Wendy L. Halm

Bursitis

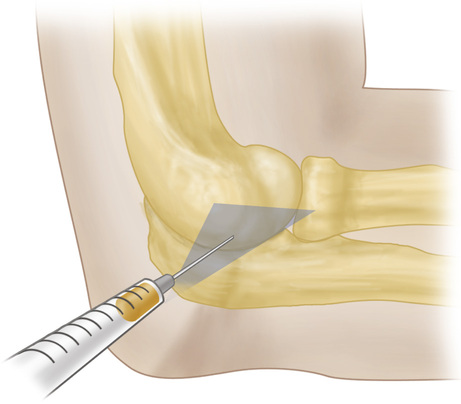

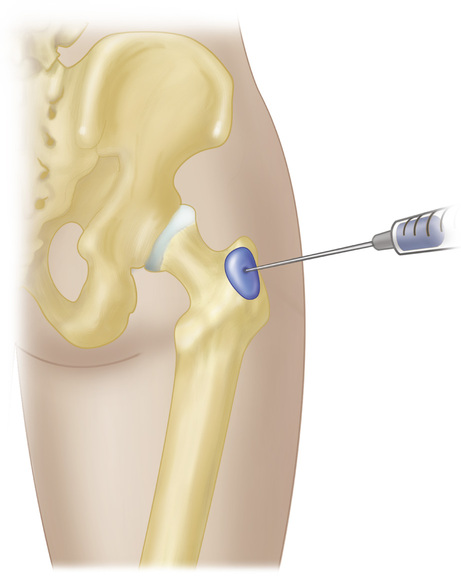

A bursa is a sac lined with synovial fluid, which provides lubrication and facilitates smooth movement between tissues of an extremity. Bursitis is a pathologic inflammatory disorder of the bursa caused by varied acute or insidious processes. These processes may include trauma or repetitive injury, autoimmune diseases, crystal deposits, and infection.1,2 Bursitis can result in mild pain or become a disabling condition. There are numerous bursae throughout the body, but only a few ever cause problems; these include bursae in the shoulder, hip, knee, elbow, and heel.

A diagnosis of bursitis is usually suspected on clinical grounds. Common features may include pain at motion and at rest; regional loss of range of motion; visible local swelling, especially if the affected bursa lies close to the surface; erythema and warmth over site; and tenderness to palpation.

Shoulder Bursitis

Definition and Epidemiology

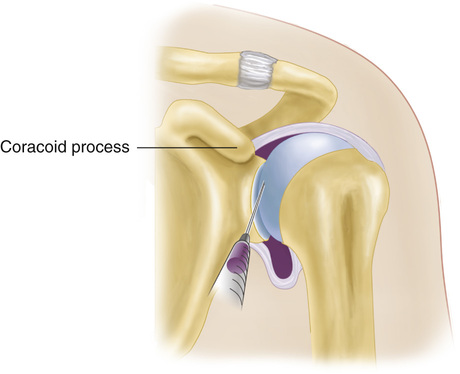

The four major bursae around the shoulder are the subacromial (subdeltoid), subcoracoid, subscapular, and scapular bursae. The subacromial bursa is located between the deltoid muscle and rotator cuff and extends under the acromion and coracoacromial arch. Subacromial bursitis is the most common type of bursitis.1,3 The overhead athlete is at risk for shoulder injury because of the mechanics associated with rapid shoulder elevation, abduction, and external rotation. If it is left untreated, the condition can progress to an irreversible impingement condition.4

Clinical Presentation and Physical Examination

Anterior or lateral shoulder pain with acute or insidious onset is the most common presenting complaint of patients with shoulder bursitis (see Chapter 187). The pain is exacerbated by overhead activities, and there may be a deep aching that interrupts sleep at night. Increased pain with active abduction and internal rotation of the arm plus tenderness below the acromion is demonstrated. Weakness can often be established with internal rotation. A complete neuromuscular examination with careful palpation and passive and active range of motion should be performed. In addition, a quick cervical spine examination can help rule out cervical pain with radiculopathy as the cause of the shoulder pain. The Neer and Hawkins impingement signs are the most sensitive and specific for subacromial bursitis. They indicate inflammation of the subacromial bursa and potentially the rotator cuff (Box 173-1).5,6 Clinicians should be aware of significant clinical diversity regarding the sensitivity and specificity of shoulder diagnostic tests.7–9

Diagnostics

Initial diagnostics should include plain radiography to exclude foreign body penetration, presence of arthritis (and to determine its extent), or fracture.5–7

• Plain radiography may demonstrate a hooked acromion, calcification of the supraspinatus tendon, osteopenia of the humerus greater tuberosity, and a distance of less than 5 mm between the acromion and humerus.6,10,11

Other diagnostics may include the following:

• Ultrasonography can be useful in the diagnosis but is operator dependent and more useful for the identification of rotator cuff pathology.12

• Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is now considered the gold standard and is widely used.

If the condition is related to an autoimmune or inflammatory process, serologic tests may reveal an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), rheumatoid factor, or antinuclear antibodies. If a septic cause is suspected, a white blood cell count as well as a Gram stain and culture of the bursa fluid should be obtained.11 If an aseptic condition is the cause of the bursitis, crystals may be observed in the bursa aspirate (Box 173-2).13,14

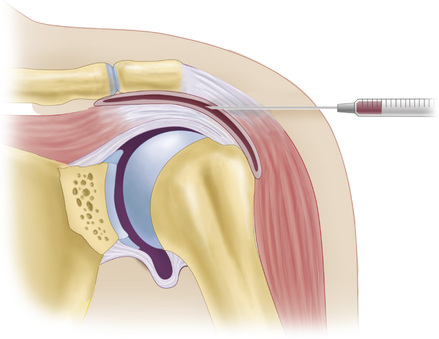

The impingement injection test is one method of differentiating between impingement and other shoulder disorders.3,4 With this test, 10 mL of 1% lidocaine (Xylocaine) is injected into the subacromial space; after 5 to 10 minutes, the maneuvers for the impingement signs are repeated. If the pain is reduced 50%, the shoulder pain is secondary to subacromial bursitis and tendinitis.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes fracture, dislocation, trauma, arthritis, adhesive capsulitis, rotator cuff tendinitis or tear, muscle strain, and referred pain. Causes of referred pain to the shoulder can include disorders of the cervical spine, chest cavity, breasts, axillary area, and abdomen.6

Management

![]() Orthopedic specialist referral is indicated for a demonstrated rotator cuff tear, for subacromial fibrosis, to assist in treatment of septic bursitis, or for excision of chronic enlarged bursa when indicated. A rheumatology consultation may be indicated for patients with underlying rheumatoid arthritis who have bursitis.

Orthopedic specialist referral is indicated for a demonstrated rotator cuff tear, for subacromial fibrosis, to assist in treatment of septic bursitis, or for excision of chronic enlarged bursa when indicated. A rheumatology consultation may be indicated for patients with underlying rheumatoid arthritis who have bursitis.

![]() Immediate emergency department referral is indicated for patients with symptoms consistent with septic bursitis or difficult-to-treat pain. Fever, erythema, warmth, and fluctuance (especially in conjunction with a patient history of diabetes, alcoholism, or impaired skin integrity) should heighten the clinician’s suspicion of septic bursitis.14

Immediate emergency department referral is indicated for patients with symptoms consistent with septic bursitis or difficult-to-treat pain. Fever, erythema, warmth, and fluctuance (especially in conjunction with a patient history of diabetes, alcoholism, or impaired skin integrity) should heighten the clinician’s suspicion of septic bursitis.14

The primary goals of treatment are the reduction of pain and improvement of range of motion. Except for autoimmune and septic shoulder conditions, treatment is directed at rehabilitation of the rotator cuff muscle group. Pain and inflammation may be managed with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in those without a relative contraindication. During the acute phase, rest and ice may be of benefit. Severe cases of shoulder bursitis may be managed with corticosteroid injections, guided by ultrasound or clinical landmarks. Injections should be limited to three or four injections per 12-month period, no less than 30 days apart.15 Additional therapeutic options may include physical therapy, ultrasound, electrical stimulation, acupuncture, or surgical intervention. Immobilization should be avoided because it may worsen the condition by causing adhesions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

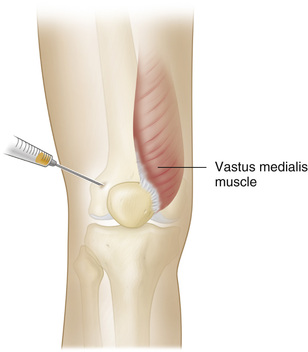

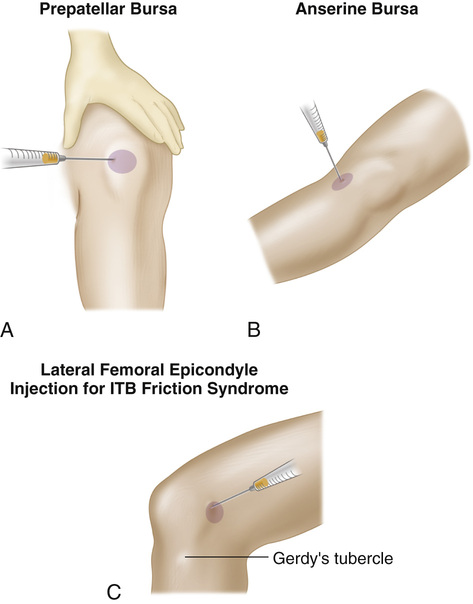

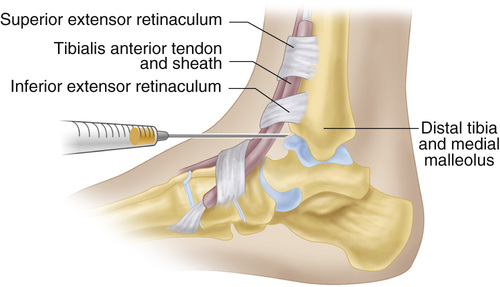

-inch needle for injection. A 5- or 10-mL Luer-Lok syringe is recommended.

-inch needle for injection. A 5- or 10-mL Luer-Lok syringe is recommended.