Chapter 20

Cancer pain

At the end of this chapter readers will:

1 Understand the magnitude of the problem of cancer pain.

2 Understand the circumstances in the cancer journey when pain may occur.

3 Be able to describe the types of pain.

4 Understand that the experience of pain can have physical, psychological and spiritual dimensions.

5 Understand the principles of pain management.

6 Understand the barriers to good pain management.

7 Appreciate the personal issues confronted by therapists dealing with cancer pain.

OVERVIEW

Cancer pain management will be discussed in some detail, with an overview of medication management and consideration of non-medication management of pain. However, this is not a text on how to manage pain. A useful resource is the clinical guideline entitled Adult Cancer pain (v1.2010) published by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) (National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2010). Box 20.1 defines some key terms.

FREQUENCY OF PAIN IN CANCER

Pain in cancer is common, with reported prevalence ranging from as low as 14% up to 100% (National Institutes of Health 2002). Most studies report a range, such as 54–92% (Teunissen et al 2007), with such differences in prevalence largely due to differences in definition, the point along the cancer journey that is being examined and the setting where the measures take place. For example, the prevalence of pain in palliative care and pain centres is higher than in oncology settings.

It is important to note that pain is not universal in people with cancer, and that some people have no pain at all. In one study concentrating on the palliative phase of cancer, 30% of people experienced no pain, 37% had minimal to mild pain, 28% described moderate to strong pain and 5% had severe to extreme pain (Wilson et al 2009).

Cancer pain is very costly, both in direct and indirect terms. Lema et al (2010) estimate that neuropathic pain costs the USA $2.4b per annum.

Types of cancer pain

Symptoms can be defined as ‘subjective experience[s] reflecting changes in the biopsychosocial functioning, sensations, or cognition of an individual’ (Dodd et al 2001). The sensation of pain arises from stimulation of pain receptors or damage to the neural tracts that carry pain. However, the experience of pain is modified by a range of factors.

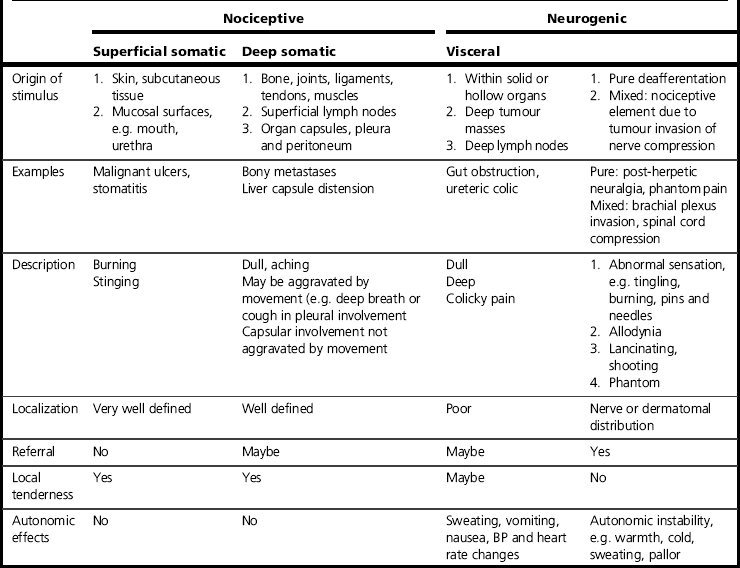

There are three types of pain which may arise for patients with cancer: pain that is secondary to tumour growth and invasion of structures, pain that results from treatment of the cancer and pain not associated with the tumour or the treatment. Classification of pain by physiological type has been described for some time (Portenoy & Hagen 1990), but Ashby demonstrated that classifying pain by its mechanistic basis influences the type of pain treatment that is offered (Ashby et al 1992). Two major categories of pain are recognized: nociceptive pain and non-nociceptive pain. Nociceptive pain arises from the stimulation of nociceptive pain receptors (see Table 20.1 for definition), and the nature of the pain varies depending on the structures where those pain receptors are located. Non-nociceptive pain is either neurogenic (arising from damage to or irritation of the neural tracts) or non-neurogenic. The physiology of pain is discussed in Chapter 6.

Table 20.1

Mechanistic classification of cancer pain (from Ashby et al 1992)

Ashby MA, Fleming BG, Brooksbank M, Rounsefell B, Runciman WB, Jackson K, et al Description of a mechanistic approach to pain management in advanced cancer. Preliminary report. PAIN, 2007. 51(2): 153–161.

Cancer pain may be long-standing, of more than 3 months’ duration, and so has many chronic pain features. It also changes according to tumour-growth damage to tissues and to the impact of some treatments, and so has acute pain features (Foley 1987).

Foley (1987) describes five different cancer pain types.

1. Patients with acute pain associated with the cancer or the treatment. Acute pain associated with the cancer heralds the onset or recurrence of the illness, bringing with it associated psychological ramification. In contrast, acute pain associated with treatment is self-limiting and pain tolerance is often high, with the patient is hopeful about outcome, and consequently psychological effects may be limited. In both cases, treatment needs to be targeted at the cause of pain.

2. Patients with chronic pain, either from the cancer or the therapy. Chronic pain associated with the cancer reflects tumour progression and psychological issues become much more important for these patients. Anxiety and feelings of hopelessness can further exacerbate the pain. Chronic pain may also be due to soft tissue, nerve or bony injury related to cancer treatment, and be unrelated to the tumour. Identifying this group is import in order to reassure the patient that the pain is not caused by their cancer. Treatment of patients with chronic pain is aimed at the symptom rather than the cause.

3. Patients with chronic pain from another source, generally pre-existing. These patients often already have psychological and functional limitations, and require considerable support as the presence of multiple illnesses is very taxing.

4. Patients with pain who are also actively involved with illicit drug use. These patients are very difficult to treat.

5. Patients who are dying and have cancer pain. The focus of treatment is on maximizing comfort and providing psychological care. The family must also be considered in caring for this group.

IMPACT OF AND RESPONSES TO CANCER PAIN

Anxiety, depression, anger and a sense of helplessness are common responses to unrelieved cancer pain. In turn depression and anxiety related to a cancer pain and its treatment can aggravate pain. People with advanced cancer and severe pain are twice as likely to experience clinical depression and three times more likely to have an anxiety disorder as those with less severe pain (Wilson et al 2009). Pain may also impact on a person’s cognitive function, particularly placing greater demands on memory. Not surprisingly, the effect of ongoing pain is to reduce the individual’s feeling of control. It is important for the therapist to acknowledge this heightened sense of loss of control and to modify their approach accordingly. The functional impact of cancer pain also limits peoples’ ability to participate in meaningful activities and relationships, with pain from cancer interfering more with enjoyment of life than pain from other causes (Daut & Cleeland 1982; Ferrell et al 1995).

An individual’s experience and expression of pain is partly socioculturally determined. Their previous experience of pain within their family, and their culture’s perception of pain, suffering and illness influence the person’s thoughts and coping styles with regard to pain. In contemporary management regimes for cancer, many patients are cared for predominantly at home and their pain management occurs at home. Therefore the patient and/or their family carers are often responsible for medication and other pain-reduction procedures. It has been found that patients are often under-medicated due to beliefs held by themselves and/or their caregivers that they should put up with pain as long as possible, and due to fear of addiction (Ferrell et al 1995; Hussein Al-Atiyyat 2008; Yeager et al 1997). Responses to cancer pain therefore clearly relate in some part to the attitudes, beliefs and knowledge of patients and carers.

Cancer pain in the later phase of the disease is a marker for patients that their disease is progressing. This opens up questions about one’s mortality and related spiritual issues. Otis-Green et al (2002) note that spiritual distress may occur when there is conflict between the patient’s experience of pain and suffering and their world view, leading to anxiety, depression, anger and withdrawal, as well as physical pain.

ASSESSMENT AND MEASUREMENT OF CANCER PAIN

Readers are advised to refer back to Chapter 7, which covered assessment and measurement issues in more depth. Inadequate cancer pain assessment results in poor control of pain. The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, Adult Cancer Pain (National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2010) recommend that pain assessment should involve assessment of factors such as:

• characteristics/quality of the pain

• pain history (sites, severity, duration, mood, previous pain experience, etc.)

• factors that exacerbate or relieve pain

• psychosocial factors (patient distress, psychiatric history, social supports, etc.)

• cultural, spiritual and religious considerations

Assessment considerations

Assessment of cancer pain should be multidimensional and multidisciplinary. Pain involves a complexity of sensory, cognitive, behavioural and affective phenomena, requiring a coordinated assessment effort by different disciplines. The source of the pain can be identified by assessing the location, distribution, quality, intensity and duration (Table 20.1). Comprehensive assessment of pain should also consider other symptoms that may interact with, and exacerbate, pain, such as fatigue. Lawlor (2003) emphasizes that awareness of suffering and other psychosocial and spiritual distress in association with cancer pain is essential to palliative care. Hence a multidimensional approach to assessment that encompasses evaluation of the patient’s physical, social and psychological function and spiritual needs is vital (Otis-Green et al 2002).

Anderson & Cleeland (2003) suggested that patients with cancer pain may have ‘reporting biases’ because cancer is an anxiety-provoking condition. They may fear that a change in pain means more than in other conditions, so there is a need to assess in a way to minimize bias, either towards under-reporting or over-reporting. Clients may under-report their pain, due to a concern about not being a nuisance to ward staff or family members, or due to denial of the increasing seriousness of their condition. A new pain in a patient with cancer should always be investigated thoroughly. It may signal a treatable new problem or the exacerbation of an existing problem that requires reassessment. A change in the patient’s report of pain should be reported immediately to the treating physician and other members of the team.

One of the key recommendations for the assessment of cancer pain is that it is reassessed at frequent intervals (National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2010). Cancer pain needs to be assessed frequently to fully understand changes in the pain and underlying influences, such as proximity to or distance from time of last medication, physical activity, anxiety or time of day. In addition the time of day that pain is assessed is important because cancer pain may be worse in the early evening and better in the early morning (Klein 1983).

The fluctuations in pain relative to various reference points, such as the time of day, medication status, activity level or anticipation of some event, need to be charted. Patients with uncontrolled pain need frequent assessment. In this situation pain should probably be assessed at least daily, and sometimes more often is necessary, particularly to determine response to treatments (National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2010).

The implications of this type of assessment regime are that the measurement tools need to be accurate, brief and comprehensive to avoid over-taxing the client. They also need to be appropriate for multiple evaluations and still be reliable, and must be practical for use with severely ill people (Ahles et al 1984).

The guidelines produced by the NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2010) state that since pain is subjective, the patient’s self-report should be a standard source of assessment. In order for this to be an effective policy to follow, the treatment ethic of the centre must encourage accuracy in patient self-report by acting on information provided by the patient and by providing sufficient education about the aspects of illness and its treatment so that the patient is unafraid to give information about their pain. Simply asking a question such as, ‘How is your pain?’ does not provide enough opportunity to fully describe it. Various tools which have been shown to be sensitive and reliable should be used (see Chapter 7).

Methods for assessing pain include the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), which were described in Chapter 7. The VAS rates pain intensity and is short and easy to use. Its reliability has been established with patients with cancer. The MPQ is longer, but is multidimensional and also has good psychometric properties. If the patient is especially ill or fatigued, the short-form MPQ can be used.

The NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2010) also suggest that patients be asked to describe the characteristics or quality of pain. The particular descriptive words used can give valuable clues about the cause of the pain. For example, pain described as burning or tingling is likely to involve neural structures.

Assessment of symptoms that may interact with pain may be achieved through symptom-specific measures or through measures that assess multiple prevalent cancer-related symptoms, such as the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (Portenoy et al 1994).

There are many approaches to the measurement of function and wider patient concerns. Disease-specific quality-of-life instruments are one way of ascertaining the interface between cancer pain, other symptoms and functioning. Several measures of quality of life (QOL) for the patient with cancer have been developed which have acceptable psychometric properties. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale (FACT Scale) is a brief, 33-item, self-report measure of QOL over the past week. It covers physical well-being, social/family well-being, relationship with doctor, emotional well-being and functional well-being (Cella et al 1993).

Another measure is the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 (version 2.0) (Aaronson et al 1993; Osoba et al 1997). It consists of 30 items which tap the nine subscales of function (physical, role, cognitive, emotional and social) and associated cancer-related symptoms such as fatigue, pain, nausea and vomiting, and global health, and QOL.

Impact of pain on the occupations of daily life

Pain from cancer can have an impact on an individual’s occupations of daily life. Associated fatigue can also impair occupational performance. Patterns of activity, ability to perform functional activities of daily living, ability to meet desired occupational goals, QOL and coping strategies should also be assessed. The impact which the pain and the cancer has had on the person’s ability to perform their daily life occupations should be a particular emphasis of the occupational therapist. Again, methods for assessing these features were reviewed in Chapter 7.