An Overview of Homeland Security, Public Health, and Emergency Preparedness

In the post-September 11 world, clinicians need a basic understanding of the national homeland and public health security structure. Fundamentally there are two major areas of responsibility in the event of any emergency: crisis management and consequence management. In 1995, President Clinton signed Presidential Decision Directive 39 (PDD 39), the purpose of which was to define agency-specific responsibilities during an emergency. PDD 39 delegates crisis management authority—defined as overall control of the local, state, or national response to a bioterrorism event—to the law enforcement community. In the event of a terrorist attack, any and all criminal investigations would be controlled by the Department of Justice, specifically the FBI. PDD 39 assigns responsibility for consequence management—defined as the public health and safety issues resulting from a terrorist attack—to FEMA. In this organizational structure, health care and public health are the jurisdiction of FEMA.

The demands of law enforcement and the public health responsibilities are not mutually exclusive domains. That being said, it is important to acknowledge that historically these two communities have very different missions and culture. These differences cannot help but influence how each arm of the nation’s security system will react in the event of an emergency. Recognizing these distinctions has relevance in the context of emergency preparedness and emergency response. The nation’s preparedness efforts have included a great deal of cross-institutional community building in recognition of this fact.

An important example of an outgrowth of PDD 39 is the creation by the CDC of the Health Alert Network (HAN). The HAN is a dedicated CDC-sponsored website where state and local health directors may view securely posted documents, submit or collect data, obtain town- and district-specific aggregate data, enter planned absences, e-mail, or view a bulletin board. The overall goal of the HAN is to securely facilitate communication of critical health, epidemiological, and bioterrorism-related information on a 24/7 basis to local health departments, health organizations, clinicians, and other organizations with a vested interest in staying abreast of developments with potential public health implications. As a nationwide service, the HAN can disseminate late-breaking, updated, or new public health information. The HAN is intended to rapidly alert local health departments, public health officials, and the medical community to any issues that may impact the public’s health. It also offers educational and training programs for public health and medical professionals. The HAN should improve communication between state and local health agencies, departments, and care providers for better coordination of knowledge, information, and practices in the event of an emergency of any variety. For example, it was widely and effectively used during the 2003 international SARS epidemic. The nation’s public health response to SARS is a fine example of the “dual use” approach to bioterrorism preparedness and planning. Simply defined, broadening and strengthening the nation’s public health infrastructure and resources—spurred at least in part by September 11th and the anthrax attacks—provides public health benefits well beyond bioterrorism. This system played a direct role in limiting the impact of a new global health threat in this country and should improve still further in the future. The SARS epidemic was one of the first truly national field tests of the nation’s preparedness effort, and the response was widely considered a successful one. Currently, the HAN system provides public health information to over a million individuals across the country. According to the CDC, most states have HAN systems in place covering over 90% of their population. The HAN website is not encrypted, so that at the present time confidential data are not entered through this portal. It is an excellent resource for community physicians and other health care providers. Access to the HAN is through the website maintained by the CDC (http://www2a.cdc.gov/han/Index.asp).

In 1999, Congress gave the CDC formal responsibility to expand and improve the readiness of the nation’s public health workforce and infrastructure to respond to a bioterrorist attack. CDC’s Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Office addresses the full breadth of preparedness issues, from biological to chemical to nuclear agents. This includes medical therapeutics stockpiling, enhanced communication, rapid laboratory diagnostic capacity, improved surveillance, and augmented state and national epidemiologic capacity and emergency planning. One of the important outcomes from such efforts is the risk stratification of the potential biological weapons into Categories A, B, or C. These categories have become the frame of reference for medical and even political discourse in regards to biological weapons. Needless to say, these categories play a central role in the organization and discussion of biological weapons in this text.

Since 2001, Congress has passed a series of legislative initiatives, all aimed at improving state and local emergency preparedness, public health infrastructure maintenance and expansion, public health workforce development, and outreach and education. Billions of dollars have been directed to this effort. Timetables and metrics were deliberately kept short in order to ramp up the nation’s public health system rapidly. A major driver in state and local public health preparedness has been the CDC’s Public Health and Preparedness Bioterrorism Cooperative Agreement. Funding through the CDC Cooperative Agreement has been directed to a wide range of activities. For example, states and local public health departments have 24/7 access to several rapid communications networks. One of the most accessible is the HAN. Other developments that have the potential to facilitate the nation’s preparedness efforts are the Wide Area Notification System (WANS) and the Medical Satellite (MEDSAT) program. The WANS is a telephonic system with autodialing and voice messaging capabilities. It allows 24/7 notification of key components of the emergency response, law enforcement, medical, and public health community via landline phones, cell phones, pagers, faxes, and e-mail. The goal of the MEDSAT program is to enhance the emergency communications capacity for departments of public health and their key public health emergency response partners. The MEDSAT program provides a highly reliable telephone connection to be used in response to a public health emergency or in the event of a localized or catastrophic failure of the conventional telephone network.

The Strategic National Stockpile (SNS), formerly known as the National Pharmaceutical Stockpile (NPS), is another national initiative coordinated by the CDC and one with which clinicians should be familiar. The purpose of the SNS is to meet the acute vaccination, prophylactic, and medical management needs in the event of a bioterrorist attack. The stockpile includes vaccines, antibiotics, medical supplies, and medical equipment. These resources are maintained at strategic locations throughout the country and are available for immediate delivery. The locales of the sites are known only by CDC officials. The SNS is structured such that it is perpetually in a state of readiness should a biological or chemical attack occur in the population. The supplies are packaged so that no specific request need be made; rather, a request for any particular item elicits a delivery of a prepackaged armamentarium of treatment and protection. The designated term is a “12-hour Push Package,” reflecting the CDC’s commitment to have them available in less than twelve hours following an event, and it “pushes” any possible supplies needed regardless of the specific agent involved. Existing plans call not only for the delivery of the “push packages,” but also for a rapidly mobilizable a team of CDC advisors to help states and municipalities respond to a crisis. The CDC is currently distributing “Chem-Packs” in much the same manner. What began as a pilot project in 2003 is now a fully developed $30 million a year strategy to distribute preassembled packages of available chemical antidotes to states and municipalities for use in case of an attack involving chemical agents. Each Chem-Pack is thought to be capable of treating up to 1,000 people. Like the Push Packages, the CDC plan allows for Chem-Packs to arrive at an event site anywhere within the United States within a twelve-hour period.

Emergency Response Systems and Incident Command: Problems and Promise

The September 11 attacks on the WTC and Pentagon highlighted the inadequacies of the existing incident command systems in the United States. Hundreds of first responders and health care workers who came to Ground Zero worked long hours with wholly inadequate safety measures. Coordination was lacking, so that even when PPE was made accessible, knowledge of its availability and whereabouts too often did not translate down to those who could have distributed it to the men and women working in the smoking and pulverized debris.

Further, when PPE was donned, it was often used improperly and therefore not protective. Consequently, hundreds of firefighters, police, ironworkers, and other emergency responders found their unselfish efforts rewarded with medical problems that have, in many instances, continued to plague them. Indeed, thousands have since been enrolled in federally funded cohort studies to better define the health consequences of this unique national trauma. The largest and most prominent of these is the WTC Health Registry, designed as a prospective longitudinal cohort. A study of the health effects of individuals exposed to Ground Zero in the early hours and subsequent days following that trauma. Currently there are some 50,000 enrolled workers in the WTC Health Registry.

Sadly there were some at the time who espoused the opinion that anyone who had the temerity to raise health and safety issues during such a catastrophe was, at best, unpatriotic. Now that the dust has truly settled and the trauma is less immediate, it is evident that those who raised such concerns had the best interests of the heroic men and women at heart. Further, the experience of September 11 has provoked important attitudinal shifts within the emergency response community itself: emergency response and disaster management planning must integrate health and safety awareness into both training and preparedness efforts in order to protect those who are called on in such an event. Bravery should not require foolhardiness, or unnecessary or inappropriate risk taking, regardless of the circumstances. Further, emergency responders who become either injured or sick unnecessarily due to inadequate advance training, use of protective strategies, and the like are unable to do their jobs. In this instance, the emergency and public health response suffers along with that of the individual workers.

Incident Command Systems

The ICS model has been adopted to address the critical need for a formally organized and trained disaster management structure that can be called on in a crisis. The ICS is a planned system that provides for the development of a complete emergency management organization, whether comprising a single agency or optima agencies. The ICS can function as a bridge that connects resources outside of a community to those within a community in order to respond to temporary but overwhelming demands. Although the ICS provides a predictable chain of crisis management, it does so without sacrificing flexibility in terms of tasks and responsibilities and scale of effort. In addition, the ICS affords the opportunity to prioritize responses and accountability, and by streamlining and clarifying roles and responsibilities, it should prove to be a cost-effective management strategy. Clearly, advance planning and training of the ICS in any community or state or region is critical to providing the sort of experience needed in an emergency. Put bluntly, emergency planning with health care providers and public health systems needs to be accomplished prior to an emergency and practiced in order to have confidence that it will do what it was intended to do in an emergency. An effective ICS also allows for the overall coordination of containment, decontamination, patient triage, surveillance, and immunization efforts. These are addressed in more detail later in this chapter.

At the state level, there are fairly well-delineated crisis and consequence management teams in place. Training and advance preparation teams will respond to a crisis as planned, but neither field tests, nor table-top exercises are the same as the real thing. As noted in Chapter 1, the TOPOFF trials have highlighted the significant obstacles that even well-prepared crisis management and consequence management teams will find difficult to navigate. The reasons are many. First, each incident has its unique features and idiosyncrasies that complicate advanced planning and real-time response. Second, the emergency management response requires significant interactions with ordinary citizens whose diverse reactions will make an ordered response more difficult. Often communication systems are swamped by the sheer volume of information and traffic that they are being asked to carry, a circumstance that makes already confusing situations even more chaotic. Individuals trained to respond are themselves under enormous physical and emotional stress, and relationships that work well in a field exercise might deteriorate quickly during an acute event. The pace, intensity, and confusion of a true disaster often confuse lines of authority and hinder clear task assignment. Finally, as the nation observed during the first horrifying hours after the WTC collapse, safety practices and training may be inadequate to the task, thereby increasing the risk to those individuals who are putting their lives on the line.

The initial response to any emergency or disaster comes from local first response systems and hazardous materials (Hazmat) teams. The incident commander is, in fact, typically the local fire chief. Local agencies or the ICS commander notifies the state health department. State health departments have teams trained to respond quickly to any emergency and conduct onsite environmental monitoring in order to determine what, if any, chemical or radiation hazards exist. Regional response teams have been assembled throughout the country, allowing shared expertise. This is critical for bioterrorism as few communities have direct experience with BCN events. For example, these regional response teams have both state-based radiation experts and radiation safety experts from the Department of Energy to assist local and state officials in dealing with a radiation incident.

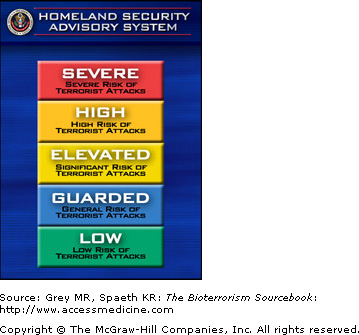

As noted earlier, FEMA is the overall lead nationally for managing the medical, public health, and logistical aspects following a bioterrorism event. President Bush has designed the Department of Homeland Security as the lead agency for coordinating the crisis and consequence management for all bioterrorism events. The Homeland Security Department supervises the FBI in its criminal investigations and FEMA in its public health management. These systems have yet to be fully tested in a true crisis, although table-top and field exercises have simulated disasters as a means of training and testing the preparedness systems at the local and state levels.

Surveillance is a key aspect of the ICS. This can take more than one form, including monitoring of water or air for chemicals, biologics, or radiation or surveillance for medical syndromes that could be a clue to a release. Identification of resources that would be needed to respond in a timely and appropriate way to the event is yet another task. This includes defining those individuals, institutions, or organizations that will participate in the emergency response and exactly what their roles will be. In the setting of a significant public health emergency, this includes local medical, public health, first response, and law enforcement resources. Choosing the proper response to the specific event is an important task of the ICS as well. During crises, timeliness and efficiency are crucial in order to limit as much as possible social, economic, and health consequences. Finally, the ICS is responsible in many communities for establishing training programs to prepare the community for such an event. These key responsibilities are summarized in Table 3–1.

| Identify sources of exposure and potential threats |

| Identify routes of spread and exposure from threat or event |

| Establish surveillance mechanisms |

| Identify resources needed to respond |

| Define the role of responders |

| Select the proper response |

| Establish training programs |

Hospital Preparedness and Emergency Response

Hospitals are critical to the nation’s preparedness efforts both in the response to disasters or bioterrorist events and as potential targets themselves. Emergency departments, intensive care units, security, and first responders will have crucial roles in any bioterrorism event. Each hospital should have a response plan in place that delineates emergency preparedness teams (EPTs). EPTs include clinical and support staff that are fully trained and whose roles are clearly defined. Hospitals should prepare institutional policies and procedures for the institutional response to issues such as mail-handling protocols; decontamination; chain of command; communication protocols; general safety and security of the institution, including locking of entrances at night and monitoring of visitors and staff; requiring all staff to have a visible identification badge with a photograph; fire and evacuation plans for the institution and communication with town and state emergency plans; discussions about radiation and biohazards safety and protocols to protect other patients and workers; mass casualty preparation and procedures; infection control institutional monitoring and reporting system to hospital epidemiologist, employee health service medical director, state department of public health, FBI, and CDC; and employee psychological support system through connections with Department of Psychiatry and Employee Assistance Program for debriefing and crisis management in the event of a bioterrorism incident.

Developing a resource binder or similar readily accessible resource where staff may review information available from the CDC, state and local health departments, the FBI, the EPA, or other sources is extremely important. A computer workstation with bookmarked key Internet sites for the most up-to-date information should be available to individuals involved in any organizational response. It is also useful to include directions for handling a suspicious package or letters, or someone bringing suspicious materials into an emergency room or office (Table 3–2). These resources will enable EPTs and other interested parties to familiarize themselves with protocols and practices prior to an event and also serve as a valuable resource in the event of an attack. It is essential that the lines of communication be very clearly delineated: who should be called, when, and for what purpose. Specimens from patients suspected of having been exposed to a bioterrorism attack are a good example of the importance of communication. Determinations of biological, chemical, or radiation exposures may require special collection techniques, and the material collected may need special storage and shipment to the CDC or other specialized laboratories. Lines of communication with the state department of public health laboratory and the CDC will be necessary in order to ensure the collection, storage, and if necessary, transport and delivery, are all done with proper attention to chain of custody, health and safety, and, of course, the testing requirements needed to ensure accuracy.

| Do not disturb, transport, or investigate package or envelope |

| Do not allow others to disturb or handle or investigate |

| If leakage has occurred, do not inspect, sniff, or touch |

| Close all doors, shut off ventilation, fans, and air conditioners |