Introduction to Terrorism and Bioterrorism: Introduction

The modern understanding of the word “terror” dates from the Reign of Terror following the French Revolution of 1789. One of the key figures in the Revolutionary Council—the governing body responsible for thousands of deaths by guillotine—was Maximilien Robespierre (1758–1794). Robespierre’s observation that “Terror is nothing more than justice, prompt, severe, inflexible; it is therefore an emanation of virtue” rings familiar to anyone who has read or listened to the righteous rhetoric of terrorist organizations, be they Islamic militant groups, the Protestant and Catholic factions in Northern Ireland’s civil strife, or even in the words of homegrown terrorists like Timothy McVeigh. There are numerous examples that fit this definition of terrorism throughout both modern and ancient history.

The United States has had its share of actions that meet a modern view of terrorism. Whether one is speaking of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln in 1866, or the 1998 bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma City, terrorism may reflect homegrown conflicting worldviews as well as imported ones. As the 20th century drew to a close, religious justification for terrorism emerged across the globe and in widely different societies and cultures—from Northern Ireland to Africa, from Indonesia to the Middle East. Throughout human history, terrorism has been employed by religious, political, and ideologically driven individuals, organizations, or governments to communicate their agenda, their resolve, and their capacity to disrupt life as usual.

One definition of terrorism is the deliberate, planned violent act whose purpose is to cause injury or sow fear to achieve political, religious, or ideological objectives. According to the New York Times, “terrorism seeks to hurt a few people and to scare a lot of people in order to make a point” in contrast to traditional warfare whose purpose is to conquer territory and capture cities (January 6, 2000). Terrorism may take the form of individual or state-sponsored terrorism but in all instances maintains these characteristics. When we talk about terrorism in the modern sense, we are usually referring to acts that target individuals, organizations, or governments.

In 1992, Francis Fukuyama, then Deputy Director of Policy Planning for the State Department, declared that the fall of the Soviet Empire was the final event marking the coronation of Western liberal democracy. The world, he argued, had fully and finally been delivered. The title of his book on the subject summed up this view: The End of History. At the time, it seemed a possibility: our enemy had been defeated and the new world order was at hand. On September 11, 2001, this comforting view shattered.

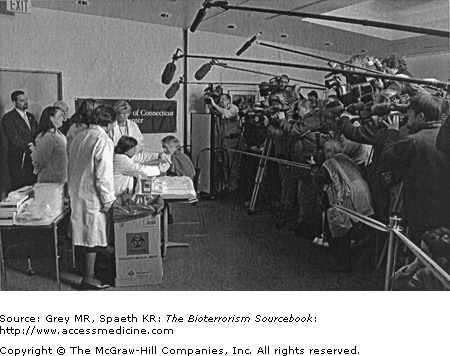

Instead, a new world enemy has been ordained, a different type of enemy: different worldview, different culture, different means. This enemy is unfamiliar, elusive, without institutions or uniforms or clear structure, and it wages its violence in unconventional ways; among these are thought to be biological, chemical, and nuclear (BCN) weapons. The existence and threat of such weapons became etched into the public consciousness beginning with the index case of the post-September 11 anthrax attacks in October 2001 and became injected indelibly into it with the first administrations of smallpox vaccine that began with four physicians at the University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, Connecticut, in January 2003 (Fig. 1–1). Although the intensity of our nation’s focus on and concern with terrorism waxes and wanes—driven by media stories or changes in the alert level issued by the Homeland Security Agency from yellow and back again—underneath these oscillations is a vigilance that would have been inconceivable only a few short years ago.

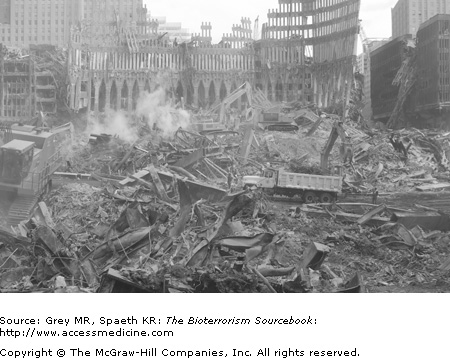

Experts typically summarize three general categories of weapons of terror: weapons of mass destruction (WMD), weapons of mass casualty, and weapons of mass disruption. WMDs are devices—such as missiles or bombs—that are capable of inflicting serious damage to infrastructure, for example, buildings, bridges, or dams. In contrast, biologic, chemical, and radiological agents are viewed as weapons of mass casualty because they may result in widespread disease, debility, or death. Weapons of mass disruption are devices or strategies intended to inflict social, political, or economic injury on a targeted group, organization, or society. Examples of the latter are poisoning or contamination of agricultural supplies or food manufacturing systems (agroterrorism), or cyberterrorism, where vital systems are disrupted or critical records are destroyed by computer hackers. These three categories are by no means mutually exclusive as the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center (WTC) and Pentagon made all too clear. In each instance, the terrorists destroyed nationally prominent buildings, killed over 3,000 persons, and inflicted profound and lingering social, political, and economic disruption of American society from which it is still recovering (Fig. 1–2).

Much can be and has been written about the methods by which these deliberate attacks occur. Nevertheless, experts tell us that the terrorist’s overarching desire is to injure or kill, destroy objects or infrastructure, or otherwise disrupt the normal routine of society, whereas the mechanism of achieving these outcomes is less important. An obvious corollary of this is that terrorists are free to use unconventional or unexpected means intended to surprise their chosen target. Terrorists can often use their numeric, logistic, and technologic inferiority to achieve a tactical or strategic advantage leading some experts to refer to terrorism as “asymmetric warfare.” That is, a confrontation between an “enemy” whose resources are unequal to their opponent and thus use apparently random acts of violence in order to communicate political, religious, or ideological objectives to the rest of the world. This point was made quite explicit in then Secretary of Defense William Cohen’s Annual Defense Report to the President and the Congress in 1998. In it, Cohen acknowledged that asymmetric warfare offered strategic advantages for terrorists in their efforts to gain a tactical advantage. “Those who oppose the United States,” wrote Cohen, “will increasingly rely on unconventional strategies and tactics to offset U.S. superiority, such as biological or chemical weapons.”

Biological, Chemical, and Nuclear Terrorism: Present Realities and Concerns

Even before September 11, 2001, the federal government was preparing with relatively little fanfare for the possibility of BCN terrorism within the nation’s borders. As part of this preparation, Congress passed legislation requiring the Justice Department’s Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to conduct field tests of our crisis response systems. One of these field tests, referred to as TOPOFF 1, took place in the city of Denver, Colorado, on May 17, 2000, at a cost of approximately $3 million. A brief review of this real-time simulation of our preparedness for bioterrorism is both instructive and sobering.

Denver was considered an optimal location to run the TOPOFF experiment because this particular region of the country had received significant funding and training in disaster management over the years due, in part, to the substantial military presence in the state. The biological agent chosen was Yersinia pestis, the causative agent for plague. The combined resources of local, state, and federal health and law enforcement officials as well as local law enforcement agencies were brought to bear following the mock release of plague. Although some members of Congress were debriefed on the TOPOFF 1 trial, for reasons that will become clear, details were kept from the media and the public for quite some time. While many aspects of the test are worth commenting on, a few will serve to highlight lessons learned as a result of the TOPOFF test and exemplify the larger issues that The Bioterrorism Sourcebook is intended to address.