Immediate Management of Life-Threatening Problems

Coma is defined as the total absence of arousal and awareness lasting at least 1 hour associated with injury or functional disruption of the ascending reticular activating system in the brainstem or bilateral cortical structures. Comatose patients demonstrate no eye opening, speech, or spontaneous movements, and motor activity elicited by painful stimuli (if present) is abnormal or reflexive rather than purposeful. Coma must be differentiated from other pathologic changes in consciousness such as brain death, vegetative state, and delirium, although it may be difficult to do so in the emergency department.

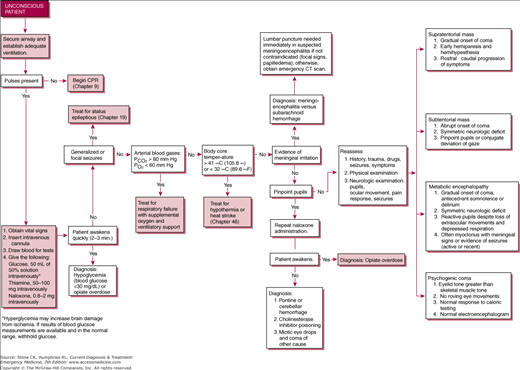

Initial management of the comatose patient involves the same steps needed to manage any critically ill patient presenting to the emergency department. Immediate assessment and support of airway, breathing, and circulation should be performed before efforts to diagnose or address specific causes of coma are undertaken, with the caveat that consideration may be given to postponing intubation until administration of empiric therapy for coma. Empiric therapy, often abbreviated by the acronym “D.O.N.T.” consists of IV dextrose, supplemental oxygen, IV naloxone, and thiamine. Dextrose (50 mL of 50% solution in adults) reverses coma secondary to hypoglycemia and is indicated if rapid testing of blood glucose is unavailable. Oxygen therapy should be initiated to immediately correct possible hypoxemic induced coma. Naloxone (0.4–2.0 mg IV) rapidly reverses coma and respiratory depression secondary to narcotic overdose but because of short half-life, multiple doses may be required. Thiamine (100 mg IV) is commonly given along with dextrose to avoid precipitating Wernicke encephalopathy in predisposed patients. Flumazenil (0.2 mg/min IV) specifically antagonizes benzodiazepines but is not routinely given empirically as it may precipitate seizures that are then refractory to benzodiazepines. It may be indicated in iatrogenic coma secondary to excess benzodiazepine administration.

If coma persists following the administration of naloxone and dextrose, definitive management of airway and breathing should be considered. IV access with two large-bore IVs should be obtained and blood pressure (especially hypotension) managed aggressively. A complete set of vital signs, including temperature and pulse oximetry, is essential to avoid missing coma complicated by severe hypo- or hyperthermia and hypoxia. Cervical spine immobilization should be maintained if there is any suspicion of trauma. A focused physical examination should be performed to evaluate for potential precipitating factors (evidence of drug use, systemic trauma, etc). Obtaining additional history from friends, relatives, bystanders, and EMS personnel is essential.

Neurologic assessment in comatose patients is of paramount importance, and a structured evaluation should be conducted as soon as possible once immediate threats to life have been addressed. Level of consciousness, cranial nerve examination, and motor examination should be performed. Lateralizing deficits and a rostrocaudal progression of brainstem dysfunction are seen with structural lesions, while involuntary movements are suggestive of a metabolic cause of coma. Although originally developed for traumatic brain injury, the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) has been shown to have predictive value in many different types of coma. Both total and component (eye, verbal, motor) scores should be documented (see Table 17–1).

| Component | Score | Adult | Child <5 years | Child >5 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor | 6 | Follows commands | Normal spontaneous movements | Follows commands |

| 5 | Localizes pain | Localizes to supraocular pain (>9 months) | ||

| 4 | Withdraws to pain | Withdraws from nailbed pressure | ||

| 3 | Flexion | Flexion to supraocular pain | ||

| 2 | Extension | Extension to supraocular pain | ||

| 1 | None | None | ||

| Verbal | 5 | Oriented | Age-appropriate speech/vocalizations | Oriented |

| 4 | Confused speech | Less than usual ability; irritable cry | Confused | |

| 3 | Inappropriate words | Cries to pain | Inappropriate words | |

| 2 | Incomprehensible | Moans to pain | Incomprehensible | |

| 1 | None | No response to pain | ||

| Eye opening | 4 | Spontaneous | Spontaneous | |

| 3 | To command | To voice | ||

| 2 | To pain | To pain | ||

| 1 | None | None |

Cranial nerve examination (especially pupillary response) is an essential part of the neurologic examination and may assist in determining the level of brainstem dysfunction (see Table 17–2). Normal pupillary function and eye movements may be seen in lesions rostral to the midbrain. Pupillary abnormalities (especially unilateral) may be an early indicator of herniation, and pupillary function should be assessed frequently when increased intracranial pressure (ICP) is a concern. Symmetrically reactive pupils that are unusually large or small are commonly secondary to drug ingestions.

| Reflex | Examination Technique | Normal Response | Brainstem Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pupils | Response to light | Direct and consensual restriction | Midbrain |

| Oculocephalic | Turn head from side to side | Eyes move conjugately in direction opposite to head | Pons |

| Vestibulo-oculocephalic | Irrigate external auditory canal with cold water | Nystagmus with fast component away from stimulus | Pons |

| Corneal reflex | Stimulation of cornea | Eyelid closure | Pons |

| Cough reflex | Stimulation of carina | Cough | Medulla |

| Gag reflex | Stimulation of soft palate | Symmetric elevation of soft palate | Medulla |

Motor examination should focus on the presence of movements and whether they are involuntary, reflexive, or purposeful. Purposeful movements such as localization require some degree of cortical processing, while reflexes are stereotypical responses that occur in the absence of cortical input. Structural lesions may result in posturing. Decerebrate posturing, characterized by extension of both upper and lower extremities, is seen in lesions caudal to the midbrain. Decorticate posturing, characterized by flexion of the upper extremities and extension of the lower extremities, is seen in lesions rostral to the midbrain.

Herniation syndromes result from increased ICP and lead to brainstem compression, manifested by arterial hypertension, bradycardia, and respiratory irregularities (Cushing triad). Herniation may be classified as uncal, central, or cerebellar (see Table 17–3). Increased ICP commonly results from a space-occupying lesion such as a tumor or hematoma but may also result from cerebral edema secondary to trauma, infection, or severe metabolic derangements.

| Sign | Mechanism | Type of Herniation |

|---|---|---|

| Coma | Compression of midbrain tegmentum | Uncal, central |

| Pupillary dilation | Compression of ipsilateral third nerve | Uncal |

| Miosis | Compression of the midbrain | Central |

| Lateral gaze palsy | Stretching of CN VI | Central |

| Hemiparesis | Compression of contralateral cerebral peduncle | Uncal |

| Decerebrate posturing | Compression of the midbrain | Central, uncal |

| Hypertension, bradycardia | Compression of the medulla | Central, uncal, cerebellar |

| Abnormal breathing | Compression of the pons or medulla | Central, uncal, cerebellar |

Treatment of increased ICP focuses on maintaining cerebral perfusion pressure, defined as mean arterial pressure (MAP) minus ICP. The goal is to keep CPP > 70–80 mm Hg. The Monro-Kellie principle states that the volume within the skull is fixed and contains three components: brain, blood, and CSF. Increase in the amount of these components (eg, cerebral edema, hematoma, hydrocephalus) or the addition of other components (eg, tumor) results in increased ICP. Using this principle, treatment is aimed at either reducing the volume of the components or expanding the volume available through surgical decompression.

Emergency department care of herniation consists initially of prompt recognition and maximizing resuscitation. Hypoxia and hypotension must be avoided and other adverse systemic factors such as hyperglycemia and fever treated aggressively. The patient’s head should be elevated at 30° and adequate sedation and analgesia provided. Seizure prophylaxis should be considered, particularly when paralytics have been given. When available, further treatment should be guided by ICP monitoring. In the absence of ICP monitoring, hyperventilation to a Paco2 of 30–35 mm Hg should be initiated, followed by mannitol (0.25–1.0 g/kg IV) or hypertonic saline (2 mL/kg of 7.5% solution IV). If the ICP remains high and craniectomy is not indicated or not available, barbiturates may be used to decrease cerebral metabolism and thus cerebral blood flow. Induced hypothermia to 32–34°C has been shown to effectively lower otherwise refractory ICP.

Further Evaluation of the Comatose Patient

The differential diagnosis of coma is broad and includes primary cerebral disorders (bilateral/diffuse, unilateral with mass effect, and brain-stem disorders) as well as a number of systemic derangements (see Table 17–4).

|

History should be obtained from whatever sources are available, including friends, bystanders, police, and EMS personnel. Crucial points include the following:

- Recent head trauma, even seemingly trivial

- Drug use (including alcohol), recent or past

- Past medical history, including a history of seizures, diabetes, cirrhosis, or other neurologic disease

- Medications, including narcotics and benzodiazepines use

- Precomatose activity and behavior (headache, confusion, vomiting)

- Sudden versus gradual onset of coma

- Other individuals with similar symptoms

The physical examination (other than the neurologic examination) should focus on ruling out other threats to life such as hypovolemia and systemic trauma. Evidence of trauma elsewhere on the body is presumptive evidence of head trauma in the comatose patient.

Non-contrast head CT is an integral part of the workup for coma that is not obviously related to hypoglycemia, overdose, or other metabolic cause, and should be strongly considered in any patient who remains comatose after dextrose and naloxone. Contrast-enhanced head CT or MRI may be indicated in certain patient populations.

Electrolytes, LFTs, CBC, UA, glucose, urine/serum toxicology screens, thyroid function studies, BUN/Cr, and ABG should be obtained early in the evaluation of coma. Lumbar puncture and CSF analysis should be performed if not contraindicated (eg, mass lesions or other evidence of increased ICP) in patients for whom the cause of coma is unclear or in whom an infectious cause or SAH is suspected. ECG should be obtained and cardiac monitoring instituted to eliminate cardiac arrhythmias as a contributing factor. An EEG should be obtained when possible, especially in intubated patients receiving paralytics and in those for whom nonconvulsive status epilepticus is a consideration.

Emergency Treatment of Specific Disorders Causing Coma

See also Chapter 37.

- Headache, nausea, vomiting

- Hypertension

- Focal neurologic deficit with signs of increased ICP

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) can be classified as primary (unrelated to congenital or acquired lesions) or secondary (related to vascular malformations, tumors, or other lesions). The vast majority of primary ICH is related to hypertension and occurs in characteristic areas of the brain: cerebral lobes, basal ganglia, thalamus, pons, and cerebellum. Secondary ICH is more variable in location. Smoking, advanced age, and anticoagulant use are other risk factors for ICH. Early hematoma growth is more common than previously thought and is most likely responsible for sudden deterioration within the first 6 hours of initial presentation. Cytotoxic and vasogenic edema surrounding the hemorrhage may result in ischemia and are likely responsible for delayed deterioration.

Presentation is related to the size and location of the hemorrhage (see Table 17–5). Patients with large areas of hemorrhage are often comatose on arrival. The majority of patients with brainstem or cerebellar hemorrhage present with a decreased level of consciousness necessitating intubation. Headache is universally present in awake patients and may accompany other signs of increased ICP. Seizures occur in 10% of all ICH but in 50% of patients with lobar hemorrhage. Most patients are hypertensive on presentation, even if previously normotensive. Non-contrast CT scan is the diagnostic study of choice with CT angiography being useful in certain patient populations.

| Location | Findings |

|---|---|

| Basal ganglia | Contralateral motor deficits, gaze paresis, aphasia |

| Thalamus | Contralateral sensory loss |

| Cerebellum | Nausea, vomiting, ataxia, nystagmus, AMS, ipsilateral gaze/facial palsy |

| Pons | Coma, pinpoint pupils, autonomic instability, quadriplegia, altered respiratory patterns |

Care is primarily supportive and aimed at reducing ICP and controlling blood pressure. Aggressive blood pressure control using IV labetalol, esmolol, or nicardipine should be instituted with a target SBP < 180 mm Hg or MAP < 130 mm Hg. CPP should be maintained > 70. Patients on anticoagulants should receive reversal agents (FFP and vitamin K for warfarin, protamine for heparin) promptly. The use of prothrombin complex concentrate, factor IX complex concentrate, and rFVIIa have been shown to reverse the elevation of the INR very rapidly (often within 1–2 hours) and is faster to prepare than FFP. Corticosteroids are contraindicated. Prompt neurosurgical consultation should be obtained for all patients with declining neurological status or evidence of hydrocephalus on CT scan. Cerebellar hemorrhages > 3 cm require surgery. Hemorrhages in typical locations may not need further diagnostic evaluation and are rarely amenable to surgery. All patients should be admitted for further care.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree