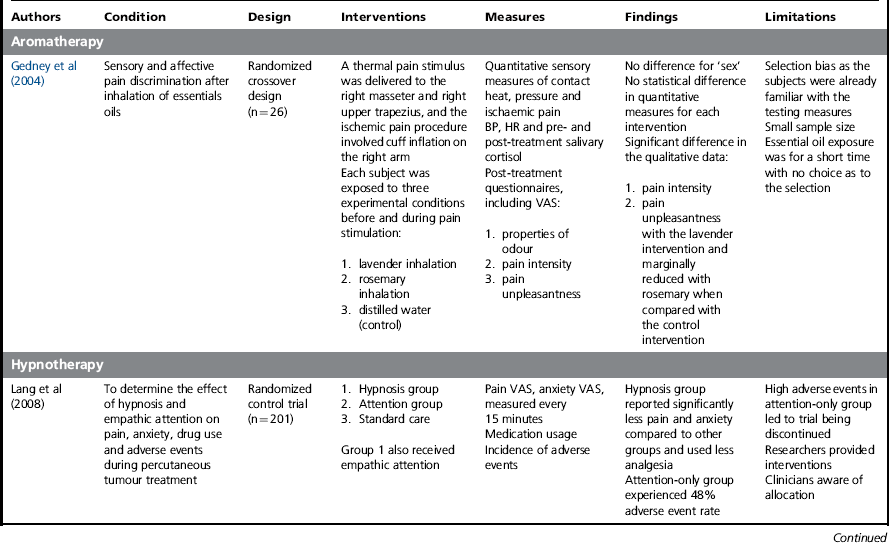

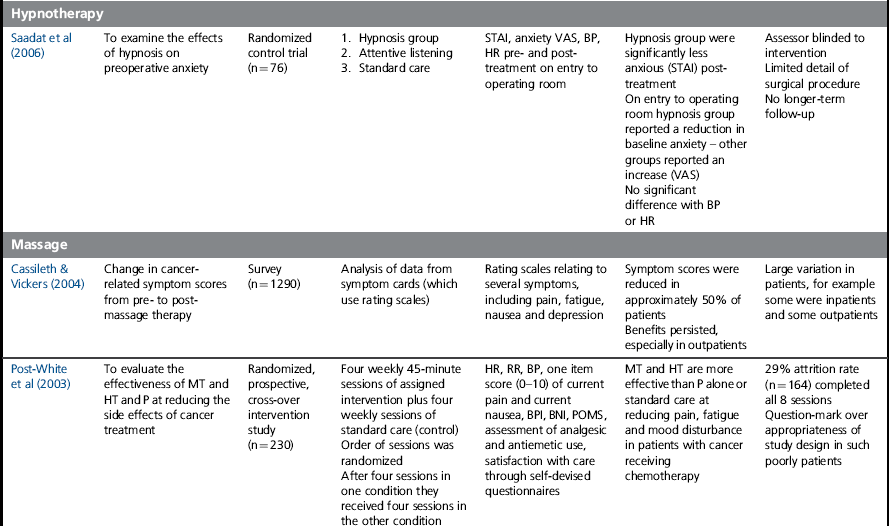

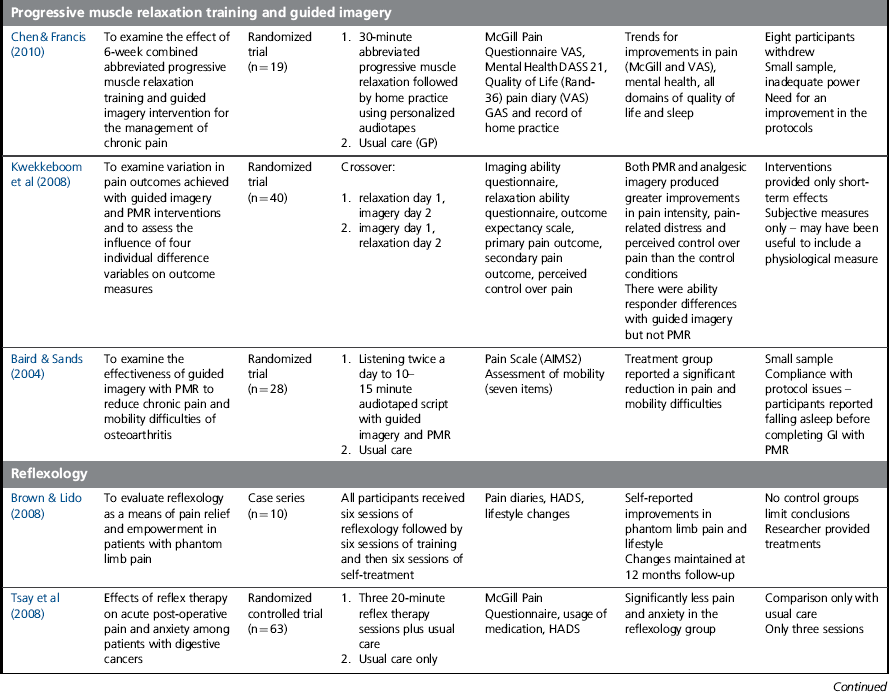

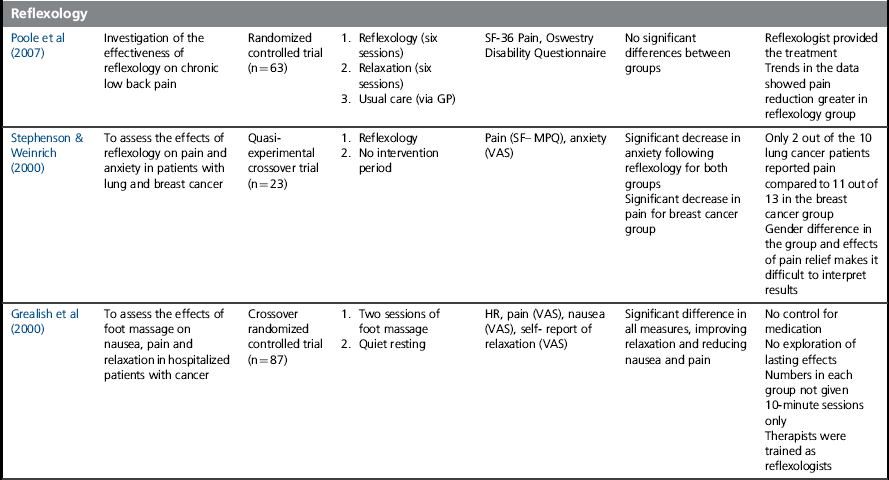

The manipulation of soft tissue, in the form of massage, aromatherapy or reflexology, carries with it many possible benefits, some as yet not fully understood or evaluated within clinical care. In relation to pain, some of the improvements following touch can be linked to the gate theory of pain perception (see Chapter 6). The work of the Touch Research Institutes (see resources section) and others have helped to clarify the benefits of massage for people with cancer and to diminish safety concerns. Using a number of validated physiological and psychological measures, massage has been demonstrated to reduce cortisol levels, levels of anxiety and the perception of pain (Stringer et al 2008). The following section will examine the evidence for specific therapies, with examples of research illustrating the growing evidence base and identifying the outcomes and limitations of the studies (see Table 15.1). They represent only a sample of the work available and readers are recommended to conduct a more in-depth search to supplement these observations.

Table 15.1

Aromatherapy and the clinical use of essential oils

Aromatherapy is the systematic use of essential oils in treatments to improve physical and emotional well-being (National Occupational Standards for Aromatherapy 2002

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree