A Brief History of Nuclear Weapons and the Atomic Age

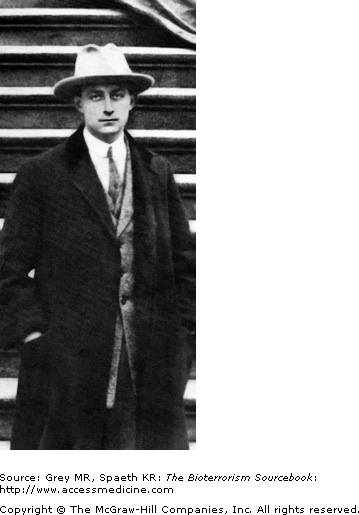

“I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

Quote from Bhagavita attributed to J. Robert Oppenheimer

“Father of the Atomic Bomb”

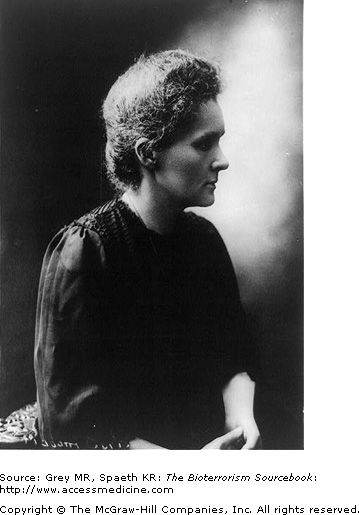

The history of the nuclear age is a series of steps—many quite small, others of medium stride, and others still veritable leaps. Discoveries such as the presence of electromagnetic forces noted by Maxwell to Roentgen’s stumbling onto the presence of x-rays, to Becquerel finding naturally occurring x-rays from uranium, to the Curies discovering the key components of are just a few examples of such steps (Fig. 27–1). From the late 19th century and into the 20th century, several important larger discoveries were made: Rutherford discovered alpha and beta particles, and Planck articulated the quantum theory of physics. During that time fundamental principles of radioactivity were being sorted out; such as isotopes, radioactive decay, and the properties of the types of radiation.

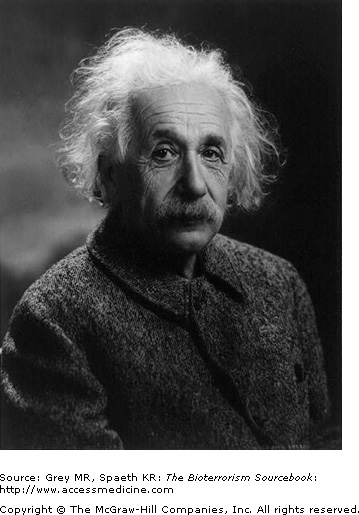

In 1905, the history of science and of the world was altered irrevocably when Albert Einstein, working full time as a patent clerk in Bern, Germany, conceived of and derived what is perhaps the most recognizable equation in history: E = mc2. Einstein’s theory of relativity had profound implications, a worthy discussion of which is beyond the scope of this text. For our purposes, the most important was its inference that enormous energy is contained in even a single atom. It was not long before the hunt to access that energy began (Fig. 27–3).

The critical breakthroughs to harnessing atomic energy came in the late 1930s. When nuclei were bombarded with slow-moving neutrons, they became unstable and split into smaller particles. However, these smaller particles added up to a weight less than that of the original nuclei. The missing mass had become energy: a vast amount of energy. The implications of this research, particularly its military potential was realized quickly in several Western nations, including Germany, England, and the United States. As the 1930s progressed, tensions between Hitler’s Germany and other European powers erupted into World War II and the work of atomic physicists worldwide became a critical resource for the war effort.

The story of the development of nuclear weapons is a fascinating and pivotal one that altered the history of the 20th-century world. During WWII, both the Nazis and the Americans raced to develop viable nuclear weapons (Fig. 27–2). Although Germans had a head start, when the allied forces forced the unconditional surrender of German forces on May 7, 1945, Nazis scientists had yet to complete their work. In the United States, the responsibility for developing an atomic weapon began with the so-called Manhattan Project. In fact, some effort to build a bomb began in late 1939, but the work has not coordinated, poorly funded, and generally lethargic. Full-fledged research began after the U.S. government heeded repeated warnings by the British government and escaped German scientists, including the world’s most famous scientist, Albert Einstein. Once the Manhattan Project was fully funded, (ultimately receiving $2 billion) and had full presidential and military backing, research progressed rapidly, facilitated by advancements made at universities and government laboratories throughout the country. Considering its late start, the Manhattan Project went quite quickly, and bomb tests were first conducted in New Mexico on July 16, 1945.