Shoulder Dislocation and Reduction

Olabiyi Akala and Maureen Gang

INDICATIONS

![]() History and clinical examination consistent with shoulder dislocation

History and clinical examination consistent with shoulder dislocation

![]() Anterior Dislocation (~95%)

Anterior Dislocation (~95%)

![]() Mechanism

Mechanism

![]() Force applied to an externally rotated, abducted, and extended arm

Force applied to an externally rotated, abducted, and extended arm

![]() Rarely secondary to a blow to the posterior shoulder

Rarely secondary to a blow to the posterior shoulder

![]() Examination

Examination

![]() Prominent humeral head anteriorly and a shallow depression inferior to the acromion may be observed

Prominent humeral head anteriorly and a shallow depression inferior to the acromion may be observed

![]() Affected extremity usually held in abduction and external rotation

Affected extremity usually held in abduction and external rotation

![]() Posterior Dislocation (2%–4%)

Posterior Dislocation (2%–4%)

![]() Mechanism

Mechanism

![]() Axial loading of adducted and internally rotated arm

Axial loading of adducted and internally rotated arm

![]() Less commonly due to direct blow to anterior shoulder or fall on an outstretched arm

Less commonly due to direct blow to anterior shoulder or fall on an outstretched arm

![]() May result from violent muscle contractions: e.g., seizures, electric shock, psychiatry patients

May result from violent muscle contractions: e.g., seizures, electric shock, psychiatry patients

![]() Examination

Examination

![]() Prominence of posterior shoulder with flattening anteriorly; may be subtle

Prominence of posterior shoulder with flattening anteriorly; may be subtle

![]() Affected extremity typically held in adduction and internal rotation

Affected extremity typically held in adduction and internal rotation

![]() Patient usually unable to externally rotate affected extremity

Patient usually unable to externally rotate affected extremity

![]() Inferior dislocation (luxatio erecta)—rare

Inferior dislocation (luxatio erecta)—rare

![]() Mechanism

Mechanism

![]() Forceful hyperabduction of the affected extremity

Forceful hyperabduction of the affected extremity

![]() Examination

Examination

![]() Affected arm is held above the head

Affected arm is held above the head

![]() Patient is unable to adduct the affected extremity

Patient is unable to adduct the affected extremity

![]() Radiographs demonstrate glenohumeral dislocation

Radiographs demonstrate glenohumeral dislocation

CONTRAINDICATIONS

![]() Any associated fracture—particularly fracture of the humeral neck

Any associated fracture—particularly fracture of the humeral neck

![]() Obtain orthopedic consultation

Obtain orthopedic consultation

![]() Any associated neurologic deficit

Any associated neurologic deficit

![]() Closed reduction may still be attempted but multiple attempts should be avoided

Closed reduction may still be attempted but multiple attempts should be avoided

RISKS/CONSENT ISSUES

![]() Recurrent dislocation

Recurrent dislocation

![]() Risk dependent on age at initial dislocation, with recurrence risk up to 90% for those <20, up to 70% for those between 20 and 40 and between 2% and 4% for those older than 40

Risk dependent on age at initial dislocation, with recurrence risk up to 90% for those <20, up to 70% for those between 20 and 40 and between 2% and 4% for those older than 40

![]() Increased risk of associated rotator cuff injuries in patients >40 years of age

Increased risk of associated rotator cuff injuries in patients >40 years of age

![]() Complications of reduction

Complications of reduction

![]() Risks associated with procedural sedation

Risks associated with procedural sedation

![]() Neurovascular injury

Neurovascular injury

![]() Fracture of humerus and glenoid

Fracture of humerus and glenoid

![]() General Basic Steps

General Basic Steps

![]() Thorough examination of affected extremity, including neurovascular status

Thorough examination of affected extremity, including neurovascular status

![]() Analgesia/sedation/muscle relaxation

Analgesia/sedation/muscle relaxation

![]() Reduction via preferred technique

Reduction via preferred technique

![]() Postreduction care and follow-up

Postreduction care and follow-up

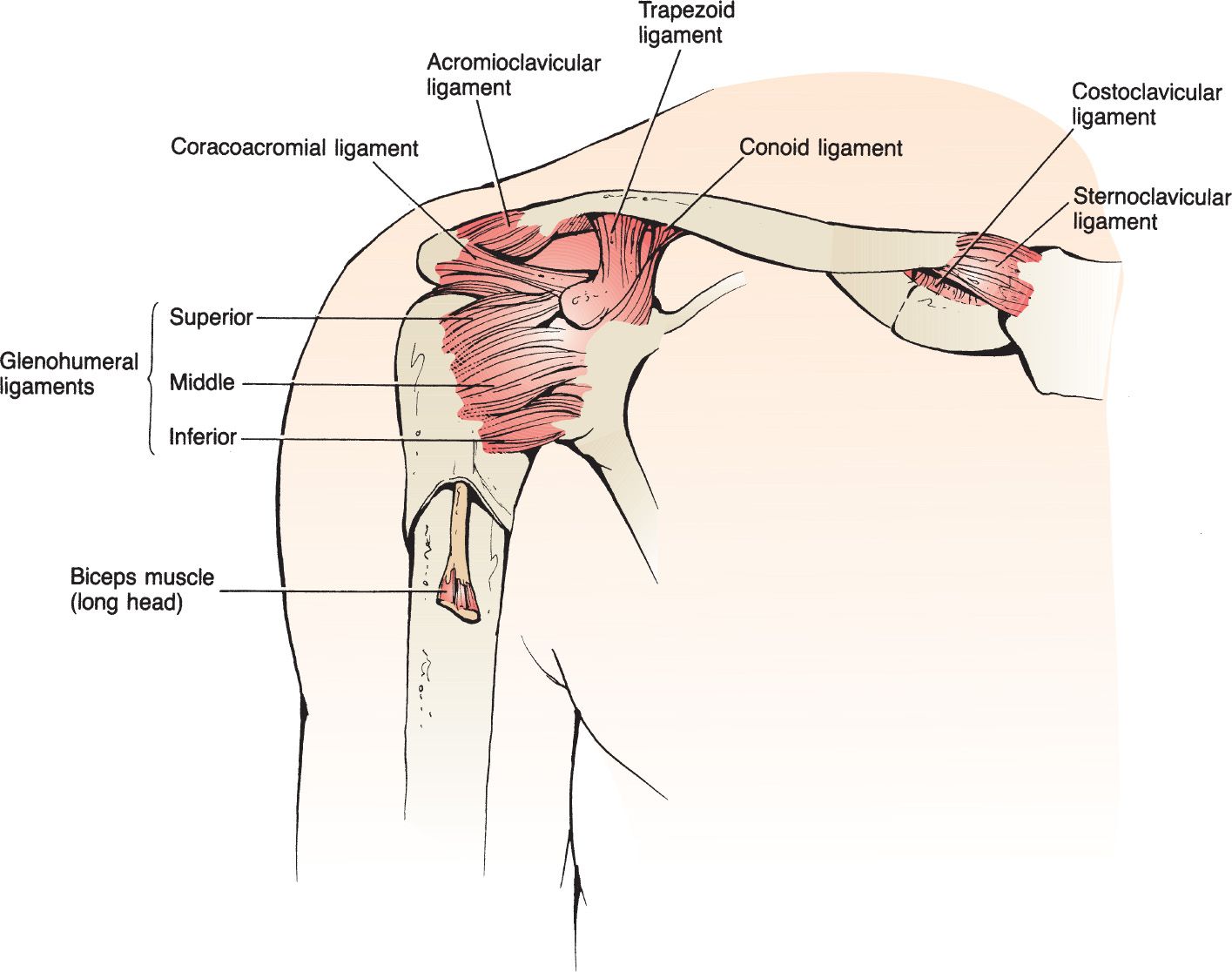

LANDMARKS—FIGURE 62.1

![]() Technique

Technique

![]() Physical Examination

Physical Examination

![]() Compare both the affected and unaffected extremities

Compare both the affected and unaffected extremities

![]() Perform a thorough neurovascular examination of the injured extremity

Perform a thorough neurovascular examination of the injured extremity

![]() A sensory deficit over the deltoid (the so-called sergeant’s-stripe pattern) or an impaired deltoid contraction implies an axillary nerve injury

A sensory deficit over the deltoid (the so-called sergeant’s-stripe pattern) or an impaired deltoid contraction implies an axillary nerve injury

![]() All major nerves to the arm should be assessed as injuries to the brachial plexus, ulnar, and radial nerves have been reported

All major nerves to the arm should be assessed as injuries to the brachial plexus, ulnar, and radial nerves have been reported

![]() Radiographs

Radiographs

![]() Obtain before reduction if the clinician is unsure of the position/type of dislocation or if there is concern for an associated fracture

Obtain before reduction if the clinician is unsure of the position/type of dislocation or if there is concern for an associated fracture

![]() May defer prereduction films if the clinician is confident of an anterior dislocation based on physical examination, the patient is <40, with a history of recurrent dislocations, and the mechanism of the dislocation is not associated with direct trauma

May defer prereduction films if the clinician is confident of an anterior dislocation based on physical examination, the patient is <40, with a history of recurrent dislocations, and the mechanism of the dislocation is not associated with direct trauma

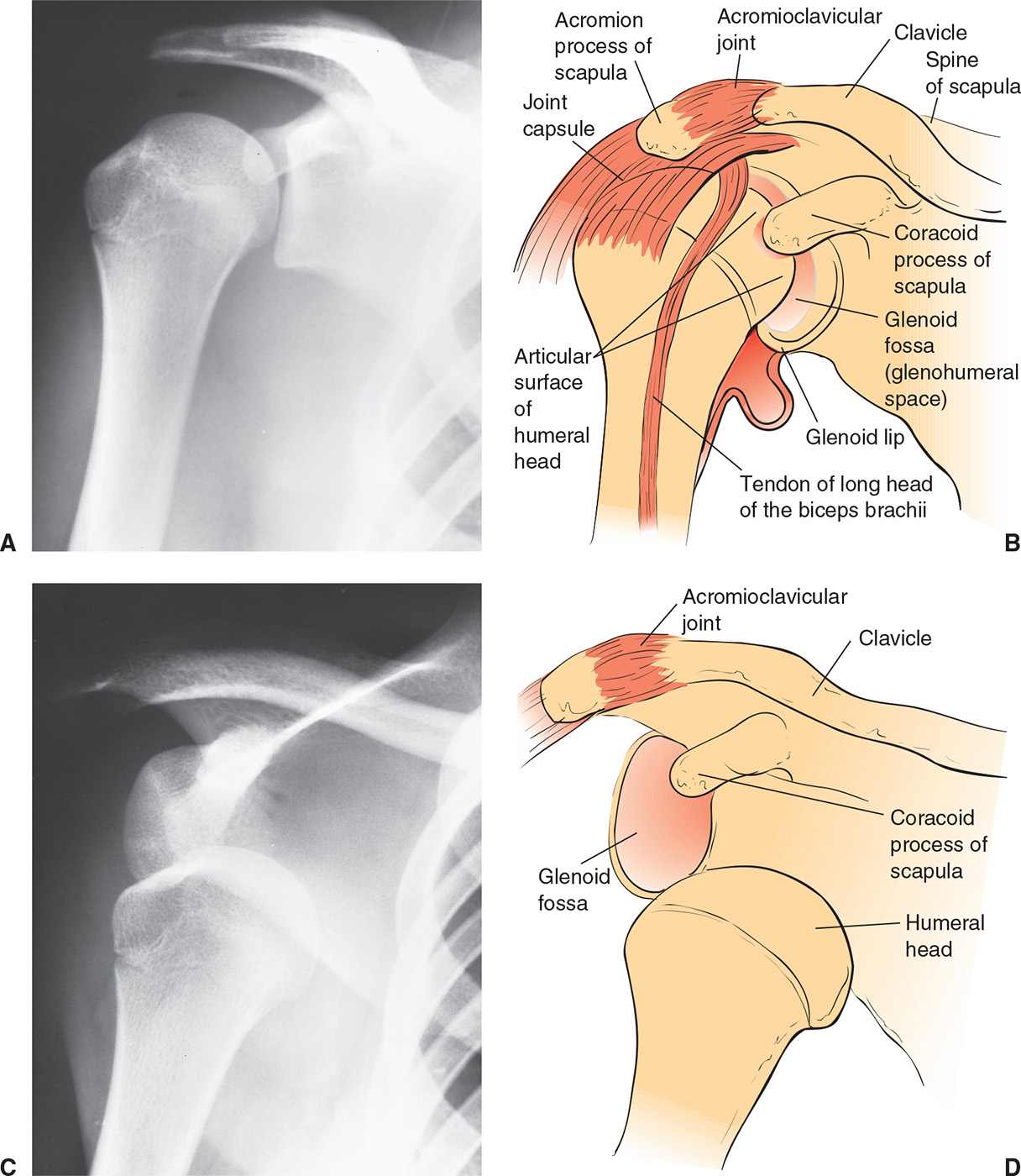

![]() Anteroposterior (AP), scapular Y, and axillary lateral view should be obtained

Anteroposterior (AP), scapular Y, and axillary lateral view should be obtained

![]() A single x-ray view should never be used to diagnose a shoulder dislocation

A single x-ray view should never be used to diagnose a shoulder dislocation

![]() In anterior dislocations, the humeral head is anterior in the axillary view (using the coracoid process as a point of orientation, and anterior to the center of Y in the trans-scapular view

In anterior dislocations, the humeral head is anterior in the axillary view (using the coracoid process as a point of orientation, and anterior to the center of Y in the trans-scapular view

![]() In posterior dislocations, the AP view may be diagnostic if it shows a partial vacancy of the glenoid fossa (vacant glenoid sign) and >6 mm space between the glenoid rim and humeral head (positive rim sign). The humeral head is posterior on axillary view and posterior to center Y on trans-scapular view.

In posterior dislocations, the AP view may be diagnostic if it shows a partial vacancy of the glenoid fossa (vacant glenoid sign) and >6 mm space between the glenoid rim and humeral head (positive rim sign). The humeral head is posterior on axillary view and posterior to center Y on trans-scapular view.

FIGURE 62.1 The essential anatomy of the shoulder. (From Sherman S. Shoulder injuries. In: Wolfson AB, ed. Harwood-Nuss’ Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2015:248, with permission.)

![]() Sedation, Analgesia, and Muscle Relaxation

Sedation, Analgesia, and Muscle Relaxation

![]() Adequate analgesia, muscle relaxation, and/or sedation help facilitate successful reduction

Adequate analgesia, muscle relaxation, and/or sedation help facilitate successful reduction

![]() A recent systematic review of intra-articular lidocaine vs procedural sedation showed no significant difference in reduction success rates, pain during reduction, and pain after reduction

A recent systematic review of intra-articular lidocaine vs procedural sedation showed no significant difference in reduction success rates, pain during reduction, and pain after reduction

![]() It is reasonable to attempt initial reduction with intra-articular local anesthetic; if unsuccessful, the clinician may consider procedural sedation for subsequent attempts

It is reasonable to attempt initial reduction with intra-articular local anesthetic; if unsuccessful, the clinician may consider procedural sedation for subsequent attempts

![]() Ensure that the patient relates the use of intra-articular lidocaine to the orthopedic surgeon during follow-up

Ensure that the patient relates the use of intra-articular lidocaine to the orthopedic surgeon during follow-up

![]() Intra-articular Injection of Lidocaine

Intra-articular Injection of Lidocaine

![]() Cleanse the shoulder with povidone–iodine solution

Cleanse the shoulder with povidone–iodine solution

![]() Insert the needle 2 cm inferiorly and directly lateral to the acromion, in the lateral sulcus left by the absent humeral head

Insert the needle 2 cm inferiorly and directly lateral to the acromion, in the lateral sulcus left by the absent humeral head

![]() Fill a 20-mL syringe with 1% lidocaine. Attach a 1.5-inch 20-gauge needle to the syringe (FIGURE 62.2).

Fill a 20-mL syringe with 1% lidocaine. Attach a 1.5-inch 20-gauge needle to the syringe (FIGURE 62.2).

![]() Withdraw to ensure you are not in a blood vessel prior to the injection of 15 to 20 mL of lidocaine into the joint space

Withdraw to ensure you are not in a blood vessel prior to the injection of 15 to 20 mL of lidocaine into the joint space

![]() Shoulder Reduction

Shoulder Reduction

![]() The guiding principle for all methods of reduction should be a gradual and gentle application of technique (FIGURE 62.3)

The guiding principle for all methods of reduction should be a gradual and gentle application of technique (FIGURE 62.3)

![]() The treating physician should be comfortable with several methods of reduction because no technique is 100% effective. The following techniques are described in this chapter:

The treating physician should be comfortable with several methods of reduction because no technique is 100% effective. The following techniques are described in this chapter:

![]() Stimson maneuver

Stimson maneuver

![]() Scapular manipulation

Scapular manipulation

![]() Traction–countertraction

Traction–countertraction

![]() Milch technique

Milch technique

![]() Hennepin or external rotation method

Hennepin or external rotation method

![]() Cunningham technique

Cunningham technique

![]() Posterior dislocation reduction

Posterior dislocation reduction

![]() Postreduction Care

Postreduction Care

![]() Obtain postreduction x-rays

Obtain postreduction x-rays

![]() Perform a postreduction neurovascular assessment and document the findings

Perform a postreduction neurovascular assessment and document the findings

![]() Position at discharge is controversial. Evidence regarding external rotation splinting is still evolving. Patients should be placed in a shoulder immobilizer or sling and swath for 2 to 3 weeks.

Position at discharge is controversial. Evidence regarding external rotation splinting is still evolving. Patients should be placed in a shoulder immobilizer or sling and swath for 2 to 3 weeks.

![]() Arrange orthopedic follow-up in 1 to 2 weeks

Arrange orthopedic follow-up in 1 to 2 weeks

![]() Older patients (<40) should have early follow-up within ~1 week to prevent adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder)

Older patients (<40) should have early follow-up within ~1 week to prevent adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder)

![]() Stimson Maneuver

Stimson Maneuver

![]() Patient is positioned prone with dislocated arm overhanging the bed

Patient is positioned prone with dislocated arm overhanging the bed

![]() Weight of 5 to 15 lb (initially supported by the physician) is strapped to the wrist of the affected extremity

Weight of 5 to 15 lb (initially supported by the physician) is strapped to the wrist of the affected extremity

![]() Traction is gradually exerted on the shoulder by slow and steady release of the physician’s support

Traction is gradually exerted on the shoulder by slow and steady release of the physician’s support

![]() Up to 30 minutes of sustained, steady traction may be necessary for reduction

Up to 30 minutes of sustained, steady traction may be necessary for reduction

![]() Reduction may be facilitated by delicate external rotation of the affected extremity

Reduction may be facilitated by delicate external rotation of the affected extremity

![]() Advantages: Can be performed by the lone practitioner without assistance

Advantages: Can be performed by the lone practitioner without assistance

![]() Disadvantages: Often requires more time and materials (weights and straps) than may be readily available (FIGURE 62.4). Not appropriate for all patients, particularly those with respiratory compromise.

Disadvantages: Often requires more time and materials (weights and straps) than may be readily available (FIGURE 62.4). Not appropriate for all patients, particularly those with respiratory compromise.

FIGURE 62.2 A, B: Normal shoulder joint. C, D: Anterior dislocation of the shoulder. (From Young GM. Reduction of common joint dislocations and subluxations. In: Henretig FM, King C, eds. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Procedures. Philadelphia, PA: Williams & Wilkins; 1997:1083, with permission.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree