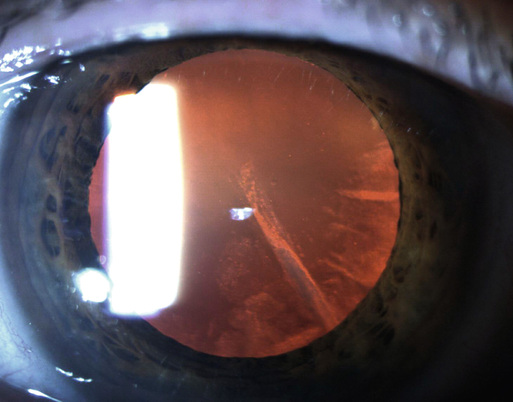

Jack Stringham, James T. Banta Ancient physicians thought that a crystalloid structure (lens) rested in the center of the eye and was responsible for vision. People lost vision when an abnormal humor developed and flowed in front of the lens. They called this a cataract (Latin for waterfall).1 Today, the term cataract refers to the opacification of the crystalline lens of the eye. The most recent World Health Organization estimate lists cataract as the leading cause of blindness worldwide, accounting for 48% of world blindness or affecting 18 million people. Cataract causes some degree of visual impairment in nearly 20.5 million Americans or one in six Americans aged 40 years and older.2 The most common form of cataract is associated with increasing age and progressive oxidative damage to the crystalline lens. Every person who lives long enough will develop some degree of cataract. As life expectancy increases and the population ages, visual loss from cataract will have an even greater medical and economic impact. In the United States, prevalence estimates of visually significant cataract increase with age for both men and women, from 4% and 10% for men and women aged 55 to 64 years to 39% and 46% for those older than 75 years.2 The anatomic function of the crystalline lens is to focus incident light on the retina. Opacification of this lens, a cataract, prevents light from focusing on the retina, causing loss of vision. The natural aging process of the crystalline lens involves an increase in mass, thickness, and the development of a yellow hue with an associated loss of accommodative capacity. Initially these changes cause minimal visual impairment, but with time the lens becomes more opaque, leading to a significant decrease in vision and forming an age-related cataract. Cataracts develop in everyone who lives long enough, but their formation is hastened by trauma, exposure to certain medications (e.g. corticosteroids), metabolic disorders such as diabetes, and oxidative stress from smoking or ultraviolet light. Congenital cataracts can also form; these can be idiopathic in nature or can be caused by an underlying infection or metabolic disease.2 The classic presentation of age-related cataract is with nonpainful, progressive loss of visual acuity. Patients often describe blurred or hazy vision and haloes or significant glare with bright lights; a common complaint is difficulty driving at night. Another common presentation is frequent changes in a patient’s eyeglass prescription. The majority of refractive changes (typically an increase in myopia) in older adults are the result of cataract progression. Nuclear sclerotic cataracts tend to affect distance vision more than reading vision, whereas cortical cataracts result in more symptoms of glare in dim illumination. Posterior subcapsular cataracts tend to progress more rapidly and occur in younger patients than do nuclear sclerotic and cortical cataracts. Posterior subcapsular cataracts can cause glare symptoms and difficulty reading in bright illumination.2 Cataracts may progress during the course of months to years. Patients may occasionally report a sudden decrease in vision. In these patients the cataract has progressed slowly but just recently reached the point at which it noticeably inhibited the patient’s ability to perform some activity. Nontraumatic cataracts are usually bilateral but may be asymmetric.2 Cataracts are often an isolated finding, but a full ophthalmic examination is indicated to determine if other causes of visual loss may be present. A cataract will not cause injection of the conjunctiva, corneal opacification, or pain—except in rare instances of traumatic or hypermature cataracts. The pupils should constrict normally to light. Direct ophthalmoscopy may reveal hazy visualization of the optic nerve and retina as a result of the lens opacity. Cataractous lens changes are best appreciated with use of a direct ophthalmoscope with a dilated pupil, focusing on the red reflex. Nuclear sclerotic changes may cause the reflex to appear dull or asymmetric. Cortical lens changes may cause focal, segmental, or spokelike dark areas in the reflex (Fig. 71-1); posterior subcapsular changes typically appear as a central, dark plaque (Fig. 71-2).

Cataracts

Definition and Epidemiology

Pathophysiology

Clinical Presentation

Physical Examination

Cataracts

Chapter 71