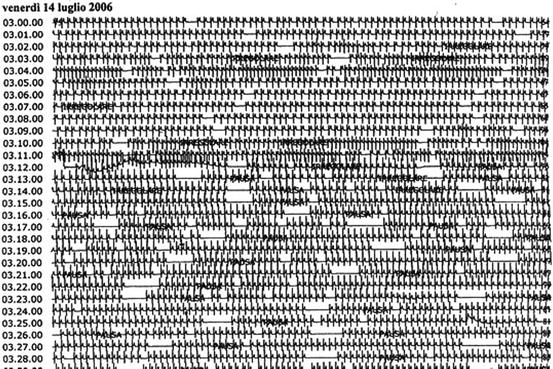

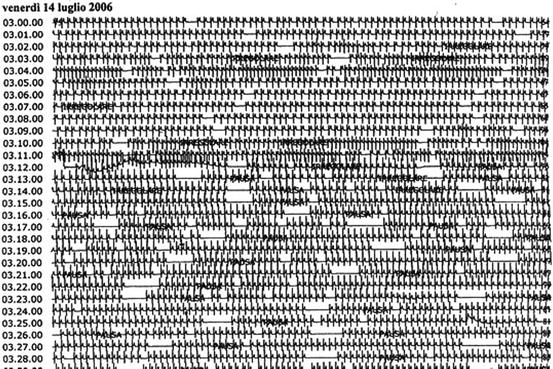

Fig. 10.1

Amateur football player, 17 years old, suspected cocaine intoxication and “chaotic atrial arrhythmia,” i.e., sinus rhythm and polymorphic supraventricular ectopic beats

Cocaine can also induce ECG modifications such as a V1–V3 ST elevation (coved type) typical for Brugada syndrome, due to a selective block of myocardial sodium channels in subjects with latent arrhythmic disease [33].

Moreover, patients abusing cocaine also commonly mix it with different substances such as hallucinogens, strychnine (“dead hit”), heroin (“speedball”), and alcohol (“liquid lady”): in case of associated intake of alcohol and cocaine the risk of sudden death has been found to be higher probably because of the additive effects of a metabolite, coca-ethylene, which can block the dopamine reuptake, enhancing the toxic effect of the cocaine used alone [34].

10.3.1.3 Cannabinoids

Many patients can present to the ED after consumption of cannabinoids, including marijuana and hashish, with different arrhythmic disorders: exercise-related sinus tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, supraventricular and/or ventricular ectopic beats, and severe ventricular arrhythmias [35, 36], which can be mediated by catecholamines (Fig. 10.2).

Fig. 10.2

ECG-Holter monitoring of a young male athlete (soccer player), 22 years old. Chronic use of cannabinoids and sporadic use of cocaine. This ECG-Holter tracing taken overnight shows a sick sinus syndrome with sinus arrest, sinus tachycardia, and nonsustained atrial tachycardia

The onset of arrhythmias is usually 30 or 60 min after smoking, and the arrhythmic disorders are related to the dose. At low and moderate doses there is an increase in sympathetic activity and a decrease in parasympathetic activity, and patients commonly present with sinus tachycardia, ectopic beats, or paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. At higher doses, there is a decrease in sympathetic activity and an increase in parasympathetic activity that can favour atrial fibrillation [37].

10.3.2 Prescription Drugs

Different common prescription drugs can induce arrhythmic complications in cases of involuntary abuse, suicidality, or in case of multiple interactions. Rather than providing an exhaustive list of all possible arrhythmias related to the use or abuse of prescription drugs, this section aims to help physicians working in the ED to get used to a comprehensive attitude on managing not only the arrhythmias but also the whole pathologic affections.

Here, the most common prescription drugs whose abuse or misuse can present with arrhythmias are reviewed.

10.3.2.1 β-Blockers

Abuse of β-blockers can induce bradyarrhythmias with atrio-ventricular blocks of various degrees, sinus bradycardia, junctional and ventricular escape rhythms, bradycardia-dependent ventricular ectopic beats, and asystole, especially in patients with underlying structural and electrical disorders.

Among the β-blockers, sotalol is associated with a high rate of cardiac dysrhythmias [1] and related QT prolongation. Other symptoms can be associated as hypotension, syncope, muscular contractions, mydriasis, bronchial obstruction and often hypoglycaemia especially in children.

The doctors in the ER should perform a gastrointestinal decontamination with activated charcoal and a correction of the hypoglicemia and other electrolyte disorders if present. Intravenous dopamine or adrenaline may be necessary, and the cardiologist should prepare a central venous access for a promt temporary pacing if required.

10.3.2.2 Digitalis

Patients presenting in the ED with symptoms of digitalis intoxication, mainly gastrointestinal in nature, such as anorexia, nausea, and vomiting, may suffer from many different dysrhythmias involving almost any rhythm or conduction disturbance [38–40]. The most common disorders are first-degree AV block or more advanced AV block degree and premature ventricular contractions.

Digoxin has two main actions in the cardiac myocyte: inhibition of the Na+-K+ Adenosinetryphosphate pump, interfering with AV conduction and increase in calcium concentrations, enhancing automaticity [41].

It is therefore important to recognize associated electrolyte disturbances, acid-base alterations, and renal or hepatic failure. In digoxin intoxication, hyperkalemia can be also sustained via a toxic mechanism of the Na+-K+ pump, which can be difficult to treat and can result after the treatment in hypokalemia.

In the presence of bradyarrhythmias, both atropine and cardiac pacing are usually effective. The most effective treatment for digitalis overdose is the administration of antidigitalis immunoglobulin IgG.

The administration of magnesium and lidocaine often successfully treats premature ventricular contractions.

10.3.2.3 Antiarrhythmic Drugs

A patient with a history of atrial fibrillation treated with an antiarrhythmic drug such as flecainide or propafenone can present at the ED with an atrial flutter with a 2:1 or 1:1 atrioventricular conduction, or, in cases of drug abuse, also with a wide complex tachycardia related to class I effects on Na channels and QRS prolongation (Fig. 10.3).

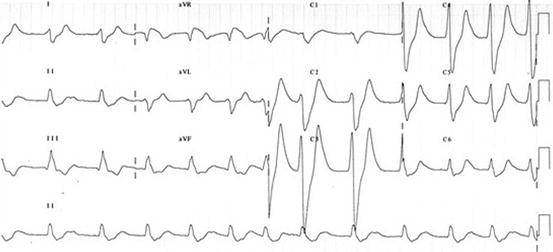

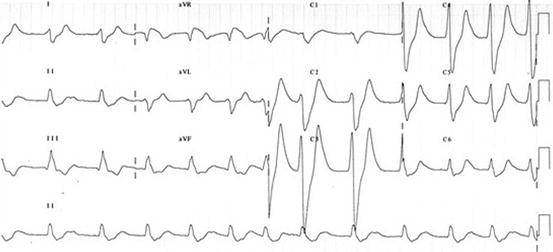

Fig. 10.3

A 60-year-old woman, 60 kg, with a history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation; intake of 300 mg flecainide per os

10.3.2.4 Benzodiazepine

When a patient with a history of anxiety presents at the ED with palpitations, the medical history plays, as usual, an important role; in fact, discontinuation of benzodiazepine (BDZ) can cause a withdrawal syndrome with reactions that vary in severity and duration. Withdrawal syndrome is more common with triazolam and BDZs with a short to intermediate half-life, in particular if taken in repeated doses during the day, whereas the syndrome is rare with long-half-life BDZs and virtually absent with BDZ analogues such as zolpidem and zopiclone.

Arrhythmias during withdrawal syndrome are induced by autonomic arousal caused by sympathetic hyperactivity, and include mainly sinus tachycardia and ectopic beats, often associated with blood pressure imbalance (orthostatic hypotension and mild systolic hypertension). The administration of β-blockers or clonidine can help in managing reactions resulting from sympathetic hyperactivity [42].

10.3.2.5 Antidepressant Agents

Depressed patients seem to be predisposed to cardiac arrhythmias, one of the proposed mechanisms involves a reduced parasympathetic nervous system activity, that can be often present as a decreased heart rate variability [43].

In patients with depression presenting with dysrhythmias in the ED, it is important to recognize the different classes of drugs.

Tricyclic antidepressant agents (TCA), such as imipramine, amitriptyline, and clomipramine, act as nonselective monoamine reuptake inhibitors. TCAs induce quinidine-like effects that are frequently encountered in older patients and children. On surface ECG it’s often recognizable an intraventricular block and atrio-ventricular conduction block of different degrees with an increase in QRS width and PR interval; moreover, there are repolarization abnormalities with QT interval prolongation and negative T waves: therefore these patients present with a higher risk of ventricular arrhythmias, in particular torsade de pointes. TCA can also induce sinus tachycardia (5–20 % of patients treated), with a mean increase of 15–20 bpm, probably caused by peripheral anticholinergic activity. Patients with cardiac diseases treated with class IC antiarrhythmic drugs (flecainide, propafenone) or quinidine should be closely monitored because the interaction between these drugs can lead to an increase in TCA blood concentration.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) include fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, and citalopram, among others. A sinus tachycardia can be frequently recorded and, rarely, palpitations. In older patients SSRI can lead to sinus bradycardia and, rarely, syncope. In the case of drug overdose rhythm disorders, both bradyarrhythmia and tachyarrhythmia, as well as hypotension, are frequently present [44]. SSRI inhibits hepatic CYP3A4 and it is important to avoid or administer with reduced doses antiarrhythmic drugs as amiodarone, flecainide, propafenone, and lidocaine (i.v.) or sildenafil. [44, 45].

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI), such as phenelzine, tranylcypromine, and isocarboxazid, comprise the third main group of drugs used in clinical practice. A patient taking MAOI and presenting at the ED with palpitations and either tachycardia or bradycardia should be evaluated for a hypertensive surge, which has sometimes been reported as fatal. The anamnesis plays a pivotal role; in fact if the patient has ingested cheese or other foods with a high tyramine content, the arrhythmias could be due to norepinephrine release and an exaggerated adrenergic reaction induced by high tyramine blood levels [46–48].

10.3.2.6 Antibiotics

Patients treated with antibiotics can often present at the ED with sinus tachycardia or palpitations related to ectopic beats or to high rate atrial fibrillation; both dysrhythmias are probably related to the underlying condition (usually an infection) and subsequent fever and electrolyte disturbances.

In any event, a 12-lead ECG is mandatory to exclude a QTc prolongation and the risk of ventricular arrhythmias, in particular torsade de pointes.

These arrhythmias can be due to the following classes of antibiotics:

Macrolides such as erythromycin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin. The risk of QT prolongation is higher if an H1 antagonist (e.g., terfenadine, astemizole) is administered at the same time. QT prolongation has been described with erythromycin, spiramycin and, less frequently, clarithromycin and azithromycin. Moreover, palpitations have been reported in patients taking azithromycin. An increase in digoxin levels has been reported in patients receiving erythromycin attributable to killing of digoxin-metabolizing bacteria [49].

Fluoroquinolones such as levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin. Rarely, ventricular arrhythmias resulting from QT prolongation have been described during fluoroquinolone therapy.

10.4 A Suggested Algorithm/Pathway for Diagnosis and Treatment

All patients with bradyarrhythmia or tachyarrhythmia and suspected drug abuse or intoxication | What to do | How to do it |

|---|---|---|

Medical history and identification of suspected drug/s

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|