Chapter 11 Care of the Patient with Pain

Pain is a complex experience for patients. The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain in the following manner: “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.”1 McCaffery and Beebe2 define pain as “whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever he or she says it does.” While pain is an event that most humans experience, it is always subjective and each of us experiences pain differently.

Oligoanalgesia, the undertreatment of pain, is the greatest risk to accomplishing pain relief for the patient.3,4 One of the primary responsibilities to patients in the emergency department (ED) is to assess pain effectively and manage pain to the best of our ability.

Types of Pain

There are two categories of pain, acute and chronic, which can be further divided into three types: somatic, visceral, and neuropathic (Table 11-1). Noting the type of pain will help in determining the cause and will support choosing an appropriate intervention. More than one kind of pain or mechanism for pain can be present in an individual patient.

| TYPE OF PAIN | SITES | CHARACTERISTICS |

|---|---|---|

| Somatic | Skin and subcutaneous tissues | Localized |

| Bone, muscle, blood vessels, and connective tissues | Constant and achy | |

| Visceral | Organs and the linings of the body cavities | Poorly localized Diffuse, cramping |

| Neuropathic | Central and peripheral nervous systems | Poorly localized Shooting, burning, sharp, numbness, tingling |

Pain Assessment

The challenge of assessing a subjective complaint in an objective manner continues to affect the approaches that emergency nurses choose in caring for the patient with pain. Conducting a comprehensive assessment of pain in a nonjudgmental manner creates a trusting relationship and improves communication between the nurse and the patient. Consistent use of pain assessment tools that have been determined to be simple, reliable, valid, population specific, and sensitive to changes in pain intensity is essential to effectively evaluate the patients presenting for care.5

Assessment of a patient’s pain begins at the time of arrival in the ED and continues throughout the patient’s ED stay, with the frequency of reassessment determined by the patient’s condition and the interventions provided for pain relief. Each patient should be assessed for the presence and intensity of pain, regardless of the chief complaint and focused on the reason for presenting to the ED for care. The mnemonic PQRST provides the parameters to be assessed (Table 11-2).

| P | Palliative or precipitating factors |

| Q | Quality of pain |

| R | Region and radiation of the pain |

| S | Subjective description of pain (use pain rating scale) |

| T | Temporal nature of the pain |

Pain Assessment Tools

All EDs should establish a standard for pain assessment and response to treatment based the hierarchy of assessment techniques (Table 11-3). No one tool is useful in all populations. Determining which pain assessment tools will be used in the ED supports achieving the goal of evidence-based, consistent pain assessment of the diverse population of patients seen in the ED.

TABLE 11-3 HIERARCHY OF PAIN ASSESSMENT TECHNIQUES

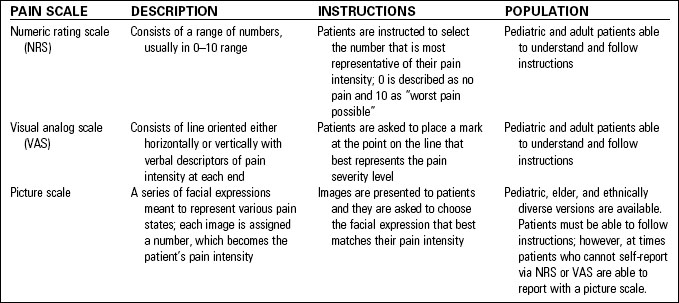

The most reliable of these severity assessment tools are based on patients’ self-reporting.6 The numeric rating scale, the visual analog scale, and picture scales are self-report pain assessment tools (Table 11-4). Some patients have trouble using a horizontal, classic left-to-right pain scale, especially if their primary language is read vertically or from right to left. Turn the scale vertically instead. Place the “10” at the top because sequences that progress upward are more universally recognizable than those that progress downward.7,8

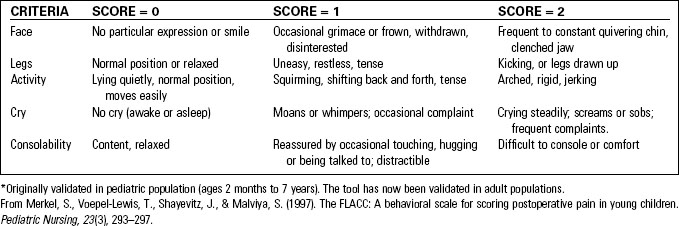

Younger children may not understand the concept of ranking. Determine the child’s ability to use a numerical scale by asking, “Which number is larger, nine or five?” For those who cannot accurately answer that question, use the Finger Span Scale. The child is asked to move the forefinger and thumb apart to report the magnitude. Demonstrate it to the child by using the word for pain, such as “hurt,” that is most familiar to the child. Having the thumb and forefinger together represents “no pain,” a small distance between fingers represents “tiny” pain, and so on until far apart represents “most possible pain.” Estimate based on the finger spread.9 Using the finger span assessment with FLACC (see Table 11-5) will improve overall assessment.10

When patients cannot self-report, using a behavioral tool that results in a numeric rating keeps the documentation of the pain assessment consistent with self-report tools.11–14

• PIPP (Premature Infant Pain Profile), for premature and term neonates, uses gestational age, heart rate, oxygen saturation, behavioral state, brow bulge, eye squeeze, and nasolabial furrow.15–17

• FLACC (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, and Consolability) assesses the five categories indicated in the name and assigns a score of 0 to 2 for each category. See Table 11-5.

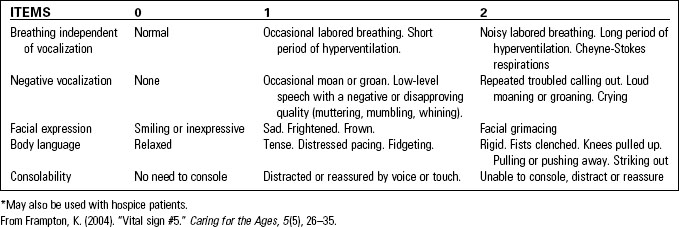

• PAINAD (Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia) Scale uses breathing independent of vocalization, negative vocalization, facial expressions, body language, and consolability. See Table 11-6.

Regardless of the pain assessment tools used in the ED, documentation of the patient’s pain should be done in a consistent format and include identification of which pain assessment tool is being used.18

Providing Comfort for the Patient in Pain

The emergency nurse who advocates for the patient’s comfort throughout the ED visit supports the ability of the emergency physician to meet the patient’s expectation of pain relief. While appropriate management is based on the etiology of the pain, it is important that we begin the treatment of pain while simultaneously exploring the cause of pain. Studies found no difference in physical findings or diagnostic accuracy between patients who received morphine and those who received a placebo.19–21 The American Pain Society, American College of Emergency Physicians, and Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians recommend that analgesia not be withheld during a diagnostic workup.22–24

The choice of pain management strategies depends on the etiology and whether the pain condition is solely acute, acute with chronic pain, or a breakthrough chronic pain condition. In most circumstances, using an approach that is multimodal and tailored to the individual is the pathway to success.25

Pharmacologic Interventions

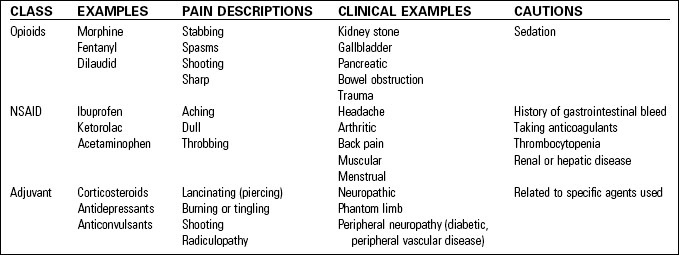

Pharmacologic pain management strategies fall into four classes—local, nonopioid, opioid, or adjuvant—and include choosing the right medication (Table 11-7) and route for the patient’s problem. Using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in conjunction with opiates can decrease the dose and frequency of opiates needed.25 Caution must be taken when using combination products (opiates with acetaminophen or NSAID) because of the risk of exceeding the maximum daily dose of the nonopiate.26 Whenever possible, administering these medications in their single-ingredient format makes it easier to adjust dosage of the opiate and keep track of the amount of nonopiate being administered.

Studies have found that 1000 mg of acetaminophen (Tylenol) and 800 mg of ibuprofen (Motrin) at the same time is effective for mild to moderate pain, especially for musculoskeletal conditions, dental pain, or postoperative pain. The combination of different actions, one central and one peripheral, provides additive pain-relieving activity and is more effective than either drug used alone.27–30

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree