Environmental Terrorism: Introduction

Terrorist activities in the United States and abroad have heightened our awareness of the vulnerability of specific aspects of our communities and economy to BCN threats. For example, the possibility exists that terrorists could target water supplies and agricultural livestock, or release agents into ventilation systems in such a way as to disperse a BCN agent. This concern is neither speculation nor the result of theoretical vulnerability analysis; documents found by U.S. troops hunting down al Qaeda members in their mountainous hideouts in Afghanistan suggest that agroterrorism is a plausible terrorist scenario. While searching one such al Qaeda hideout, the U.S. military came across Arabic translations of hundreds of pages of U.S. governmental agricultural documents. Osama bin Laden, himself, has significant training in agricultural methods from his background with various agricultural businesses while in the Sudan. Furthermore, it has been well documented that the September 11 hijackers made efforts to get hold of a crop duster while in Florida. Crop dusters could certainly serve as a simple but effective means of distributing crop, livestock, and human disease or chemical contamination (Fig. 4–1). Al Qaeda has made no secret that it is their intention to cripple the U.S. economy, so targeting of a major component of the U.S. economy certainly has, at the very least, crossed their minds.

Drinking Water Security

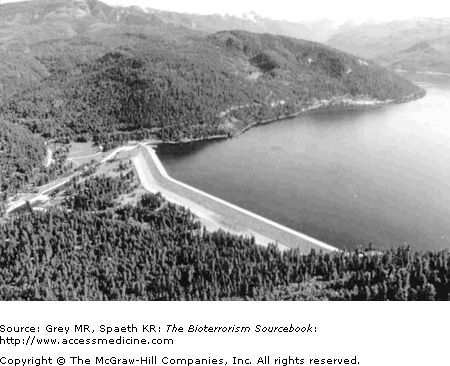

The nation’s water supply system is comprised of an elaborate and multifaceted system involving public, private, and quasipublic entities that manage and maintain our water supply to serve industry, agriculture, municipalities, and the general population. The water system infrastructure is composed of four basic components: water sources (in the form of lakes and ponds), water treatment, storage, and distribution. Sources of water include rainwater, underground springs, or surface water reservoirs that are usually dammed by an earth, concrete, or masonry structure and that collect water through stream or surface run off. There are roughly 75,000 dams and reservoirs nationwide.

Water treatment is accomplished in a variety of ways, ranging from no treatment to basic treatment (e.g., chlorination, adjustment of pH, iron removal) to more complex systems where filtration and chemical treatment of surface water exist. Following treatment, water is stored in containment facilities, such as reservoirs, storage tanks, and water towers. From this point, water is distributed through progressively smaller conduits to consumers involving thousands of miles of pipe. Distribution systems include pumping stations, and large water mains running from the source or storage area to increasingly smaller pipes and ultimately ending up at hydrants or the kitchen tap. The complexities of such a system make it vulnerable to acts of terrorism at virtually any point.

The EPA is the primary federal agency responsible for protecting the nation’s water supply. The 2001 Bioterrorism Act mandates that water utilities conduct vulnerability assessments and create emergency response plans. As part of this assessment, critical system components must be identified and procedures to prevent or respond to sabotage must be developed. Certain considerations make the water supplies a possible target; for instance, 75% of the population is provided water from 15% of national water systems. Consequently, a few key facilities vital to a majority of the population are more likely targets. But even an attack on a smaller site would have tremendous psychological and logistical consequences.

Water sources often encompass a wide land area, a fact that complicates security considerations (Fig. 4–2). As a practical matter, protecting a community’s water supply, like all of BCN terrorism, is a cooperative effort. The combined resources of local, state, and federal law enforcement, emergency response systems, the medical community, intelligence agencies, and to no small degree, the general public must all be engaged in securing our communities’ water systems. Water companies have well-defined response plans to assess potential bioterrorist situations, identify any breaches in security and safety of the water supply, and act accordingly; nonetheless, they are asking the public to maintain vigilance around water supply sources. Suspicious activity—such as unauthorized individuals or vehicles in the vicinity of any drinking water supply source, dam, or gatehouses—must be reported immediately to local law enforcement, and, in most states, local or state public health officials. Individuals should not intercede when they observe suspicious activity; rather, they should notify local law enforcement or call 911.

Terrorists need not inflict illness to sow terror in our communities. The mere presence of a contaminant, even without its ever causing illness would likely cause widespread anxiety. Disruption of water service by tampering (whether genuine or faked), introducing contaminants, conventional attacks on dam or facilities, all would cause widespread concern or even panic. Another consideration is the possibility of cyber attacks on complex water treatment facilities’ computer systems, which could cause disruption of water distribution for days. The impact on any of these scenarios on communities would be enormous, logistically, economically, and psychologically. Hardest hit would be urban areas and communities most dependent on public water systems.

The nature of the water treatment is such that, with the exception of Cryptosporidium parvum, it is unlikely that most biological agents would survive usual disinfection practices. However, treatment methods are not foolproof. Sabotage of treatment systems combined with contamination could occur. The other end of the spectrum, those communities with little to no treatment at all, are obviously more vulnerable to a one-strike bioterrorist attack. It is worth reemphasizing the reassuring fact that contaminating a water supply on a scale that could affect large numbers of people would require prohibitively large amounts of contaminants and comparable logistical and technical resources. A threat of this nature at such a scale is improbable, but not impossible.

Table 4–1 provides examples of biological agents that could be used to contaminate water supplies. Readers should remember that chemical and radiological agents could be used as well. With these, too, they need not necessarily inflict health injury as their mere presence would have a ripple effect within the community, disrupting usual activities dependent on the presumption of safe water.

| Vibrio cholerae |

| Campylobacter |

| Yersinia enterocolitica |

| Legionella pneumophila |

| Salmonella spp |

| Shigella spp |

| Escherichia coli (EHEC) |

| Rotavirus |

| Norwalk/Norwalk-like Hepatitis A |

| Isospora belli |

| Cryptosporidium parvum |

| Cyclospora cayetanensis |

| Microsporidia |

| Giardia lamblia |

| Entamoeba histolytica |

April 1993, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Following an inordinate number of reports of debilitating gastrointestinal illness in the area, it was discovered that in April 1993, one of the two primary water treatment facilities in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, was malfunctioning and inadequately filtering the water supplied to residences and businesses in the area. In the weeks that followed, it is estimated that over 400,000 people developed diarrhea. This is thought to be an underestimate. Over one hundred people died. The largest waterborne epidemic in the history of the United States had just occurred. The water samples revealed that while levels of the most waterborne pathogens remained stable, there was a one hundred-fold increase in cryptosporidium in the water. Although the failure of the water treatment process was purely accidental, it does suggest the potential morbidity and mortality that could result from sabotaging of water treatment facilities. Although it may be more sensational, a bioterrorist attack with a waterborne pathogen would likely affect far fewer people than a strategic sabotage of a water treatment plant might.

It is significant, too, that, no warning from the monitoring system at the facility indicated the problem. Instead, contamination was discovered after an observant local pharmacist noticed a boom in the purchase of antidiarrheal products. He contacted authorities and an investigation was begun. This episode underscores underappreciated but creative opportunities to develop surveillance systems for bioterrorism (see Chapter 5).

Indoor Air and Ventilation Systems Security

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree