Psychological Effects of the BCN Threat: Introduction

Our understanding of the psychological effects of BCN terrorism events is limited, but extrapolation from these few episodes can help us better prepare for such events in the future. What has been found from studying the effects of terrorist acts is that reactions follow those seen in other traumatic events, such as natural disasters. Recommendations and likely clinical effects are largely extrapolated from these more “usual” disaster scenarios.

Based on studies prior to September 11, primary care providers are said to manage roughly 70% of all mental health problems in the United States and that upward of 75% of all patient visits to physicians’ offices have significant or primarily psychological issues. These statistics are particularly relevant in the context of BCN terrorism. Following the September 11 terrorist attacks, a survey of primary care physicians found that nearly 80% identified terrorism-related psychosocial complaints in their patients, particularly in those areas geographically close to where the events transpired. The psychological fallout from traumatic events typically exceeds the medical consequences, in some instances by an order of magnitude. Following the 1995 Tokyo subway sarin attack, for example, 80% of those seeking medical care had no exposure to the gas. This phenomenon is seen commonly with any perceived public health or nonmedical emergency as well. During the 2003 SARS epidemic in Toronto, nearly 200 individuals sought medical evaluation for every diagnosed case of SARS. Clinicians should anticipate that anxiety and fear will result in a large number of individuals seeking care from the medical, hospital, and public health community following major disasters, public health emergencies, and of course, terrorist attacks. Although the majority of survivors experience only mild reactions, and recover fully, as many as a third may meet the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for anxiety, depression, or PTSD (see Table 7–3).

Increased anxiety in the context of bioterrorism may be explained by risk perception theory. Risk perception theory suggests that risks that are voluntary, controllable, distributed fairly, imposed from a known or trusted source, have the potential to benefit others, or are familiar or even natural, are handled with far greater aplomb. The willingness of American soldiers to climb the cliffs at Normandy in the face of Nazi guns, or a patient participating in a clinical trial of a new cancer drug, might be understood in light of this theory of risk perception. In contrast, BCN terrorist attacks are involuntary, imposed in the time, place, and manner chosen by an unknown, unfamiliar, or threatening source, have no goal other than harm, are not equitably distributed, and may involve the stuff of Hollywood movies such as unseen microbes, chemicals, or nuclear material. The very nature of terrorism amplifies the perception of risk and thereby influences greatly both individual or a community response to the event.

The BCN agents discussed in this book are all plausible and potentially dangerous threats. Creating a climate of anxiety and fear may be even more effective as a weapon of terror. Fear and anxiety regarding the use of such weapons or of other attacks since September 11 have become a part of our individual and collective psyche. This fear is neither unwarranted nor inappropriate, but it is a double-edged sword in the fact that while making us more appropriately vigilant and cautious, it creates anxiety, higher stress levels, and ethnic and religious distrust as well.

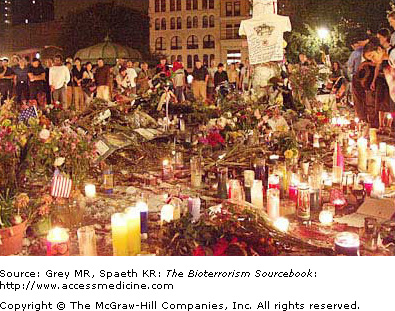

Fear is not the only consideration. The events of September 11 were traumatic for those who survived and for many who watched the events from a safe distance—the death and destruction now immortalized on video and in our memories. For many, the post office anthrax attacks had similar effects, particularly coming on the heels of September 11. PTSD affected many in the wake of these events and would surely affect many more should another event occur. Given all this, it is incumbent on clinicians to be prepared for how to deal appropriately with a spectrum of psychological issues that could result from a similar trauma in the future.

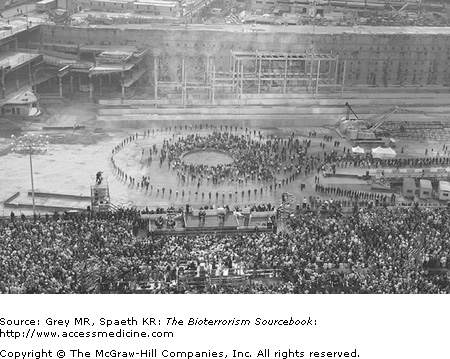

PTSD is frequently seen in those immediately affected by any traumatic event and in those who identify with the event or its victims. Millions of Americans felt (and continue to feel) that they too were victims of the September 11 attacks, whether a few miles or a few thousand miles away. Numerous studies after September 11 demonstrate a rise both in PTSD features and overall psychological stress in Americans. Not surprisingly psychic distress appears to increase with increasing proximity to the attack sites. In the six months following the WTC and Pentagon attacks, the nation experienced a significantly elevated perception of risk and immanency regarding future attacks, as well as the likelihood of themselves or loved ones being victims of an attack. Such findings were independent of both physical proximity and personal connection to the attacks that occurred in New York city, Washington, DC, and elsewhere. Though no attacks have occurred since the anthrax attacks of 2001, the psychological impact persists: bioterrorism has sensitized us as a nation. Upgrades in the homeland defense advisory system, flights cancelled or rerouted, suspicious packages, powders, and letters causing evacuations all make the headlines on a regular basis and contribute to an already elevated level of psychic distress. Not uncommonly, any major accident (e.g., power outages, plane crashes, industrial accidents) or new infectious diseases (e.g., SARS) once presumed to be accidental or coincidental in origin is now assumed at first to be a terrorist event. The uncertainty with which we now live has direct psychosocial effects and is a powerful reminder of the lingering effects of terrorist actions.

Although the emphasis of this book is on diagnosing and treating the patient exposed to one of these weapons, it should not be interpreted to mean that these are the only patients affected, or that only physical signs and symptoms result. Because of post-September 11 tensions, if there should be another such attack, significant numbers of patients will seek care from their doctors without having been exposed to BCN weapons. Some will seek counsel about protective and preventive measures to keep themselves and their families safe, whereas others will be concerned about possible exposures. In both cases, educating your patients regarding the likelihood of events or the actual risks, helpful steps, and precautions will likely be of great benefit. Hopefully, information contained in this book can be a resource for clinicians. Additional resources to address psychological consequences of BCN terrorism are provided in the bibliography at the end of The Bioterrorism Sourcebook.