A Brief History of Biological Weapons: Introduction

Biological warfare has long been a part of the history of humanity. In fact, it is thought that the use of poisonous agents predated recorded history, though the crude use of biological weapons is first documented in written and visual form as early as 600 bc. That year, the Athenian General Solon contaminated the water supply of the besieged Greek city of Cirrha with black hellebore root. Crippled by severe diarrhea, the Cirrhaeans were defeated easily. Some two hundred years later, in about 400 bc, Scythian archers used arrowheads dipped in animal feces, blood, and decomposed carcasses to combat their opponents (Fig. 10–1). Interestingly, there is a long historical and prehistorical association between arrows and poison as dipping arrowheads in poison was the typical means for delivering poisonous substances. In both Greek and Latin, the derivation on the word toxin is related to arrow. The great Carthaginian general, Hannibal (247–182 bc), led his troops to victory over the King Eumenes of Perganum in part by hurling clay pots filled with snakes onto the decks of the Greek armada. Hannibal also used plants containing a belladonna-like chemical to incapacitate his enemies (see Chapter 21).

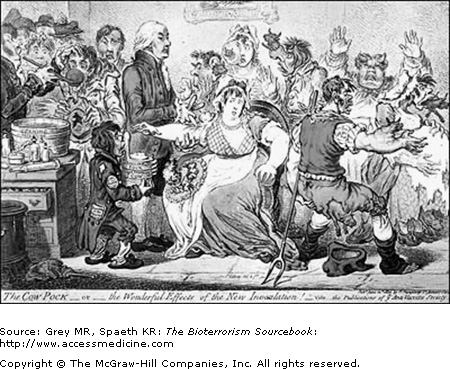

Both plague and smallpox have been used effectively to sow terror and death. During the Middle Ages, attacking armies sometimes catapulted the corpses of plague victims into besieged cities. In 1346, for example, the city of Kaffa became pestilent following a Tartar attack using this early form of biological warfare. During the French and Indian Wars in colonial America, Lord Jeffrey Amherst ordered that smallpox-contaminated blankets be sent to Native American tribes allied with the French. This type of practice became so common and so effective a military tactic that during the Revolutionary War, General Washington ordered variolation of the entire Continental army. Variolation required immunization with live vaccines taken from lesions of smallpox victims. Although effective, variolation also caused disease at a rate of about one for every 2,000 immunized individuals (Fig. 10–2).

World War I is remembered more for the utilization of chemical weapons than for that of biological ones; however, anthrax was used extensively to disrupt economic and political life by targeting enemy livestock. The brutal consequences of chemical and biological warfare during the great war galled the international community into agreeing to the first multilateral agreement to ban the use of biological and chemical weapons in 1925, the so-called Geneva Protocol.

During World War II (WWII), improved scientific understanding of microbes and microbiology spurred the creation of even more efficacious biological weapons. The Japanese military engaged in an aggressive biological weapons program from the 1930s to the end of WWII. Unit 731 (Fig. 10–3), as the notorious program was known, employed over 3,000 scientists and technicians at its peak. Japanese airplanes dropped plague-infected rice and fleas across mainland China on at least 11 different occasions as part of its effort to conquer that nation. During the war, Unit 731 conducted inhumane experiments on Chinese, Korean, Mongolian, Soviet, American, British, and Australian prisoners of war. The prisoners are known to have been experimented on with biological weapons such as anthrax, botulism, brucellosis, cholera, dysentery, gas gangrene, meningococcal infection, and plague. All told, over 1,000 prisoners were killed during these experiments, as documented during the war tribunals of the mid- and late 1940s. Japan was by no means alone in their efforts to develop bioweapons; nearly every major industrial power was attempting to develop such weapons. Fearing Germany’s use of aerial anthrax, England tested its own version on sheep herds on several islands off the coast of Scotland. Later, they stated the intended use of such a bomb was as a retaliatory measure only.

In the United States, the biological weapons development began in force after WWII. The development, done in secret, was led by George W. Merck, of Merck Pharmaceuticals and the well-known Merck Manual. War crime charges against the Japanese scientists who had developed and tested the biological agents on prisoners of war (POWs) were ultimately dropped in exchange for technical help with development of the U.S. program. The focus of the research was the weaponizing of those agents that later would come to be classified by the CDC as Category A agents. As the Cold War developed, another major focus was the development of molds and bacteria intended for Soviet wheat crops. The purpose, of course, was to destroy their agricultural base and cause food shortages and economic strife. Recognizing that the Soviets were developing similar weapons, the U.S. Army ran experiments to assess American vulnerability to bioweapons attack by simulating these attacks on major cities such as New York, Saint Louis, and San Francisco, using “harmless” pathogens. After one such test in which Serratia marcesens was dispersed in and around San Francisco, eleven people became ill and one died. The government claimed it was merely coincidence. The U.S. military also wanted to assess the feasibility of using bioweapons against the Soviets and so ran simulations in Alaska because it best simulated the climatic and landscape conditions of the Soviet Union. Similar testing was done in Okinawa to determine feasibility for use in Southeast Asia.