COMA

ERIC W. GLISSMEYER, MD AND DOUGLAS S. NELSON, MD, FACEP, FAAP

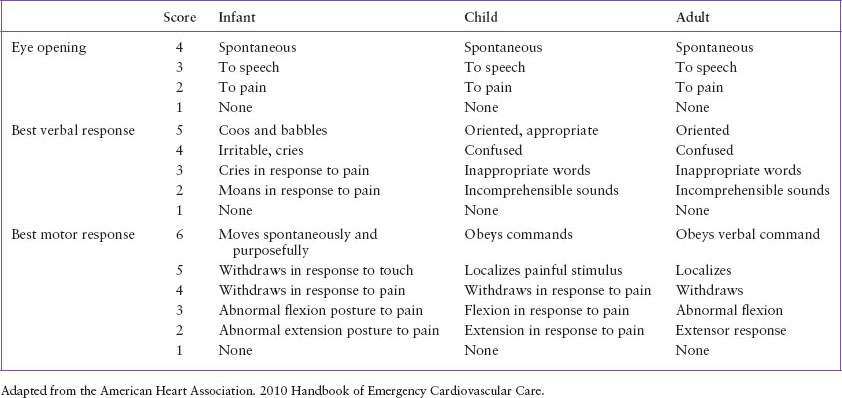

Consciousness refers to the state of being awake and aware of oneself and one’s surroundings. It is a basic cerebral function that is not easily compromised; impairment of this faculty may therefore signal the presence of a life-threatening condition. An altered level of consciousness (ALOC) is not in itself a disease but a state caused by an underlying disease process. Coma refers to a state lacking wakefulness and awareness from which a patient cannot be roused; this represents the most extreme form of ALOC. The term coma is often modified with descriptors such as light or deep. Lesser levels of impairment are described using other terms whose meanings may overlap. Lethargy refers to depressed consciousness resembling a deep sleep from which a patient can be aroused but into which he or she immediately returns. A patient is said to be stuporous or obtunded when he or she is not totally asleep but demonstrates greatly depressed responses to external stimuli. Not all ALOC states produce a diminished mental state, but may include abnormal activation of consciousness such as in delirium (see Chapter 8 Agitated Child). Because neurologic status may vary dramatically over time, it may be difficult to summarize such symptoms using a single descriptor and, as noted above, meanings of terms may overlap. Therefore, recording the comatose patient’s specific response (e.g., body movement, type of vocalization) to a defined stimulus (e.g., a sternal rub) is usually preferable (Table 12.1).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The state of wakefulness is mediated by neurons of the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) located in the brainstem and pons. Neural pathways from these locations project throughout the cortex, which is responsible for awareness. If the function of these neurons is compromised or if both cerebral hemispheres are sufficiently affected by disease, an ALOC will result.

Proper function of the ARAS and cerebral hemispheres depends on many factors, including the presence of substrates needed for energy production, adequate blood flow to deliver these substrates, absence of abnormal serum concentrations of metabolic waste products or extraneous toxins, maintenance of body temperature within normal ranges, and the absence of abnormal neuronal excitation or irritation from seizure activity or central nervous system (CNS) infection.

Disorders that produce coma by raising intracranial pressure (ICP) increase the volume of an existing intracerebral component such as brain or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) within the confined space of the cranial cavity. Alternatively, a new component such as a tumor or extravasated blood may be introduced. The brain can initially compensate for this altered volume relationship by regulating blood flow and CSF production. When the limits of these compensatory mechanisms are reached, ICP will rise abruptly, decreasing cerebral perfusion pressure (defined as mean arterial pressure minus ICP) and placing the patient at risk for herniation (see Chapter 121 Neurotrauma).

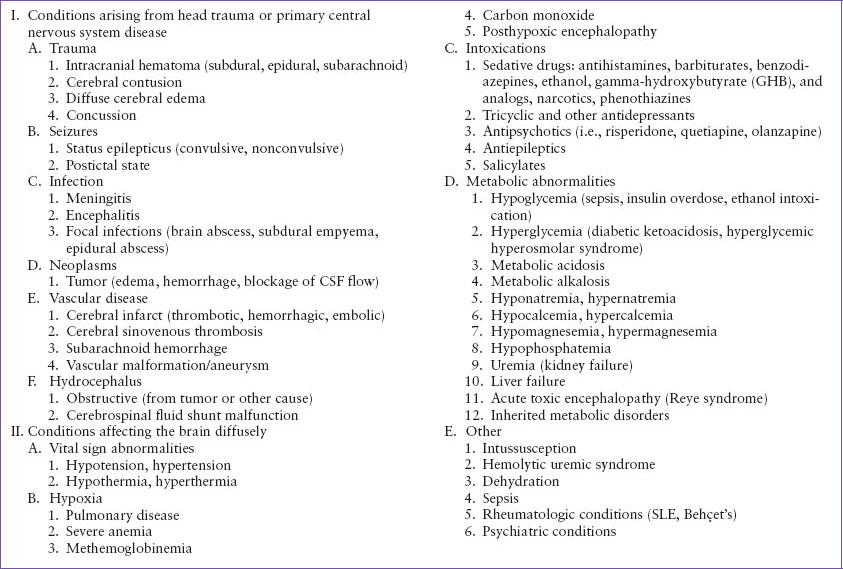

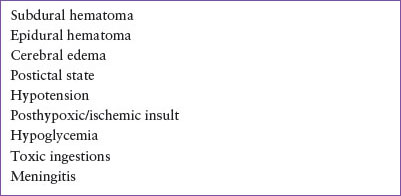

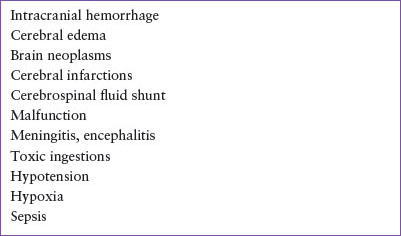

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

A differential diagnosis for children presenting in or near coma is shown in Table 12.2. The more commonly encountered causes of coma are listed in Table 12.3. These most likely causes of coma should be considered in every patient presenting with this condition. Life-threatening causes of ALOC are listed in Table 12.4 and must be considered in every patient. If present, these disorders require emergent treatment. More than one problem may be present simultaneously; for example, a victim of submersion injury may incur head trauma when falling into a swimming pool, or a deeply postictal patient with known seizure disorder may have ingested a toxin.

Primary Central Nervous System Disorders

Trauma

Coma-producing brain lesions that result from trauma include subdural and epidural hematomas, intraparenchymal and subarachnoid hemorrhage, penetrating injuries, cerebral contusion, diffuse cerebral edema, and concussion (see Chapter 121 Neurotrauma). Though most pediatric head injuries are blunt in nature and are accompanied by a history of trauma, abusive head trauma is also common and may present with nonspecific complaints. Patients suffering head trauma may present in a comatose state or may be alert for variable periods after impact.

ALOC resulting from diffuse cerebral edema and diffuse axonal injury is common in children and is less amenable to neurosurgical intervention than epidural and subdural hematomas. Characteristic CT findings of loss of gray–white interface may not be visible for 12 to 24 hours after the trauma was sustained. When radiographic abnormalities appear, they may be similar to those produced by hypoxia.

Concussion is an inexact term for a transient alteration in normal neurologic function after experiencing head trauma. A postconcussion syndrome may last for hours to days and is characterized by nausea, vomiting, dizziness, headache, and lethargy, with some symptoms lasting for weeks in some patients. Neuroimaging studies are normal, yet patients may be symptomatic enough to require admission for observation and intravenous (IV) hydration.

Seizures

Consciousness is greatly diminished both during and after periods of seizure activity. Although generalized seizure activity is readily recognizable by the rhythmic motor activity accompanying an ALOC, partial or absence seizure activity may present in a more subtle fashion with staring, tremors, eye blinking, rhythmic nodding, or other inappropriate repetitive motor activity. Seizures of all types, except absence and simple partial seizures, are usually followed by a postictal period, during which obtunded patients gradually regain consciousness. Patients in nonconvulsive status epilepticus may present in coma, and if other causes have been ruled out, comatose patients should have an electroencephalogram (EEG) performed.

TABLE 12.1

GLASGOW COMA SCALE AND MODIFICATIONS FOR INFANTS AND CHILDREN

TABLE 12.2

ETIOLOGY OF ACUTE-ONSET COMA/ALTERED LEVEL OF CONSCIOUSNESS

TABLE 12.3

COMMON CAUSES OF COMA/ALTERED LEVEL OF CONSCIOUSNESS

The diagnostic approach toward a patient with ALOC from seizure activity varies based on whether seizures have occurred in the past and the progression or resolution of his or her neurologic abnormalities (see Chapter 67 Seizures). Posttraumatic or new focal seizures are assumed to reflect an intracranial lesion until proven otherwise. Children taking antiepileptic medications benefit from drug-level measurement (if available for the medication) during an observation period. Subtherapeutic antiepileptic drug levels are one of the most common causes of seizures in this population. Subtherapeutic levels result in convulsions with postictal ALOC, whereas supratherapeutic levels less commonly result in seizure, but often produce ALOC of a different appearance based on the medication involved. The presence of fever may indicate that a febrile seizure has occurred or, if normal consciousness is not regained, that the patient has contracted a CNS infection such as meningitis or encephalitis (see Chapters 102 Infectious Disease Emergencies and 105 Neurologic Emergencies). The new onset of afebrile generalized seizures requires a more elaborate evaluation, as detailed in Chapter 67 Seizures.

Infection

Coma-inducing infections of the CNS may involve large areas of the brain and surrounding structures, as in meningitis or encephalitis, or they may be confined to a smaller region, as in the case of cerebral abscess or empyema (see Chapter 102 Infectious Disease Emergencies). Bacterial meningitis remains the most common infection severe enough to produce severe ALOC. Despite the overall decrease in cases since the introduction of vaccines effective against Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae, infections with the latter organism and Neisseria meningitidis still occur and are now the most common etiologic agents after the neonatal period. In some regions, Borrelia burgdorferi is a common cause of meningitis as part of Lyme disease. Meningitis may also be caused by viral (enteroviruses, herpes), fungal (Candida, Cryptococcus), mycobacterial (tuberculosis), and parasitic (cysticercosis) organisms. These nonbacterial infections usually have a slower onset of symptoms. The incidence of viral meningitis peaks in late summer, when enterovirus infections are most common.

TABLE 12.4

LIFE-THREATENING CAUSES OF COMA/ALTERED LEVEL OF CONSCIOUSNESS

Encephalitis, or inflammation of brain parenchyma, may also involve the meninges (see Chapter 102 Infectious Disease Emergencies). It occurs most commonly as a result of viral infection or immunologic mechanisms. Mumps and measles viruses were common etiologic agents before immunizations against these diseases, and they still occur in unimmunized individuals. Varicella encephalitis occurs 2 to 9 days after the onset of rash. The incidence of arthropod-borne encephalitides varies by geographic location but usually peaks in late summer and early fall. The herpes simplex virus remains the most common devastating cause of encephalitis, causing death or permanent neurologic sequelae in more than 70% of patients. It affects the temporal lobes most severely (outside the neonatal period), leading to seizures and parenchymal swelling, which can cause uncal herniation.

Focal CNS infections include brain abscesses, subdural empyemas, and epidural abscesses (see Chapter 102 Infectious Disease Emergencies). Brain abscesses occur most often in patients with chronic sinusitis, chronic ear infection, dental infection, endocarditis, or uncorrected cyanotic congenital heart disease. One-fourth of the cases of brain abscess occur in children younger than 15 years of age, with a peak incidence between 4 and 7 years of age. Subdural empyema also occurs secondary to chronic ear or sinus infection, but it is most commonly seen as a sequela of bacterial meningitis. Cranial epidural abscess is rare, but most cases occur from extension of sinusitis, otitis, orbital cellulitis, or calvarial osteomyelitis.

Neoplasms

Alterations in consciousness as a result of intracranial neoplasms (see Chapter 106 Oncologic Emergencies) may be caused by seizure, hemorrhage, increases in ICP caused by interruption of CSF flow, or direct invasion of the brainstem by the malignancy. The location of the tumor determines additional symptoms: Ataxia and vomiting for infratentorial lesions versus seizures, hemiparesis, and speech or intellectual difficulties resulting from supratentorial neoplasms. Hydrocephalus caused by tumor growth most commonly presents with headache (especially morning headache), lethargy, and vomiting.

Vascular

Coma of cerebrovascular origin is caused by interruption of cerebral blood flow (stroke) as a result of hemorrhage, thrombosis, or embolism (see Chapter 105 Neurologic Emergencies). Hemorrhage is often nontraumatic, stemming from an abnormal vascular structure such as an arteriovenous malformation (AVM), aneurysm, or cavernous hemangioma. Rupture of an AVM is the most common cause of spontaneous intracranial bleeding among pediatric patients. The hemorrhage is arterial in origin and located within the parenchyma, but it can rupture into a ventricle or the subarachnoid space. Aneurysm rupture is less common and is unusual in that repetitive episodes of bleeding may occur (“sentinel bleeds”), with rising morbidity and mortality from each subsequent episode of bleeding. Subarachnoid blood may be present in either case, although more commonly with aneurysm rupture. Cavernous and venous hemangiomas are lower-flow lesions that produce a less acute onset of symptoms.

Stroke may also occur from thrombosis or embolism of a normal vessel. Cerebral infarction caused by occlusion of the anterior, middle, or posterior cerebral artery usually produces focal neurologic deficit rather than coma. Acute occlusion of the carotid artery, however, may produce sufficient unilateral hemispheric swelling to cause herniation and coma. Cerebral sinovenous thrombosis is most commonly seen with hypercoagulable states or as a sequela of infections of the ear or sinus.

Swelling or hemorrhage from infarcted brain can cause increased ICP, leading to decreased parenchymal blood flow and resultant coma. Focal symptoms vary based on the size and location of brain with inadequate blood supply. Vascular accidents in the cerebellum present with combinations of ataxia, vertigo, nausea, occipital headache, and resistance to neck flexion. Coma is an unusual early sign of infarction of cerebral structures but becomes more common as lower anatomic centers are affected. Occlusion of the basilar artery may result in upper brainstem infarction, resulting in rapid onset of coma, as does hemorrhage or infarction of the pons. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES, a.k.a. reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome [RPLS]) causing ALOC is associated with autoimmune disease, sepsis, nephrotic syndrome, or immunosuppressive agents.

Cerebrospinal Fluid Shunt Problems

Children with congenital or acquired hydrocephalus as a result of prematurity, neoplasm, or trauma depend on the continued function of a neurosurgically placed shunt to drain CSF and to prevent rises in ICP (see Chapter 130 Neurosurgical Emergencies). The most common shunt type is ventriculoperitoneal (VP), draining CSF from a lateral cerebral ventricle, through a small hole in the skull, through a valve with an attached reservoir beneath the scalp and into the peritoneum via tubing placed under the skin of the neck, chest, and abdomen. CSF shunts may malfunction for many reasons, including tubing rupture, valve malfunction, tubing blockage, tubing disconnection, and shunt infection. The risk of failure is greatest during the first 6 months after shunt placement or revision.

Systemic Abnormalities

The second major category of disorders causing coma listed in Table 12.2 arises in organs other than the CNS and affects the brain diffusely. These abnormalities alter neuronal activity by a variety of mechanisms, including decreasing metabolic substrates required for normal function (e.g., hypoxia, hypotension, hypoglycemia, other electrolyte abnormalities), altering the rate of intracellular chemical reactions (e.g., hypothermia, hyperthermia), and introducing extraneous toxins into the CNS. Children with autoimmune disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Behçet disease, multiple sclerosis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM, a.k.a. postinfectious encephalitis) may present with ALOC due to inflammation of brain parenchyma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree