A Clinical Approach to Biological, Chemical, and Nuclear Terrorism: Introduction

The U.S. Postal Service anthrax attacks demonstrated that while diagnosing an index case of a BCN event is difficult, knowledgeable and vigilant clinicians can and do play vital roles in lessening the extent and severity of such attacks. Increased clinical vigilance results in earlier recognition and earlier intervention. Likewise, more vigilant public health efforts facilitate preventive interventions (e.g., antibiotic prophylaxis) and environmental decontamination. This in turn protects exposed workers and prevents further exposures. The clinical and public health experiences gained from the anthrax attacks serve as a valuable frame of reference for anticipating the clinical and public health needs generated by any future BCN attacks.

Certainly, an acute BCN event will activate immediately the machinery of the nation’s public health infrastructure and alert clinicians to evaluate all patients in a different way. With index cases of bioterrorism, the challenges are much greater: clinicians need to recognize BCN exposure even when it is subtle and unheralded, as with the early cases of anthrax.

Clinicians need to be able to take an appropriate history and conduct a targeted physical examination not only to ensure an index case does not get missed following a BCN event, but also to evaluate all patients with a syndrome consistent with BCN exposure following a recognized attack. A second element of clinicians’ responsibilities relates to infection control. Early and strict adherence to established infection control practices is essential to protecting health care workers and first responders, medical and ancillary staff, and secondary contacts, and to limit the spread of an epidemic. Finally, in addition to their bedside skills and awareness of infection control practices, clinicians must also be prepared to engage with both the public health and legal systems when responding to any real or potential BCN event. This chapter provides guidance to clinicians in the three essential responsibilities of clinical diagnosis, infection control, and public health intervention.

Hijackers in Florida

It is believed that one of the September 11 hijackers was seen by a Florida physician for what was initially diagnosed as a skin infection but was later (during the September 11 attack investigations) diagnosed as cutaneous anthrax. In the doctor’s defense, such a diagnosis would have been extraordinarily rare, particularly when the United States had not yet recognized the dangers to come. Nonetheless, a proper diagnosis initially may have altered history—serving to highlight the importance of properly trained and vigilant clinicians.

Taking a BCN History

Clinical vigilance in today’s geopolitical climate has become a requirement for clinicians. Barring a sentinel terrorist event that changes the clinical approach radically, BCN possibilities should be ever present, albeit hovering low and distant on differential diagnoses of appropriate clinical pictures. Such a practice is rife with challenges, particularly because the signs and symptoms of the biological and chemical agents are typically nonspecific, especially early on. This is particularly true in an unrecognized attack as the first cases will likely present with syndromes indistinguishable from more common diseases or may be nested within a normative seasonal rise in the syndrome. For example, respiratory bioterrorism syndromes may be very difficult to identify in the midst of a typical winter-time influenza epidemic.

As with the establishment of any diagnosis, a meticulous history is one of the clinician’s best tools. In the setting of biological, chemical, and to a lesser extent radiological events, history taking must be particularly thorough, even pointed at times. The purpose of the BCN history is to establish the probability of an exposure; to determine the nature of the exposure; to identify subsequent management decisions relating to treatment, decontamination, and infection control; and to dictate public health measures that may be indicated, such as postexposure prophylaxis, immunization, surveillance, or epidemiologic and possibly criminal investigations. Clearly the clinician provides a pivotal link in the recognition, management, and public health response to BCN terrorism.

The initial clinical assessment of patients with suspected exposure to BCN agents begins with a thorough history of the present illness (HPI). Soliciting details about the onset, timing, rate of progression, and nature of signs and symptoms will be essential to identifying the presenting toxidrome. Toxidromes refer to a constellation of symptoms and signs that taken together form a pattern of illness consistent with a biological or chemical event. (Chapter 5 discusses several of the most relevant and more readily recognizable toxidromes in more detail.) Recognition of a toxidrome, or including a particular BCN agent in the differential diagnosis, must necessarily guide medical management, infection control, decontamination, and public health responses (Table 2–1).

| History of present illness: Note time and location of onset, rate of progression, symptom clusters |

| Detailed past medical history: Medical conditions, medications, allergies |

| Detailed social history: |

| Memberships in organizations |

| Environmental exposures (animals, unusual foods, water sources) |

| Occupations (prominent or strategically important positions, agencies, or organizations) |

| Travel (international and domestic, tourist attractions, national monuments, or political rallies) |

| Clusters and syndromes of co-workers, family, or co-travelers with similar symptoms and time of onset, animal die-offs |

Thinking along the lines of toxidromes should be familiar to clinicians. The art of differential diagnosis in many respects begins with recognition of a pattern of symptoms or signs that suggests a particular disease or set of diagnoses. Until recently, few BCN agents would have shown up in the differential diagnosis of specific clinical syndromes even in the most rigorous of training programs. After all, prior to September 11, how many of us would have added smallpox to the differential diagnosis of a toxic-appearing patient who presents with a fever and rash? The probabilities against such a diagnosis would have been enormous. As is often the case, however, a small shift in detail or circumstance changes these probabilities entirely. To continue our smallpox example: if it was 1965 in Somalia—over a decade before the “eradication” of smallpox by the World Health Organization—one would have been negligent not to include smallpox high on the list of possible causes for a patient presenting with fever and rash. If the time and place was not 1965 in Africa, but rather 2004 in Atlanta, one would once again think smallpox was a near impossibility. But what if the stricken individual was a CDC employed laboratorian? This minor change in detail alters in important ways the differential diagnosis, including, in our example, at least two Category A agents: smallpox and viral hemorrhagic fevers. Although arguably less weighty in the probabilistic approach to differential diagnosis, the circumstances of medical and public health practice have been substantially altered by the fact that terrorists have used and may continue to use these agents as weapons to pursue their political and social agenda.

Following the HPI, clinicians should conduct a past medical history (PMH), the objective of which is to identify significant co-morbidities, medications, and allergies. Any positives from this aspect of the clinical history have the potential to impact directly on clinical decision-making. An example from the recent national smallpox vaccination campaign will suffice to make this point more concrete. Individuals with atopic dermatitis, eczema, or significant skin compromise were medically excluded from receiving the vaccinia vaccine because of the increased risk of several serious adverse events, including autoinoculation, generalized vaccinia, and eczema vaccinatum. Should a case of smallpox be diagnosed somewhere in the world, mass vaccination clinics might well be implemented. The preexisting medical conditions that would have precluded vaccination in a preevent situation might not prevent a recommendation for vaccination in the setting of a known case of smallpox; however, the clinician still needs to know the individual’s medical history in order to allow an informed decision to be made of the risks versus the benefits of receiving the vaccine.

The social history is an often-neglected component of the clinical history, but in the setting of BCN terror it assumes an unusually prominent role. The overarching objective of this component of the clinical history is to identify social, environmental, and occupational factors that may have a direct bearing on clarifying the likelihood of a BCN exposure. If an attack has occurred, then aspects of the social history have relevance from a public health perspective, identifying potential means by which an epidemic from a deliberate biological attack might progress. Some individuals may be in high-risk occupations or high-profile institutions. Government, research, military organizations, as well as mass media organizations and financial institutions come to mind. Identifying political affiliations, as well as attitudes toward certain ethnic, racial, religious, political, activist groups, organizations, or associations may also be important but should be handled delicately.

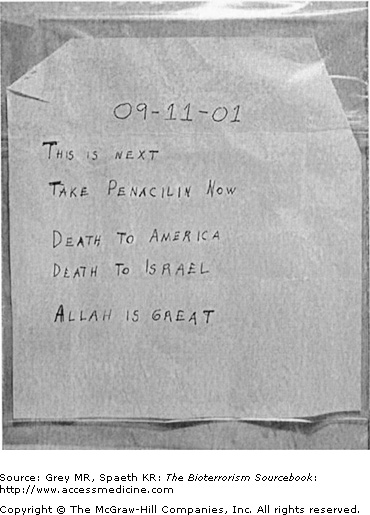

A detailed occupational history will determine if the person works in a high-risk occupation. Examples include government workers, such as post office employees, elected officials, or other governmental representatives or employees (Fig. 2–1). Military personnel; law enforcement workers, such as the FBI; and city, state, or federal employees of any capacity could be targets because they work in public facilities that are more probable targets. Certain individuals work in higher-risk locations in these industries as well; the most obvious example being mail room workers. Nongovernmental workers who may be at greater risk include individuals employed in high-profile positions in major corporations or media companies such as television, radio, or newspapers. Lower-profile positions at high-profile organizations—for example, Wall Street firms and major media outlets—could again include mail room workers. Occupations at greater risk would also include laboratory technicians, scientists and researchers, and of course, health care workers. In addition, all of these “at risk” occupations will have close contacts—spouses, children, parents, and the like—who themselves are at greater risk than the general public (Fig. 2–2).

Other components of the social history should include identifying potential exposure to animals, unusual packages or foods, recent travel, change in diet, water sources, and sick contacts. Inquiring as to whether exposure to animals—rodents, rabbits, exotic animals, or dead animals, including birds—is important since certain biological agents are zoonotic in their natural state. The person may have received strange or suspicious packages in the mail or from direct delivery sources. Imported gifts, and any correspondence or package with foreign addresses are again potential sources. Obviously exposure to sick contacts who may have a similar constellation of symptoms must be included. A dietary history should be taken to determine whether the person has ingested any unusual foods contained in cans or jars. Dietary history must also include types of food as well as food sources. Others with similar food exposures might themselves become ill or could transmit the agent to others, so determining the timing, location, and nature of eating patterns can be useful. Whether a person has been recently exposed to certain public water sources, such as in camping, swimming, and public drinking fountains, can be significant as well. All of these have relevance not only from a clinical perspective, but also from a public health perspective by identifying potential means by which an epidemic from a deliberate biological attack might progress.

A critical element in the BCN history is determining whether the person has had any recent travel. On the heels of the recent SARS epidemic, the CDC advised all health care organizations and physicians’ offices to post signs asking anyone with a respiratory syndrome and recent travel to Southeast Asia, China, or Canada to take precautions upon entering a health care facility. A thorough travel history includes questions about international travel to developing nations or locales where sporadic naturally occurring Category A, B, and C infections occur. Travel to such countries or regions, especially if coupled to contact with animals, health care facilities, or sick individuals, represents a risk factor that may influence the probability of a BCN diagnosis. For example, viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) are endemic zoonoses in many central African countries. As an example of a BCN risk factor, travel to nations with strong anti-American sentiments or harboring people with such sentiments would obviously make such a possibility more likely. It is important to keep in mind that BCN terrorists run considerable risks themselves of inadvertent exposure, and it is not unreasonable to expect that the earliest warnings might ironically come as a result of disease or toxidromes in terrorists themselves or individuals who associate with them, as mentioned earlier regard to one of the September 11 hijackers. Suspicion should not be limited strictly to flagged locales of international travel. Domestic travel itself is another potential risk factor that requires consideration, especially if the travel took the individual to popular sites, such as tourist spots, national monuments, government buildings, political rallies, or major U.S. ports of entry, such as New York, Boston, San Francisco, or Los Angeles.

Clinicians need to synthesize the collected physical and historical data to determine whether there is a disease or syndrome cluster present. Identifying similar constellations of symptoms in close contacts—such as family members, co-workers, travel groups, or clustering of animal deaths in local area or traveled to areas—will be essential to raising the index of suspicion for a BCN event.

| Take a targeted history in order to assess potential for BCN event |

| Properly and safely collect samples for laboratory analysis |

| Be familiar with the BCN triage, treatment, and prophylaxis |

| Engage knowledgeably and reassuringly in patient and community education in preparedness or postevent scenarios |

| Follow up with patient, secondary contacts, and health care workers |

| Notify local and state public health and law enforcement officials |

Case of Bacillus anthracis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree