Chronic Pain Syndromes

Michael A. Turturro and Paul M. Paris

Pain is typically defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional phenomenon associated with actual or potential tissue damage. Chronic pain is defined as a sustained painful experience that in most cases persists beyond the time in which tissue damage occurs. Although acute pain typically has a rapid onset coinciding with tissue damage, it typically resolves as tissue heals. It serves as a biologic warning of potential illness or injury, prompting the individual to protect the painful area and seek medical attention. Although distressing and anxiety provoking, it usually can be treated effectively with proper selection and use of analgesic drugs.

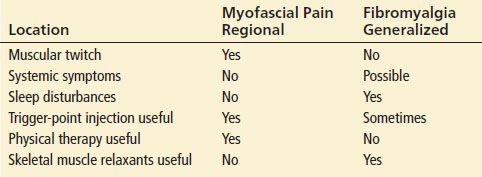

Chronic pain differs from acute pain in many respects (Table 16.1). In chronic pain, the symptom of pain itself often becomes more of a problem than its underlying cause, altering the patient’s well-being and frequently causing both disability and depression. It has been estimated that about 30% of the US population suffers from chronic pain, and the loss of productive time as a result costs more than $60 billion a year (25); additional expenditures are also incurred from health care and litigation related to chronic pain syndromes. The treatment of chronic pain is complex and difficult. Success in treating chronic pain typically requires a multidisciplinary team approach, using various regimens of pharmacotherapy, physical therapy, and behavioral therapy to both reduce pain and restore function.

TABLE 16.1

Differences Between Acute and Chronic Pain

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Patients with chronic pain syndromes are commonly encountered in the emergency department (ED) and often present a management challenge for the emergency physician. Some present with vague signs and symptoms and often are not definitively diagnosed on the first encounter. Treatment is typically complex, requiring several regimens of varying effectiveness. Many patients have other psychological disturbances and a protracted course of exacerbations and remissions, with failures of various therapies. They may be demanding and frustrating for the clinician, because their conditions are not easily managed. Patients may feel uncomfortable with a physician who has not been their regular caretaker. The presentation of patients requesting controlled substances for illicit means may overlap with the presentation of chronic pain exacerbations. As a result, malingering or drug-seeking behavior may inappropriately be suspected in patients with chronic pain syndromes.

In each patient with chronic pain, the development of progressive or new pathology must be considered, and the physician should not simply assume that a patient’s chronic pain exacerbation is nothing more than a worsening of an already existing disease process. For example, in a patient with increasing chronic low back pain, one must consider the possibility of new spinal cord pathology. Simply providing analgesics without consideration of acute pathology may result in missing serious disease.

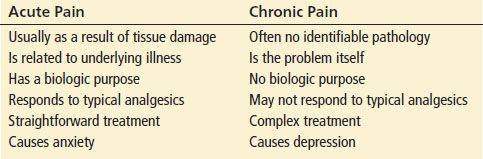

Chronic pain syndromes typically fall into one of the categories listed in Table 16.2.

TABLE 16.2

Categories of Chronic Pain Syndromes

Although patients with pain as a result of prolonged tissue destruction can be treated successfully with appropriately titrated analgesics in the ED, patients in the remaining categories should also be referred to a chronic pain management center whenever feasible, to facilitate the management of the chronic pain syndrome in a multidisciplinary manner.

Communication between the emergency and pain service physicians fosters a team approach to the management of chronic pain exacerbations. For example, a pain contract and/or specific patient care plan may be developed between the patient, the pain service, the primary care physician, and the ED regarding when the patient will be expected to present to the ED for a pain exacerbation, the analgesic that will be used after appropriate evaluation, and the quantity of analgesics to be prescribed on discharge.

Although chronic pain as a result of any cause may be exacerbated by psychological factors, the pathophysiology of chronic pain without obvious tissue pathology is still being elucidated. Prolonged noxious sensory input from the periphery may result in self-sustaining central neural activity, possibly by reducing inhibitory input into the central nervous system (CNS) and producing changes in neurontransmission at spinal neuron synapses (27). Activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors appears to be central to this process. This phenomenon, known as “windup,” essentially produces a memory effect for pain perception in the CNS. These effects persist despite the lack of ongoing tissue injury. As a result, patients become increasingly more sensitive to painful stimuli.

Chronic pain commonly causes the patient to lose a sense of control over his or her environment. Allowing patients to become passively dependent on health care practitioners and medical therapy only feeds this vicious cycle of illness and the helpless victim.

Drug Abuse and Addiction

Drug abuse and addiction are unfortunate yet common problems in our society, and approximately 8% of all adult patients are actively abusing illicit drugs. Unintentional prescription opioid analgesic deaths increased more than 500% between 1999 and 2010, continues to rise, and is now higher than deaths from cocaine and heroin use combined, as well as higher than annual deaths from vehicular trauma (13). Drug abusers (whether or not they suffer from chronic pain) tend to patronize EDs on a frequent basis to obtain opioid analgesics. Because of this, ED staff members may develop a bias against many chronic pain patients. Because it may be difficult to differentiate patients with exacerbations of chronic pain from patients who are seeking drugs for abuse and there are no validated tools to help the clinician distinguish abuse from undertreated pain, many patients with real exacerbations of chronic pain are consequently labeled as drug abusers.

It is important to distinguish between opioid dependence, tolerance, and addiction. Dependence refers to the physical phenomenon in which sudden withdrawal of the drug results in a drug-specific withdrawal syndrome. This occurs in patients chronically using opioid analgesics, whether for legitimate or illicit purposes. Tolerance refers to the physical phenomenon of a decrease in drug effect at a specific dose over time, requiring increasing doses to produce the desired effect, whether it is analgesia or euphoria. Tolerance often occurs as a result of downregulation or desensitization of opioid receptors, resulting in a physiologic resistance to opioid therapy (2). Additional physiologic changes may occur at the cellular level with chronic opioid therapy, which may result in abnormally increased sensitivity to painful stimuli.

Dependence and tolerance must be distinguished from addiction, which is the psychobiologic state of compulsive use despite signs of toxicity, preoccupation with obtaining and using a substance, and inability to function as a result of compulsive use. With legitimate prolonged use of opioid analgesics for chronic pain, dependence and tolerance do occur; however, addiction is uncommon. Conversely, when pain medication is withheld from patients with chronic pain, such patients may learn pain avoidance or maladaptive behaviors to obtain opioids. These drug-seeking behaviors do not imply addiction but inappropriate techniques used by patients to satisfy a physiologic need state. This phenomenon is often referred to as pseudoaddiction. Underdosing and giving pain medication on an as-needed basis for sustained pain (rather than around-the-clock dosing) contribute to this phenomenon, as the patient learns to express both exaggeration of symptoms and maladaptive behavior to obtain the reward of receiving pain medication.

Drug abusers may have a history of medical noncompliance, discharge from pain services, polysubstance abuse, multiple visits for treatment of various nonspecific painful conditions, an unusual reluctance to try new therapies, or a report that their primary physician is unreachable. They may have a history of selling prescription drugs (diversion), forging prescriptions, using aliases, or injecting oral preparations. The use of a state prescription monitoring program may help identify patients who exhibit these behaviors (4). Because it is not appropriate and is unethical to withhold analgesics from patients experiencing pain unless the emergency physician has clear objective evidence that the patient is a drug abuser, the patient’s pain should be treated. Guidelines limiting the prescribing of opioid analgesics from the ED, while well intentioned and designed to reduce the harm of inappropriate opioid use, have the unintended consequence of potential undertreatment of patients with exacerbations of painful conditions, some of whom have limited access to care outside of the ED. Sometimes, a known substance abuser may present with an acutely painful condition. In these cases, pain should be adequately relieved in the ED, and judicious amounts of analgesics to be taken at regular intervals should be given on discharge. The use of opioid agonist–antagonists may be useful in these patients, as they are less likely to cause euphoria. However, they should not be given to a patient physically dependent on opioids, as they may precipitate withdrawal.

ED MANAGEMENT

Although many of the concepts that apply to acute pain management (see Chapter 15) also apply to patients with chronic pain, the endpoint of marked relief may not be attainable. Exacerbations of chronic pain (breakthrough pain) are often a result of a combination of both physical and psychological factors, and the primary goal in the ED is to reduce pain to the point where the patient becomes functional, with pain service referral when appropriate. In additon, certain pain syndromes (e.g., neuropathic pain) may not be effectively treated by the usual doses of typical analgesic agents. Therefore, an understanding of both the physical and psychological pathophysiologies associated with these disorders will ensure optimal treatment.

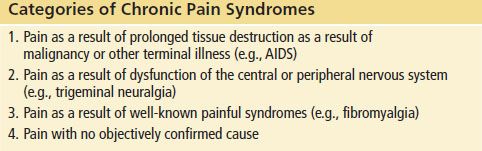

The treatment of chronic pain includes the use of many modalities (Tables 16.3–16.5). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen are often employed early in the patient’s course; however, many patients are unable to be adequately controlled with these agents alone.

TABLE 16.3

Therapies for Chronic Pain

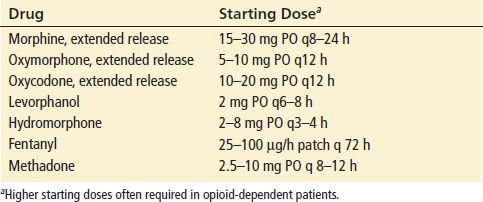

TABLE 16.4

Opioid Pharmacotherapy for Chronic Pain

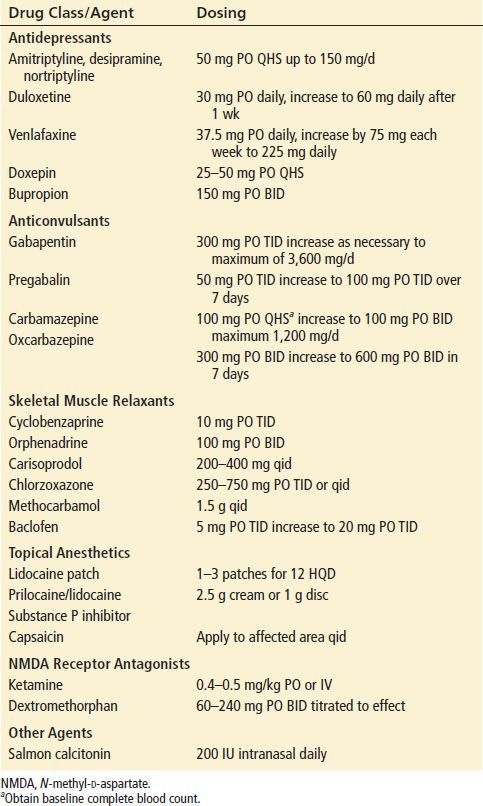

TABLE 16.5

Nonopioid Pharmacotherapy for Chronic Pain

Opioid analgesics are the most useful drugs in treating exacerbations of chronic pain. The agents used are discussed in the chapter on acute pain (see Chapter 15), but longer-acting preparations such as those listed in Table 16.4 may be more appropriate for the treatment of chronic pain. These agents also avoid the risk of aspirin or acetaminophen toxicity from the nonnarcotic component of combination products, which may occur when doses sufficient to provide adequate amounts of the opioid component are taken. The use of extended release preparations of oxycodone and oxymorphone has gained considerable attention as a result of its potential for abuse. In the ED, they should typically be reserved for patients with pain as a result of an advanced terminal illness such as malignancy, as alternatives can be successfully used in other patients.

Pain as a result of malignancy, although chronic in nature, may be considered sustained acute pain because it is typically associated with progressive tissue damage. Although nonnarcotic analgesics and physical therapy are often used to treat malignant pain, progressively increasing doses of opioid analgesics remain the mainstay of therapy. Despite the risk of opioid dependence, opioid analgesics should never be withheld from patients with terminal malignant pain, as pain control is the most important factor contributing to overall quality of life (16). Acute exacerbations of malignant pain must be treated as an emergency, with aggressive opioid analgesia. Higher doses of opioids titrated more rapidly than in opioid-naive patients are typically needed, and this approach is both safe and effective.

Tramadol is a centrally acting oral analgesic that activates opioid receptors in the CNS and also inhibits monoamine neurotransmitter reuptake (similar to tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs]). Tolerance and withdrawal symptoms appear to be absent with tramadol. However, it has been demonstrated to be less effective in the management of acute pain than other opioids when used alone (26) and is associated with a high incidence of side effects, including seizures. It appears to be most appropriate for adjunctive treatment in mild to moderate chronic pain.

TCAs are useful in treating chronic pain, both by controlling depression, increasing inhibitory fiber stimulation, and by altering nociceptive responses to painful stimuli, thereby altering the cerebral process in pain perception. They are effective in pain control even if no evidence of depression exists. TCAs are effective in various chronic pain syndromes, particularly neuropathic pain, facial pain syndromes, fibromyalgia, and arthritis. TCAs act synergistically with opioids in controlling chronic pain. It is likely that all TCAs are effective in treating chronic pain, but amitriptyline has been the most extensively studied. The recommended starting dose for all TCAs in managing chronic pain is half the antidepressant dose, which may be titrated up if necessary. Analgesic effects may not be evident for several days. Referral for follow-up is essential in patients started on TCAs in the ED. Available evidence suggests that other agents used for depression may be used but are less effective than TCAs in the management of most types of chronic pain (22). However, the serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), duloxetine and milnacipran, have been effectively used to treat neuropathic pain. The association between depression and chronic pain is clear, but in some patients the painful process produces depression, and in others chronic pain is a manifestation of a depressive disorder. In patients with chronic pain in whom no etiologic basis can be established, management is also focused on treating the underlying depression. In addition, depression is also known to increase opioid analgesic requirements.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) may be effective in certain acute and chronic pain syndromes. It is used most often in chronic low back pain and complex regional pain syndrome, although the evidence for its benefit is limited by the lack of well-designed clinical trials. In addition, most patients note a decrease in the analgesic effect over time. The “gate control” theory of pain postulates that in the periphery, small unmyelinated C fibers transmit nociceptive information, and large myelinated A fibers transmit light touch and pressure sensations. Both of these fibers synapse at the substantia gelatinosa in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Stimulation of the A fibers inhibits the transmission of nociceptive C fiber stimuli into the CNS, thereby “closing the gate.” By using electricity to stimulate the A fibers preferentially, the pain stimulus entering the CNS can be controlled.

In neuropathic pain syndromes, pain originates from peripheral nerve dysfunction. Therefore, anticonvulsants play a primary role in treating most of these disorders, with carbamazepine, gabapentin, and preganalin commonly used. In addition, because substance P may be the principal mediator of neuropathic pain, an effort to inhibit substance P may be beneficial. When applied topically, capsaicin, a substance derived from red chili peppers, releases substance P from primary afferent nerve fibers. With repeated application, capsaicin depletes substance P from these nerve fibers. Consequently, capsaicin may have some benefit in treating the neuropathic pain of postherpetic neuralgia, complex regional pain syndrome, metabolic neuropathy, and other chronic pain syndromes such as psoriatic and rheumatoid arthritis. Capsaicin causes skin redness and burning. This may also contribute to its analgesic effect, as peripheral counterirritation causes pain relief by a “gate-closing” effect, as described for TENS. However, this skin irritation also limits the concentration that may be used, thus reducing its potential efficacy (18). It has been postulated that in chronic pain, NMDA may play a central role in the windup phenomenon of sensitizing the CNS to a prolonged painful stimulus, possibly by recruitment of C fibers. Consequently, substances that antagonize the NMDA receptor are gaining attention as possible agents in the management of chronic pain. Ketamine, dextromethorphan, methadone, memantine, and amantadine all antagonize the NMDA receptor and have been studied as agents for chronic pain management (particularly in neuropathic pain). However, the doses needed to produce analgesia exceed the doses that cause untoward adverse effects (12).

Behavioral and physical therapy help patients cope with chronic pain and regain a sense of self-control, thus improving overall day-to-day function. The focus with these therapies is rehabilitation, not total pain relief. However, patients must be motivated to be successful.

The most effective ways to treat these chronic pain syndromes are the multidisciplinary approaches used by pain clinics, in which combinations of the various therapies are coordinated. Thus, the emergency physician should confer with the patient’s primary care or referring physician and make arrangements for follow-up before initiating or changing therapy.

SPECIFIC CHRONIC PAIN SYNDROMES

Chronic Low Back Pain

Chronic low back pain is the most common chronic pain syndrome seen in the ED. Approximately 8% of US adult patients develop nonspecific low back pain annually, and of these about 5% will continue to experience persistence after 3 months (7).

Opioid and nonopioid analgesics, including acetaminophen, remain the mainstay of therapy for chronic back pain. As with other chronic pain syndromes, tolerance and dependence can occur with prolonged opioid use, and gastrointestinal and renal damage can occur with prolonged NSAID use. Antidepressant therapy may be added to patients poorly controlled on analgesics alone. Skeletal muscle relaxants may improve range of motion, but their use is limited in chronic back pain owing to a high incidence of CNS side effects (drowsiness and dizziness).

In patients with sciatica, treatments specific for neuropathic pain may be beneficial, and trials using gabapentin or topiramate have shown modest improvement in pain relief as compared with placebo (6). Although sometimes prescribed, systemic corticosteroids have not been associated with any clinically significant benefit when compared with placebo.

Nonpharmacologic therapies have been used with varying degrees of success. Regular exercise with an emphasis on core stability appears to be important to improve function, and behavioral therapy, massage hydrotherapy, and acupuncture seem to have modest beneficial effects (5). A review of 26 randomized controlled trials on spinal manipulative therapy concluded that this intervention results in a clinically insignificant benefit on short-term pain relief (19). The evidence of effectiveness of other therapies such as traction and TENS is lacking, with studies either showing no benefit or conflicting results (14).

Myofascial Pain and Fibromyalgia

Myofascial pain syndrome and fibromyalgia are conditions in which acute or chronic muscle pain, stiffness, and tenderness occur at specific anatomic sites (“trigger points”). A trigger point is an area within a taut band of skeletal muscle that, when palpated, produces referred pain in the area in which the patient complains of pain (a “reference zone”). It may be activated by physical trauma, other trigger points, or psychological stress.

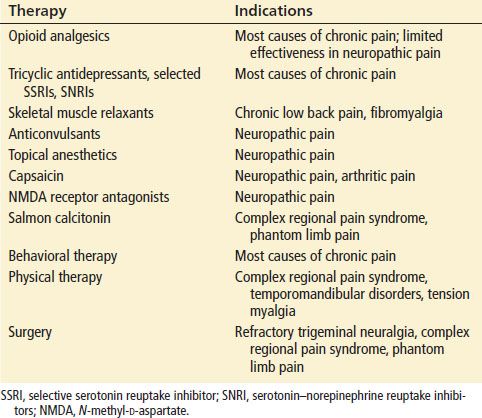

Fibromyalgia and myofascial pain syndrome may be considered opposites in the spectrum of a single disorder (Table 16.6). Myofascial pain tends to be localized, and the involved muscle group may twitch involuntarily. Fibromyalgia pain tends to be diffuse and is associated with systemic symptoms such as chronic fatigue, sleep disturbance, headaches, vertigo, visual disturbances, and irritable bowel syndrome. Symptoms may begin after an acute viral illness, trauma, or psychological stress. Physical findings may be nonspecific, and the patient may be told that the symptoms are unexplained or psychogenic.

TABLE 16.6

Myofascial Pain Syndrome Versus Fibromyalgia