Figure 8.1. Sacral anatomy, lateral view. A needle directed through the sacral–coccygeal membrane at a 45-degree angle will usually “pop” through the ligament and contact the anterior bone of the sacral canal. The needle needs to be rotated so that the bevel does not scrape the periosteum of this layer, and the angle of advancement changed to allow passage directly 2 to 3 cm up the canal without contacting bone again. This space is generously endowed with blood vessels, and the terminal point of the dural sac extends a variable distance into the sacral canal, but usually lies at the S2 level.

C. The major application of the caudal approach is in pediatric anesthesia, where the anatomy is more superficial and reliable, and excellent postoperative analgesia can be offered. Obstetric practice has seen a decline in the use of continuous caudals, related to the high volume of anesthetic solution required and the greater interference with the “pushing” reflex. Caudal anesthesia is available for the rare patient who cannot be offered the advantages of lumbar epidural anesthesia, such as the mother with a previous Harrington rod spinal fusion.

III. Drugs

A. The drugs used for caudal anesthesia are the same as those used for lumbar epidural anesthesia. The same considerations apply when choosing desired density (motor versus sensory) and duration of anesthesia.

B. Because of leakage through the lateral sacral foramina and the greater space in the canal, the volume of solution required is greater for caudal than for epidural anesthesia. A dose of 15 mL of solution may produce only sacral (perineal) anesthesia, whereas 25 mL is required to obtain a T10-12 level of block. This is an average of 2 to 3 mL per segment, in contrast to the requirement for half this amount with lumbar injections.

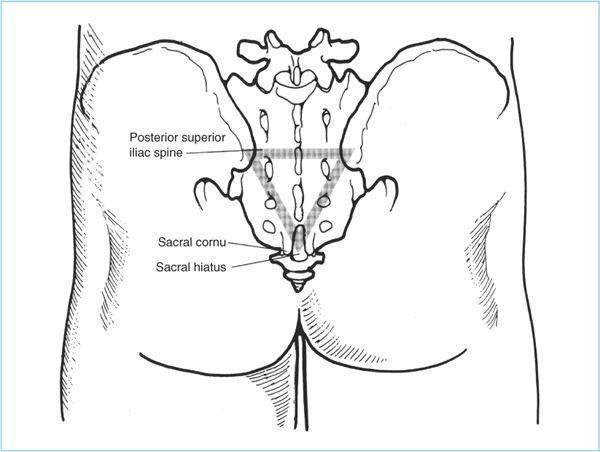

Figure 8.2. Sacral anatomy, posterior view. The sacral hiatus is covered by a thick ligament that lies between and slightly inferior to the two prominent sacral cornua. A triangle drawn between the posterior superior iliac spines and this foramen is usually equilateral in shape.

C. Age and weight are not predictable determinants of extent of anesthesia, as they are in adult lumbar epidural anesthesia. The dose requirement does appear to be slightly reduced in pregnancy; 16 to 18 mL will give a T10 level of block.

D. The same additives can be used as in epidural injection. Epinephrine prolongs duration. Clonidine and opioids will enhance degree and duration of analgesia (3,4).

IV. Technique

A. Position. Caudal anesthesia may be performed with the patient in the prone, lateral, or knee-chest position.

1. The knee-chest position is preferred in obstetrics, where the uterus makes lying prone unsuitable. For that position, the patient is instructed to turn prone but with the knees brought up into a kneeling position. It is the least “glamorous” position, but it is the most effective in causing the gluteal muscles to “fall away” from the sacral hiatus.

2. In the lateral position, the upper leg is flexed at the hip and knee, again to help spread the gluteal muscles away from the hiatus.

3. In the prone patient, a pillow is placed under the hips to flex the hip joint and spread the muscles, and the patient is also asked to spread the legs and internally rotate the feet.

B. Standard technique

1. Once the patient is in the appropriate position, the landmarks are identified. The sacral cornu may be easily palpated on the thin patient, lying just above the intergluteal crease. The sacral coccygeal membrane forms a soft valley between and just below these peaks. The position is confirmed by drawing the triangle formed by the hiatus and the posterior superior iliac spines; it should be equilateral. The membrane should also be 4 to 5 cm (1.8 to 2 in.) above the palpable tip of the coccyx. The sacral foramina may also be drawn (Figure 8.2).

2. Before skin preparation in the prone position, a small sponge is placed in the gluteal skin crease to prevent solution dripping into the perineal area. Following aseptic preparation and draping, a small skin wheal is raised with a small-gauge needle over the membrane. Generous infiltration will obscure the landmarks.

3. Deeper infiltration is done with a 22-gauge needle, again avoiding excessive distortion of the tissues. If a catheter is not used, the entire single-injection block can be performed with the 22-gauge needle, keeping in mind that the loss of resistance in the peridural space will be harder to appreciate with the smaller needle than with the traditional 17- to 19-gauge needle. Even when a large needle is used, the preliminary approach with the 22-gauge needle helps identify the membrane and canal so that the larger needle can be placed in a single attempt.

4. The needle is introduced through the anesthetized tissue to the membrane at approximately a 70-degree angle to the skin (perpendicular to the membrane [Figure 8.1]). Firm pressure will allow the needle to penetrate the fibrous band and “drop” into the caudal canal. The canal here is shallow, however, and vigorous advancement will produce a painful laceration of the periosteum of the anterior wall of the canal. If multiple attempts do not produce a penetration of the membrane within a few minutes, the landmarks are reassessed. Six percent to 10% of patients will have a fusion of the structures that prevents entry (1,2), and alternative techniques may have to be considered.

5. Once in the canal, the hub of the needle is dropped downward toward the gluteal crease so the tip now advances no more than 4 cm (1.8 in.) up the center of the canal, almost parallel to the axis of the back itself. The bevel should be rotated in the appropriate direction to reduce the chance of the sharp point lacerating the tender periosteum as it advances. The angle of the canal can normally be expected to be almost flat in relation to the skin in females, but somewhat steeper in males or blacks (the hub will drop less from the perpendicular). If the angle is 50 degrees or greater, intraosseous or transsacral placement should be suspected. The path of advancement should be directly up the caudal canal following the midline course of the spine; if lateral deviation occurs, the needle is withdrawn and the landmarks are reassessed.

6. With 2 to 4 cm (0.8–1.8 in.) of needle within the canal, a small syringe with 1.5 mL of air is attached to the hub, and gentle aspiration is performed. If no blood or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is obtained, the air is injected forcefully to gauge the resistance. There should be no resistance to injection other than the caliber of the needle itself, just as in the epidural space. Sharp pain on injection indicates subperiosteal placement and requires reinsertion.

7. If injection of this volume of air is undesirable (as in pediatric patients), other tests are available. Ultrasound guidance is becoming more common (5). Listening over the sacrum with a stethoscope for a “whoosh” sound associated with local anesthetic injection is also helpful (6). An alternative confirmation of proper entry is the use of the nerve stimulator, which will produce perirectal contractions if the needle is in the caudal canal (7).

8. If no pain or resistance is felt, an additional 5 mL of air is injected forcefully while the fingers rest lightly on the area of skin over the tip of the needle. If crepitus is felt, the needle is probably in the subcutaneous tissue and needs to be reinserted. Air may emerge laterally through the sacral foramina (Figure 8.2); this is acceptable. The patient may confirm proper needle placement by describing cramping discomfort in the posterior thighs with injection.

9. If a catheter is used, it is inserted after these confirmatory tests. A longer length of insertion (12 to 13 cm [5 in.]) into the canal may be required here than in the lumbar area, especially if lower abdominal (thoracic root) anesthesia is desired.

10. A test dose of 3 mL of local anesthetic with 1:200,000 epinephrine is injected through the catheter or needle (single-injection technique), and the heart rate or blood pressure is monitored appropriately.

11. If no intravascular or subarachnoid injection is demonstrated, the anesthetic dose may be injected and the catheter secured. Twenty minutes is usually required before adequate surgical anesthesia is obtained.

12. As with all continuous techniques, the test dose is repeated before each injection.

V. Complications

A. Intravascular injection is the most common serious problem, and is more likely here than with epidural anesthesia (8). The canal is highly vascular, but the veins have a low pressure that frustrates detection of vascular entry by aspiration of blood. Careful test doses are mandatory, along with frequent monitoring of the patient’s mental status. Incremental injection is appropriate.

B. Periosteal damage is infrequent but may be a painful disability for the patient for several weeks. Vigorous treatment with heat and anti-inflammatory drugs, along with concerned support, is needed.

C. Dural puncture is rare and carries the same risks of total spinal anesthesia and postspinal headache as epidural anesthesia.

D. Intraosseous injection is rare, but it can produce systemic toxicity similar to that of intravenous injection. Aspiration of the thick marrow is usually not possible, and absorption is slow enough that a test dose may not clearly reveal improper needle placement. Systemic symptoms may not occur for several minutes following injection of a therapeutic dose.

E. Presacral injection is also rare, but rectal injection and injection into the fetal scalp have occurred. Careful attention to landmarks and angles will reduce this possibility, and the needle need not be advanced its entire length into the tissues. Some authors suggest that obstetric caudal anesthesia is contraindicated once the fetal head has descended into the pelvis (and lies just anterior to the sacrum).

F. Hypertension has also been described on rapid injection. This may be due to a response to compression of the cord or spinal nerves. It is usually transient and can be avoided with slow injection.

REFERENCES

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree