INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Child maltreatment is, unfortunately, a common occurrence. In the United States, over 650,000 children suffer some form of child abuse or neglect each year, and approximately 12% of these children will present to a hospital with injuries.1 It is estimated that between 2% and 10% of children visiting the ED are victims of child abuse or neglect.2 Therefore, emergency physicians are in a unique position to identify nonaccidental injuries and potentially prevent further abuse. Child maltreatment takes many forms including neglect (68%), physical abuse (16%), sexual abuse (8%), and emotional abuse and medical child abuse (8%)1 (previously called Munchausen syndrome by proxy).

NEGLECT

Child neglect is the most common form of child maltreatment and the most difficult to evaluate and manage; it contributes to as many as 50% of fatalities from child maltreatment.3 Neglect occurs when a caregiver fails to meet a child’s basic needs in provision of food, shelter, clothing, health care, education, supervision, and nurturance.3,4,5 Further, this failure either results or is very likely to result in serious impairment of a child’s health or development. While many types of neglect may occur, seldom does any one form exist on its own. Carefully consider each neglect risk factor individually, identifying whether there is overt historical or physical evidence of each subtype of neglect (Table 148-1).

| Types of Neglect | Description |

|---|---|

| Physical | Failure to provide the basic physical necessities of food, shelter, and adequate clothing. |

| Emotional | Failure to provide necessary nurturing, affection, and stimulation. |

| Educational | Failure to provide an educational program; this may include chronic truancy. |

| Medical/dental | Failure to provide basic medical and dental care, which results, or has the potential to result, in harm; this may include noncompliance with healthcare recommendations. |

| Supervisory | Failure to adequately supervise and ensure safety of a child, given the child’s developmental needs. |

Given that neglect is rarely a single act, but is rather an accumulation of harm over time, the often brief, single encounter of an ED assessment cannot provide the comprehensive assessment required. The goals of the ED encounter are to recognize when child neglect may be at issue, to clearly document the presenting concerns, and to trigger the appropriate multidisciplinary team approach for the investigation and management of these complex cases. The recognition of child neglect in the ED requires knowledge of the multiple risk factors associated with neglect (Table 148-2).4,5,6,7 Poverty, parental substance abuse, and mental health issues are three of the most common risk factors for child maltreatment and neglect.4,6 Although not all poor families are neglectful, poverty has an overwhelming effect on the parents’ ability to provide basic care for their children and may contribute to social isolation and a lack of supports.7 Substance abuse may result in a parent who is both physically and emotionally unavailable to the child, and substance abuse may divert funds for basic necessities.

| Child risk factors | Premature birth Young age Multiple gestation (twin/triplet) births Chronic disability |

| Parent risk factors | Substance abuse Cognitive impairment Adolescent parents Domestic violence Mental health issues Lack of education/unrealistic expectations |

| Family/social risk factors | Isolation Single-parent families Unemployment Family illness History of involvement with child welfare services |

Children and adolescents may be brought to the ED for a variety of reasons when neglect is the underlying problem. Presenting symptoms may include failure to thrive, malnutrition, chronic respiratory or skin infections, repeated injuries, poisonings, behavioral problems, or mental health concerns. Children with chronic disabilities or chronic medical conditions may present repeatedly with clinical deterioration if a parent is noncompliant with healthcare recommendations.

Review the hospital record prior to obtaining the medical history from the parent. Be alert to chronic health problems, repeated accidents or injuries, and missed medical appointments. The medical history must address both the presenting complaint as well as any past illnesses or injuries. Note whether the parents are able to provide a clear history and are knowledgeable about their child’s health and developmental milestones. Document the child’s immunization status and any past or current medications. The young infant or child who presents with feeding problems or failure to thrive requires a thorough perinatal history as well as a detailed dietary record. In the case of maternal depression, the history provided by the mother may be vague and difficult to obtain. Inquiries into the family history should specifically address known risk factors for child neglect including parental mental health issues and substance abuse.

The physical examination begins during the process of gathering the history, with observations of the interaction between the parents and child, and notes on the child’s clothing and hygiene. Observe for unusual demeanor or extreme behaviors such as flat affect, listlessness, overt fear, or out-of-control behavior. Document objective growth parameters including weight, height, and head circumference, and compare with previously reported measures when possible. In general, weight is the first growth parameter to be adversely affected by inadequate nutrition.

The physical examination is typically focused on the system of chief complaint; however, concern for neglect should prompt special attention to the skin (bruises, scars, infection, diaper rash), hair (alopecia, lice infestation), and teeth (dental caries). Determine if muscular tone is decreased or increased. Ear, nose, throat, and respiratory examinations may reveal evidence of chronic, untreated infection. Abdominal exam should note any distention, organomegaly, or unusual masses. Look for evidence of peripheral edema. Note the presence of adequate subcutaneous fat as well as muscular development, particularly over the suprascapular and buttock regions.

Investigations vary depending on the severity of illness or injury. For failure to thrive, a comprehensive nutritional and metabolic profile is generally indicated. A complete skeletal survey should be considered in any situation of serious neglect to identify physical abuse and to assess skeletal abnormalities from nutritional deficiency or undiagnosed metabolic disease.

Focus on initial stabilization of acute medical illness and injury. For severe malnourishment with fluid and electrolyte imbalance, initial management may require intensive care support to manage metabolic complications such as “refeeding syndrome.” Most infants with failure to thrive due to environmental neglect will respond rapidly to appropriate feeding.

Educate the parents in a thoughtful, respectful, and culturally sensitive manner on the most urgent problems and need for further investigation and treatment. Early consultation with pediatric specialists or child abuse pediatricians is warranted for all concerns of child neglect, even if hospitalization is not indicated. Comprehensive management of child neglect requires frequent ongoing reevaluation, which goes beyond the routine duties of the emergency physician.

PHYSICAL ABUSE

Physical abuse accounts for approximately 16% of all cases of child abuse and is perhaps the most easily identified type of maltreatment.1 Child physical abuse is defined as injury inflicted on a child by a caregiver. Injuries can occur to all parts of the body, but the more commonly injured areas are the skin (bruising, burns), skeleton (fractures), head, and abdomen. Evaluate the child medically and treat injuries. Medical evaluation and treatment of the child always take precedence over the legal investigation. Although the forensic or legal evaluation is best performed by trained investigators or child abuse specialists, data gathered in the ED often guides and informs further investigation.

Obtain a detailed history from all involved including the child, parents, caregivers, and any witnesses. Document details of the onset and progression of symptoms leading to the ED visit. Especially in young infants, pinpoint the last time the child was completely well. In a critically ill child, provide immediate resuscitation. In most cases of accidental injury, there is a clear and consistent history of an accident with the child presenting for care soon afterward. Historical features concerning for abuse include no history of trauma, changing important details of the history, explanations inconsistent with the injury or with the developmental stage of the child, discrepancies in the history provided by different caregivers, or a significant delay in seeking care.8,9,10

Obtain past medical history including the birth history, chronic or congenital conditions, previous injuries, and previous hospitalizations and surgeries. Document any family history of bleeding or bone disorders and any relevant metabolic or genetic conditions. Review the diet and medication history including vitamin K at birth and any subsequent vitamin or nutritional supplementation. Note current developmental status and progress. Important social history should identify the primary caregiver and other caregivers, household composition, any history of past abuse to the child or siblings, and previous child protective services involvement.

Begin with a general assessment of the child’s alertness and demeanor. A brief evaluation of the work of breathing, cardiovascular perfusion, and level of alertness will identify a critically ill child in need of resuscitation. Note whether there is spontaneous and symmetric movement of the extremities. Lack of use of an extremity or pain with examination or movement may indicate a fracture. Document the head circumference and examine the scalp, noting any hematomas or step-offs, which may indicate a skull fracture. Funduscopic exam may reveal retinal hemorrhages, although it is often very difficult to perform an undilated exam in a child. Injuries to the mouth, such as a torn frenulum, may be indicative of forced feeding. Fully expose the skin and document the precise location, size, and shape of any bruises, burns, bite marks, or scars. Palpate the chest, abdomen, spine, and extremities for any tenderness. Perform and document a neurologic examination if there is concern for head trauma.

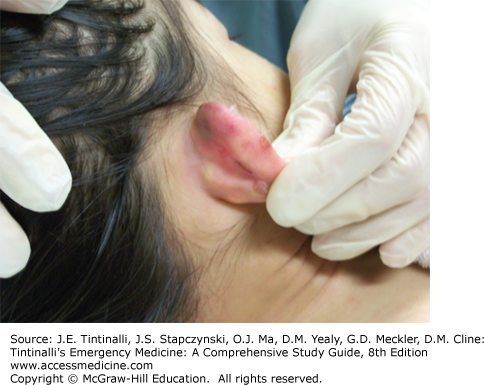

Bruising is the most common manifestation of physical abuse and is often overlooked. Up to a third of children with fatal or near-fatal abusive injuries have previous medical assessments in which bruising was noted.11,12 Because bruising is also very common in nonabused children, distinguishing between nonaccidental and accidental bruising requires careful consideration of the child’s age and developmental level, the history, and any other associated injuries. Accidental bruises occur on the front of the body over bony prominences, on the extremities, and on the forehead.13 Nonaccidental bruises, on the other hand, are more commonly found on the torso, neck, and ears (Figure 148-1) and the soft parts of the body such as the cheeks and the buttocks. Nonaccidental bruises are also more likely than accidental bruises to be found in clusters, to be on the back of the body, and to be symmetrical. In addition, nonaccidental bruises tend to be larger and more numerous than accidental bruises. Patterned bruises may be evident if a child has been struck with a hand or an implement (Figure 148-2). Although the presence of bruises of different colors was previously thought to indicate bruises of different ages, the dating of bruises is highly inaccurate, so document bruise description and do not attempt to date the bruises.14

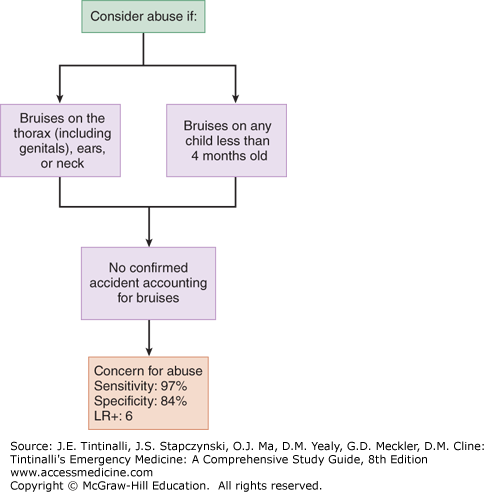

Bruises in young infants deserve special consideration because infants very rarely sustain accidental bruises. The adage those who don’t cruise rarely bruise is supported by the observation of bruising in only 0.6% of infants less than 6 months of age and in only 2.2% of infants not yet able to walk, while bruising is present in over half of toddlers.15 Bruising in infants is associated with more serious abusive injuries. Additional injuries are diagnosed in up to one half of infants with isolated bruising.16 The TEN-4 bruising clinical decision rule identifies bruises to the thorax, ears, and neck, as well as any bruising in infants less than 4 months, as particularly concerning for abuse (Figure 148-3).17

The differential diagnosis of bruises includes skin conditions such as congenital dermal melanocytosis (Mongolian spots) and cultural practices such as cupping and coining. A number of medical conditions are associated with bruising, the most common of which is idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Inherited factor deficiencies such as hemophilia and von Willebrand’s disease predispose children to bruising from inconsequential trauma. Other medical conditions include infections (e.g., meningococcemia), leukemia, nutritional deficiencies, and Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

Burns account for 6% to 20% of abusive injuries. Most burns, both accidental and abusive, are scalds and affect children age 1 to 4 years old.18 Accidental scalds typically occur when young children pull hot beverages off tables or stovetops, spilling the hot liquid onto themselves. The resulting burns are generally asymmetric, have irregular borders, are of varying depth, and are distributed over the face, neck, and upper torso.18 In contrast, most inflicted burns are caused by immersion in hot tap water.18 Abusive burns are often in a glove and stocking distribution with a sharp line of demarcation between the burned and uninjured skin. The child may have been held seated in a tub of hot water, resulting in burns to the perineum and feet with doughnut shaped sparing of the buttocks where the skin was in contact with the cooler porcelain of the tub.

When assessing nonscald burns, consider the distribution and extent of the burn. Children usually burn themselves when they reach out and touch a hot object. Most accidental burns, therefore, occur on the palms and the fingers and have an indistinct contour. In contrast, inflicted burns tend to be on the dorsal surface of the hands and on the back of the body. The margins of inflicted burns are often more distinct and may take the shape of the heated object used to inflict the burn.18

Burns due to neglect are nine times more common than inflicted burns.19 Even when a burn itself does not appear inflicted, it is important to consider whether lack of adult supervision or exposure to an unsafe environment or substances played a role in the injury. The differential diagnosis of burns includes bullous impetigo, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and severe diaper dermatitis.

Fractures are the second most common manifestation of physical abuse. Over 80% of abusive fractures occur in children less than 18 months of age, and 12% to 20% of fractures in infants and toddlers are caused by physical abuse.20,21 Because fractures are also very common accidental injuries, accounting for between 8% and 12% of all pediatric injuries, distinguishing between accidental and abusive fractures can be challenging, particularly when the caregiver may not provide an accurate history.8,22 In children <3 years old, up to 20% of abusive fractures were initially attributed to accidents or other causes.23 Children with abusive fractures may present with nonspecific complaints such as irritability, swelling, not using a limb, or refusal to weight bear. Fractures may also be discovered incidentally during evaluation for other conditions or injuries.

There are a number of historical and clinical factors associated with an increased likelihood of physical abuse; however, the single most important risk factor for abusive fractures is young age (Table 148-3).22 It is very unusual for nonmobile infants to sustain fractures.21,22 Abuse accounts for one in two femur fractures in children less than 1 year of age, whereas the likelihood of abuse as a cause of femur fractures in 2- to 3-year-olds drops to less than one in five.22,23,24,25,26

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree