INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Caustics are substances that cause both functional and histologic damage on contact with body surfaces. Many household and industrial chemicals have caustic potential. Caustics are broadly classified as alkalis (pH >7) or acids (pH <7). In developed nations, increased education and product regulation (especially of acids) have decreased morbidity and mortality from caustic exposures in both adults and children. However, in underdeveloped parts of the world, exposure to caustics remains a significant problem.1,2,3,4 The challenges to exposure prevention and patient care include relative lack of childproof containers, easy and unregulated access to highly corrosive substances, cultural-specific propensities to ingest caustics in suicide attempts, sheer high volume of cases, delays to care in rural settings, malnutrition, financial resources of hospitals and families to provide the services needed, and poor follow-up.4 Alkaline ingestions predominate in the developed world,5 whereas acid ingestions are more common in developing countries.6

Caustic exposures tend to fall into three distinct groups: (1) intentional teen or adult ingestions with suicidal ideation7; (2) unintentional ingestions (the majority of which are by curious children in the toddler age group)8; and (3) other incidental, often occupational or industrial contact exposures. The majority of reported exposures are unintentional or accidental, but although less frequent, intentional ingestions account for the majority of serious injuries.1 The geographic variation in caustic ingestion circumstances, such as involved substances, intention, age of the patient, and extent of evaluation, make it difficult to create encompassing recommendations or a consensus approach.4,9,10

Many chemicals used in industry have caustic potential (Table 200-1). Household caustics are often less concentrated forms of industrial strength cleansers.

| Alkali | Found in |

|---|---|

| Sodium hydroxide | Industrial chemicals, drain openers, oven cleaners |

| Potassium hydroxide | Drain openers, batteries |

| Calcium hydroxide | Cement, hair relaxers, and perm products |

| Ammonium hydroxide | Hair relaxers and perm products, dermal peeling/exfoliation, toilet bowl cleaners, glass cleaners, fertilizers |

| Lithium hydroxide | Photographic developer, batteries |

| Sodium tripolyphosphate | Detergents |

| Sodium hypochlorite | Bleach |

| Acids | |

| Sulfuric acid | Automobile batteries, drain openers, explosives, fertilizer |

| Acetic acid | Printing and photography, disinfectants, hair perm neutralizer |

| Hydrochloric acid | Cleaning agents, metal cleaning, chemical production, swimming pool products |

| Hydrofluoric acids | Rust remover, petroleum industry, glass and microchip etching, jewelry cleaners |

| Formic acid | Model glue, leather and textile manufacturing, tissue preservation |

| Chromic acid | Metal plating, photography |

| Nitric acid | Fertilizer, engraving, electroplating |

| Phosphoric acid | Rust proofing, metal cleaners, disinfectants |

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The degree to which a caustic substance produces tissue injury is determined by a number of factors: pH, concentration, duration of contact, volume present, and titraTable acid or alkaline reserve. Acids tend to cause significant injuries at a pH <3 and alkalis at a pH >11. The physical properties of the product formulation (i.e., liquid, gel, granular, or solid) can influence the nature of the contact with the tissue. Following ingestion, solid or granular caustics often injure the oropharynx and proximal esophagus, whereas liquid alkali ingestions are characterized by more extensive esophageal and gastric injuries. TitraTable acid or alkaline reserve refers to the amount of acid or base required to neutralize the agent; the greater this value, the greater is the potential for tissue injury.

Esophageal mucosal burns from caustic ingestions are classified by a visual endoscopic grading system: grade 1 burns involve tissue edema and hyperemia; grade 2 burns include ulcerations, blisters, and whitish exudates, which are subdivided into grade 2A (noncircumferential) and 2B (deeper or circumferential) lesions; and grade 3 burns are defined by deep ulcerations and necrotic lesions. Following the initial mucosal injury, tissue remodeling occurs over roughly 2 months. In mild cases, normal esophageal function is restored, but in severe cases, dense scar tissue forms, resulting in stricture formation. Esophageal strictures are a source of significant morbidity and may require long-term treatments with dilations, stenting, or surgery. Early phases of remodeling, particularly days 2 to 14, are associated with increased tissue friability and higher risk of perforation, both spontaneous and iatrogenic.

Following caustic alkali exposures, the hydroxide ion easily penetrates tissues, causing immediate cellular destruction via protein denaturation and lipid saponification. This is followed by thrombosis of local microvasculature that leads to further tissue necrosis. Alkali injuries induce a deep tissue injury called liquefaction necrosis. Severe intentional alkali ingestion may cause deep penetration into surrounding tissues with resultant multisystem organ injuries, including esophageal injury, gastric perforation, and necrosis of abdominal and mediastinal structures. Severe injuries to the pancreas, gallbladder, small intestine, and mediastinum after intentional ingestion have been reported. Solid alkali ingestions, such as some lye preparations, have a greater potential for oropharyngeal and proximal esophageal tract injury and less for distal injury.

The most common household alkali is bleach, a 3% to 6% sodium hypochlorite solution with a pH of approximately 11. Household liquid bleach is minimally corrosive to the esophagus and rarely causes significant injury beyond grade 1 esophageal burns. Esophageal stricture was not observed as a complication of household bleach ingestion in a series involving almost 400 patients.11 However, ingestion of industrial strength bleach containing much higher concentrations of sodium hypochlorite may result in gastric and esophageal necrosis. Bleach ingestion may cause emesis secondary to gastric irritation and/or pneumonitis after aspiration. Pulmonary irritation related to chlorine gas production in the stomach or when mixed with other substances may also occur.12,13 A common reaction is the production of the highly irritating chloramine gas when bleach and ammonia household cleaners are combined.14

Injuries by strong acids produce coagulation necrosis. Dissociated hydrogen ions and their associated anions penetrate tissues, leading to cell death and eschar formation. This process is believed to limit continued hydrogen ion penetration and protect against deeper injury. When ingested acids settle in the stomach, gastric necrosis, perforation, and hemorrhage may result. Although it was previously thought that acids were esophagus-sparing with most tissue injury concentrated in the stomach, endoscopy following an acid ingestion finds a similar incidence of gastric and esophageal injury.15,16,17 Despite relatively less tissue destruction, strong acid ingestion results in high-grade gastric injuries (secondary to pylorospasm and pooling) and a higher mortality rate compared with strong alkali ingestions. Acid ingestion is sometimes complicated by systemic absorption of acid with associated metabolic acidosis, hemolysis, and renal failure.18 Hydrofluoric acid is a unique ingestion discussed in chapter 217, Chemical Burns (see Hydrofluoric Acid).

CLINICAL FEATURES

The cardinal features of caustic ingestion are a chemical burn to the oral mucosa,19 sometimes associated with chemical burns to the skin or eyes from splashes or dribbling (see chapters 217, Chemical Burns and 241, Eye Emergencies). Pharyngeal burns from ingestion produce pain, odynophagia, drooling, and vocal hoarseness. Dyspnea may be caused by edema of the upper airway, aspiration of the caustic substance into the tracheobronchial tree, or inhalation of fumes, particularly acids. Esophageal burns produce dysphagia, odynophagia, and chest pain. Ocular burns are painful, reduce visual acuity, and produce visible damage to the anterior structures of the eye.

The key priority is rapid airway assessment and stabilization. Following that, obtain a directed history to determine the type and amount of caustic ingested and the presence of coingestants. Determine if the ingestion was intentional or unintentional.

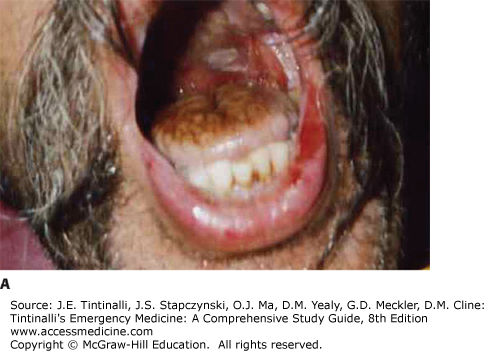

Look for signs of respiratory distress or circulatory shock. With ingestions, look for signs of pharyngeal injury (mucosal burns, drooling), respiratory injury (dysphonia, coughing, stridor, wheezing), and gastric injury (vomiting, epigastric tenderness) (Figure 200-1).5,19,20,21,22,23,24 Streaks of caustic burns on the face or chest are called “dribble burns” (Figure 200-2).

DIAGNOSIS

Conflicting data exist on the reliability of presenting signs and symptoms to predict upper GI injuries.25,26,27,28,29 Intentional ingestions are associated with higher grades of GI tract injury, with or without clinically obvious signs.30 The incidence of serious GI injury after pediatric unintentional ingestions has been the focus of many studies.5,25-27,29,31,32 Although serious esophageal injury can occur in the absence of oral burns, essentially all children with serious esophageal injuries (grade 2 or 3) after accidental caustic ingestion have some initial sign or symptom, such as stridor, drooling, or vomiting.26,27,29 Pain alone is an inconsistent predictor of severity of injury, and pain may be absent initially and early in the clinical course.

Assess for hemodynamic instability. Causes of shock include GI bleeding, complications of GI perforation, volume depletion, and toxicity from coingestants. Examine for peritoneal signs due to hollow viscous perforation. Consider mediastinitis in patients complaining of chest discomfort, and palpate the chest wall and neck for signs of subcutaneous emphysema. Inspect the eyes for ocular burns and the skin for splash and dribble burns.

LABORATORY TESTING

For children who accidentally ingest common household alkalis (e.g., bleach) or acids (e.g., toilet bowl cleaner), the need for ancillary testing is only necessary in patients with signs or symptoms of significant injury: drooling, respiratory distress, or vomiting. For an intentional ingestion, or one from a strong acid or alkali, laboratory evaluation should include a venous or arterial blood gas, electrolyte panel, hepatic profile, complete blood count, coagulation profile, lactate, and blood type and screen. Caustic ingestions can cause an anion gap acidosis based on lactate production due to direct tissue injury or shock. Strong acid ingestions may be associated with both severe anion gap (e.g., sulfuric acid) and nongap acidoses (e.g., hydrochloric acid). Obtain acetaminophen and salicylate levels to screen for potential coingestants in suicidal patients. An ECG is indicated following a hydrofluoric acid exposure to check for QT-interval prolongation from hypocalcemia.

IMAGING

Obtain a chest radiograph in patients with chest pain, dyspnea, or vomiting to check for peritoneal and mediastinal air. Thoracoabdominal CT scanning is useful to assess for esophageal injury after ingestion of strong caustics or if intra-abdominal perforated viscus is suspected. Endoscopy is the gold standard for identifying the severity of esophageal injury. IV and oral contrast-enhanced CT scanning is an alternative when endoscopy is not readily available or during the postingestion time period when the risk of esophageal perforation by endoscopy is increased (see Endoscopy section).33 Because oral contrast can interfere with subsequent endoscopic visualization, it is best to discuss the need for oral contrast administration with the endoscopist prior to the CT study. Ultrasound can be used to evaluate and follow-up corrosive gastric injury if there is perforation or severe edema preventing endoscopy.34

ENDOSCOPY

Endoscopy is the gold standard for evaluating the location and severity of injury to the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum after caustic ingestion. The controversy has been who needs endoscopy and when should it be done.28,29,32,35,36 Patients with intentional caustic ingestions should undergo early endoscopy because ingestions with suicidal intent carry the highest risk of clinically important injury. In unintentional ingestions, particularly by children, the decision to perform endoscopy is not clear cut.28,29,32,35,36 Most children with serious caustic esophageal injury will be symptomatic,32 and although there is a correlation between clinical findings and corrosive severity, lack of symptoms is judged by some authors not to be an adequate predictor of no injury.8,31,37

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree