BURNS

ANGELA M. ELLISON, MD, MSc AND MARGARET SAMUELS-KALOW, MD, MPhil, MSHP

GOALS OF EMERGENCY CARE

As with any emergent situation, the goals of emergency care for the burned patient include the protection of the airway, and maintenance of breathing and circulation. For the burned patient in particular, this will include attention to the potential of inhalational injury and airway edema, consideration of burn location and need for escharotomy to ensure chest wall movement, and early and careful fluid resuscitation of burn shock. Beyond immediate resuscitative interventions, rapid resuscitation and appropriate wound care can significantly improve both mortality and functional outcomes. Concomitant control of pain is also an important aspect of care for the burned patient, both to prevent unnecessary discomfort and to permit required procedures. Finally, burn management aims at decreasing the risk of infection created by disruption of the skin barrier function, and facilitating healing and optimal cosmetic outcomes.

KEY POINTS

Burns should be described by estimated depth (superficial, partial thickness, or full thickness) and total body surface area involved (TBSA).

Burns should be described by estimated depth (superficial, partial thickness, or full thickness) and total body surface area involved (TBSA).

Significant burns are often accompanied by other injuries (including ocular, inhalational, or traumatic) that may require emergent assessment and treatment.

Significant burns are often accompanied by other injuries (including ocular, inhalational, or traumatic) that may require emergent assessment and treatment.

Full-thickness burns will be insensate due to destruction of the cutaneous nerves of the dermis.

Full-thickness burns will be insensate due to destruction of the cutaneous nerves of the dermis.

Severe burn injury requires intravenous fluid resuscitation, often calculated using the Parkland formula: IV fluid volume (mL) = (weight in kg) × (% TBSA burned) × 4. Half of this volume is given in the first 8 hours and the remaining half during the subsequent 16 hours, in addition to 24-hour maintenance fluids.

Severe burn injury requires intravenous fluid resuscitation, often calculated using the Parkland formula: IV fluid volume (mL) = (weight in kg) × (% TBSA burned) × 4. Half of this volume is given in the first 8 hours and the remaining half during the subsequent 16 hours, in addition to 24-hour maintenance fluids.

RELATED CHAPTERS

General Approach to the Ill or Injured Child

• A General Approach to Ill and Injured Children: Chapter 1

Signs and Symptoms

• Respiratory Distress: Chapter 66

Clinical Pathways

Medical, Surgical, and Trauma Emergencies

• Child Abuse/Assault: Chapter 95

INITIAL ASSESSMENT AND RESUSCITATION

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• Consider early intubation in patients with pharyngeal or airway swelling

• Inquire about the circumstances of the burn and determine the potential for associated injuries

• Maintain cervical spine precautions when managing the airway until spinal injury has been excluded

• Remember to remove sources of continued burn

Current Evidence

Globally, burns are the 11th leading cause of death in children aged 1 to 9 and the fifth most common cause of nonlethal injury. Data from the National Burn Repository (2012) suggest that burn injuries are more prevalent in minority children than would be expected based on demographics alone. Scald and contact burns are more common in the younger ages, with fire/flame more common in adolescent and adult patients.

Recent data suggest significantly improved survival for children with careful attention to burn care. In one study, half of children with burn injuries up to 90% TBSA survived their injuries, and research is ongoing into new methods for surgical management and pharmacologic treatment of burn wounds. Burn size and inhalational injury are two key predictors of survival in children.

Major systemic physiologic effects are seen in children with burns of more than 20% of body surface area (BSA). Burn injury causes increased capillary permeability and the release of osmotically active molecules to the interstitial space resulting in extravasation of fluid. Protein is lost from the vascular space to the interstitium during the first 24 hours. In patients with large burns, vasoactive mediators are released to the circulation and result in systemic capillary leakage. Edema develops in both burned and noninjured tissues. Circulating factors that depress myocardial function decrease cardiac output. Acute hemolysis of up to 15% of red blood cells may occur both from direct heat damage and from a microangiopathic hemolytic process. The profound circulatory effects of severe burns can result in life-threatening shock early after injury.

Goals of Treatment

High quality care is key for functional outcome and survival from burn injuries. Emergency management including prehospital care, assessment, resuscitation, treatment of potential inhalational injury, wound care, infection control, and appropriate admission are the first steps in a continuum of care that extends through hospitalization, potential surgical management, and rehabilitation. The unifying goal of these treatment modalities is to compensate for the physiologic effects of the burn and promote healing.

Clinical Considerations

Clinical Recognition

During the first few seconds after arrival, the physician must determine if a patient with burn injury requires aggressive therapy for major burns. In children with severe injuries, the evaluation and initial management take place simultaneously. Smoldering clothing or other sources of continued burning must be removed. Information about the circumstances of the burn and the potential for associated injuries should be sought from prehospital care providers, police, or family members, but this should not delay the initial treatment.

It is crucial to recognize inhalational injury as a cause of impending airway obstruction or respiratory failure. Clinical signs of potential inhalational injury include smoke exposure, burns on the face, singed nasal hairs, soot in sputum or visible in the upper airway, wheezing or rales.

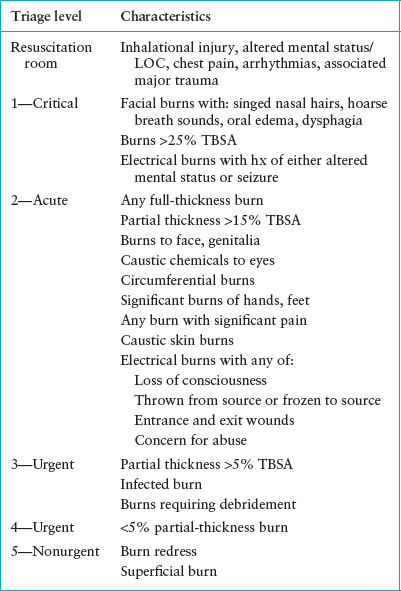

TABLE 112.1

BURN TRIAGE GUIDELINES

Triage Considerations

All children with nontrivial burns should be rapidly transported to a hospital setting. Once in the hospital, the triage process should take into account child’s age and medical history, the injury mechanism, and the surface area and depth of the burn. Children <2 years of age and those with significant comorbidities have a higher risk of burn-related complications. The physical response to burn injury and mortality prognosis appears to worsen significantly at around 30% TBSA burned, and so those children should be triaged to more rapid care.

One possible triage guideline based on a five-level emergency severity index (ESI) scale is shown in Table 112.1.

Clinical Assessment

Percentages. After the primary survey and initial stabilization, a systematic evaluation of the surface area and depth of burns follows. The rule of nines is used to estimate burn surface area in adolescents and adults. Each arm is approximately 9% TBSA, each leg is 18%, the anterior and posterior torso are each 18%, the head is 9%, and the perineum is 1%.

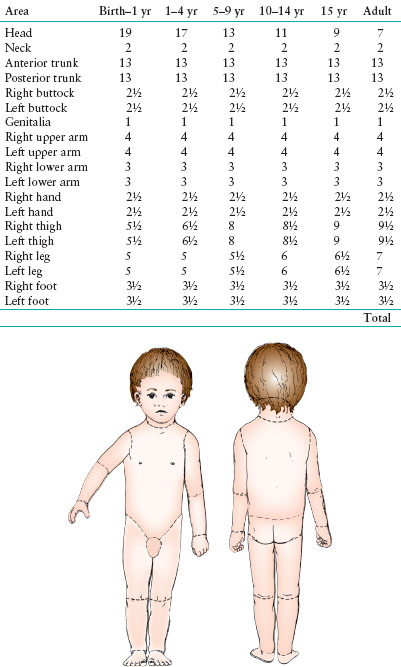

However, this rule cannot be applied to children because they have different body proportions. Young children have relatively larger heads and smaller extremities. Therefore, age-adjusted methods of estimating burn surface area have been developed (see Fig. 112.1). Alternatively, a child’s palm including the fingers is approximately 1% of BSA and this can be used to estimate the extent of scattered, smaller burns.

Areas of partial- and full-thickness injuries should be recorded on an anatomic chart and then a percentage of TBSA computed. First-degree burns are not included. BSA calculations are inexact, and some burns may progress over time, so BSA estimates should be reassessed.

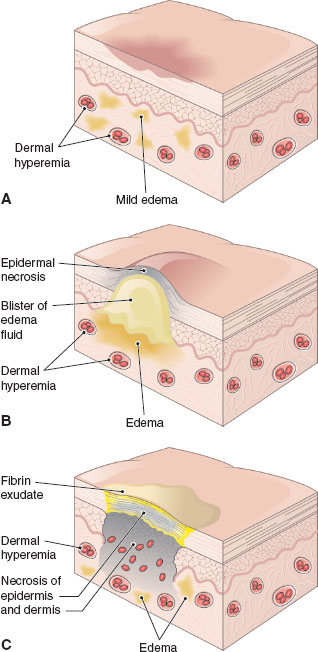

Description of Burn. The language used to describe burn severity has evolved over time, from a nomenclature of degrees to a description of the anatomic depth of the burn (see Fig. 112.2).

A superficial burn (formerly called first degree) occurs when the epidermis is injured but the dermis is intact. These burns are characterized by redness and a mild inflammatory response confined to the epidermis, without significant edema or bulla formation (see Fig. 112.3A). Superficial burns are not included in the calculation of burn surface area used for therapeutic decisions. These minor burns may be painful and usually resolve in 3 to 5 days without scarring.

In a partial-thickness burn (formerly called second degree), the dermis is partially injured and blistering is often present (see Fig. 112.3B). Increased capillary permeability, resulting from direct thermal injury and local mediator release, results in edema. These injuries are usually painful because intact sensory nerve receptors are exposed. The capillary network in the superficial dermis gives these burns a pink-red color and moist appearance. Healing occurs in about 2 weeks, and scarring is usually minimal.

Deep partial-thickness burns involve destruction of the epidermis and most of the dermis. Edema can lessen the exposure of sensory nerve receptors, making some partial-thickness burns less painful and tender, although there should be some intact pain sensation. Deep partial-thickness burns have a paler, drier appearance than superficial injuries, at times making them difficult to distinguish from full-thickness injury (see Fig. 112.3C). Thrombosed vessels often give deep partial-thickness burns a speckled appearance. Burns evaluated immediately may appear to be partial-thickness injuries and subsequently become full-thickness injuries, especially if secondary damage from infection, trauma, or hypoperfusion ensues. Deep partial-thickness burns can take many weeks to heal completely. Significant scarring is common and skin grafting may be necessary to optimize cosmetic results.

FIGURE 112.1 Estimation of surface area burned on the basis of age. This modification by O’Neill of the Brooke Army Burn Center diagram shows the change in surface of the head from 19% in an infant to 7% in an adult. Proper use of this chart provides an accurate basis for subsequent management of the child with burn injury.

Full-thickness burns (formerly called third degree) involve destruction of the epidermis and the entire dermis. They usually have a pale or charred color and a leathery appearance (see Fig. 112.3D). Important for recognition is the fact that destruction of the cutaneous nerves in the dermis makes them nontender, although surrounding areas of partial-thickness burns may be painful. Full-thickness burns cause a loss of skin elasticity. The burned skin cannot expand as tissue edema develops during the first 24 to 48 hours of fluid therapy. Circumferential or near-circumferential burns can therefore cause respiratory distress, abdominal compartment syndrome, and vascular insufficiency of the distal extremities. Full-thickness burns cannot reepithelialize and can heal only from the periphery. Most require skin grafting.

FIGURE 112.2 Skin burns are classified as superficial, partial thickness, or full thickness. A: Superficial burns affect only the outer layer of epidermis. B: Partial-thickness burns affect the lower layers of epidermis. C: Full-thickness burns destroy the entire layer of epidermis. (From Thomas H. McConnell. Nature of Disease. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013.)

Management

First Aid. Early cooling is accomplished by running cold water over the injured area. If performed in the first 60 minutes after injury, it not only stops ongoing thermal damage but also prevents edema, reducing progression to full-thickness injury. Applying ice directly to the wound is painful, and the extreme cold can worsen the injury. Parents should be reminded not to put grease, butter, or any ointment on the burn because these substances do not dissipate heat well and may contaminate the area. Intact blisters should not be broken during the prehospital phase. The burn should be covered with a clean cloth or bandage.

Prehospital. Prehospital care providers should focus initially on airway, breathing, and circulation, as they would for any other patient. Rapid transport to a hospital setting is crucial. Oxygen should be administered. The trachea should be intubated if there are signs of upper airway obstruction or impending obstruction. If transport time is likely to be prolonged, intravenous fluids should be started.

FIGURE 112.3 Examples of burns of various depths. A: Superficial: involves only the epidermis. B: Superficial partial thickness: partially injured dermis, with blistering. Note the pink-red color and moist appearance. C: Deep partial thickness: injury involves all of the epidermis and most of the dermis. Note the paler, drier appearance than superficial injuries. D: Full thickness: involves destruction of the entire epidermis and dermis. Not the area of pallor and charred color. These areas may also have a leathery appearance. (From Cohen BJ, Hull K. Memmler’s the human body in health and disease, 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer, 2014.)

Emergency Department Management. Specific management of major and minor burns is reviewed in the sections below. The final section also addresses management of burns with specific etiologies: inflicted, chemical, and electrical burns.

Preventing Infection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree