BREAST LESIONS

RAKESH D. MISTRY, MD, MS

Complaints related to the breast usually involve pain, discharge, and either discrete or diffuse enlargement. Presentation of a breast lesion in a pediatric patient in the emergency setting is uncommon; however, pediatric emergency physicians must be able to distinguish etiologies that require immediate intervention from those that are more appropriately handled by referral to a specialist or close follow-up with a general pediatrician. Fortunately, most breast lesions in children and adolescents are benign and self-limited. However, many patients and their families will benefit from reassurance that neoplastic diseases of the breast are extremely rare in all pediatric age groups. This chapter covers the spectrum of disorders that pediatric emergency physicians are likely to encounter, focuses on the diagnostic approach to breast lesions, and discusses the management of common etiologies.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

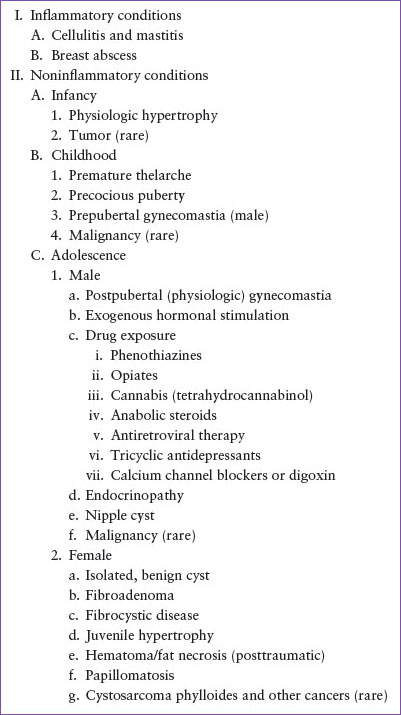

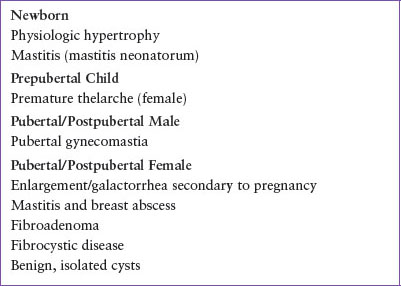

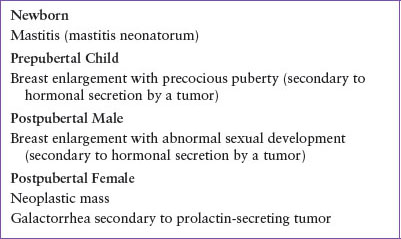

Breast lesions in children are typically divided into the following categories: infections, benign cysts or masses, malignant masses, abnormal nipple secretions, lesions associated with pregnancy and lactation, and miscellaneous causes, including both anatomic and physiologic entities (Table 11.1). A complete history and physical examination are essential to narrow the differential diagnosis and usually provides sufficient information to guide management. With few exceptions, most breast lesions require little diagnostic testing in the emergency department (ED) and typically can be evaluated using outpatient referral to an appropriate specialist. The commonly encountered disorders (Table 11.2) are almost always benign, but consideration must be given to potentially life-threatening processes (Table 11.3).

Breast Infections

Infection in the breast may take the form of a mastitis, cellulitis, or abscess. The incidence of breast infection occurs bimodally, with the early peak in the neonatal age group and the later, more common, peak in postpubertal females. Neonatal breast infection (mastitis neonatorum) most frequently presents in the first few weeks of life, commonly resulting from infection of the already enlarged breast bud produced by intrauterine maternal estrogen stimulation. As a result, mastitis neonatorum is more likely to occur in full-term, as opposed to premature infants. In some cases, excessive handling of the hypertrophied tissue by concerned caregivers may facilitate introduction of bacteria. The most common infecting organism is Staphylococcus aureus in >75% of cases; however, gram-negative enterics, as well as group A or group B streptococci may be isolated. More recent studies have demonstrated an increased incidence of community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA), and the presence of anaerobic bacteria in neonatal, adolescent, and adult breast infections.

The clinical presentation of neonatal breast infection is characterized by local signs of inflammation, such as edema, erythema, and warmth. Fever may be present in just 22% to 38% of cases and, although systemic symptoms are uncommon, the potential exists for seeding and associated invasive infections, including bacteremia, osteomyelitis, and pneumonia. For this reason, a complete evaluation for sepsis should be strongly considered in the presence of neonatal breast mastitis or abscess under the age of 2 months, especially in the setting of ill or toxic appearance. For older, well-appearing neonates, the emergency physician may elect to perform only a blood culture, and culture of purulent discharge, if present. Initial ED therapy consists of empiric broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotic for S. aureus, including CA-MRSA if indicated by local resistance rates, streptococcal organisms, and gram-negative enterics. Appropriate initial choices may include coverage for gram-positive organisms (vancomycin or clindamycin), with or without additional third-generation cephalosporins for gram-negative coverage. Subsequent antibiotic therapy can be guided by the results of a Gram stain and lesion culture. For cases where a breast abscess has developed, removal of purulent material is indicated. However, great care must be taken to avoid damaging the breast bud; therefore, surgical consultation is recommended, and needle aspiration is preferred to incision and drainage of the abscess cavity.

Breast infection in postpubertal females can be further classified as lactational or nonlactational. Lactational mastitis is discussed later in this chapter. Nonlactational mastitis and, less commonly, breast abscess, can develop in the central or peripheral regions of the breast usually resulting from introduction of skin bacteria into the ductal system. Infections in the central region of breast, proximal to the nipple, are more likely in the setting of obesity, nipple piercings, or poor hygiene, while peripheral mastitis is more likely to be associated with trauma or systemic illness. Other predisposing factors for mastitis include previous radiation therapy, foreign body, sebaceous cysts, hidradenitis suppurativa, and trauma to the periareolar area. Signs and symptoms of infection include local erythema, warmth, pain, and tenderness; dimpling of the overlying skin; and purulent nipple discharge. Systemic signs, including fever, are less commonly present. Organisms commonly implicated in this age group include both methicillin-sensitive and resistant S. aureus, streptococcal species, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas species, and anaerobic organisms such as Bacteroides species.

Recommended treatment for mastitis in the postpubertal female includes initiation of antistaphylococcal oral antibiotic therapy and warm compresses. Patients should be instructed to keep the area as clean and dry as possible, to wear a clean cotton bra to help prevent excessive sweating, and to avoid skin creams or talcum powders. The majority of patients may be managed as outpatients, but require a follow-up appointment in 24 to 48 hours to ensure the infection is improving. For patients with systemic symptoms, those who appear toxic, or demonstrate a lack of response to outpatient antibiotics, hospital admission for intravenous antibiotics is indicated. If a breast abscess is suspected, confirmation via ultrasonography is preferred. Breast abscesses should be drained via needed aspiration by a surgical specialist; incision and drainage are only occasionally necessary.

TABLE 11.1

BREAST ENLARGEMENT/MASSES

TABLE 11.2

COMMON BREAST LESIONS

TABLE 11.3

LIFE-THREATENING BREAST LESIONS

Benign Cysts and Masses

Enlargement of breast tissue may occur at any age, even in the neonatal period. As previously discussed, the male and female neonatal breast bud is hypertrophied in the first few weeks of life secondary to in utero maternal estrogen stimulation. This is a normal physiologic response that abates over time; treatment is not required and caregivers should be instructed to avoid manual stimulation. In preschool age girls, a temporary unilateral or bilateral enlargement of the breast bud may occur. This is typically consistent with isolated premature thelarche in the absence of other manifestations or development of secondary sexual characteristics: Reassurance should be provided as the enlargement will most likely spontaneously resolve, though close follow-up with a primary care physician is prudent. The presence of breast enlargement in the setting of secondary sexual characteristics, such as pubic hair (precocious puberty) in girls, or any breast enlargement in young boys (prepubertal gynecomastia), is atypical, and a specific cause should be aggressively pursued. Careful history and examination focused on the presence of adrenal, ovarian, or hypothalamic pathology, including hormone-secreting tumors and intracranial tumors, are indicated in these cases. Recent medication usage should be reviewed as several medications can cause gynecomastia (Table 11.1). Unless an intracranial mass is suspected, most children can be referred for outpatient workup with an experienced physician or endocrinologist.

Fibroadenomas are the most common benign breast lesion (>75%) in the adolescent age group. When present in adolescent girls, these lesions are sometimes called juvenile fibroadenomas. Fibroadenomas are usually discovered by self-examination and present as well-circumscribed, solitary, mobile, rubbery, mildly tender masses of the upper outer quadrants of the breast that are typically <2 to 3 cm in size. These lesions are benign and do not require extensive evaluation; ultrasonography is most helpful and is recommended in the ED to secure the diagnosis, and exclude more severe pathologies. Fibroadenomas can be observed over time, and reassurance that the exceedingly low malignant potential should be provided. Treatment is required for giant fibroadenomas (>5 cm), referral to a pediatric or breast surgeon for excisional biopsy is preferred to prevent destruction of healthy breast tissue.

Fibrocystic disease is a benign, progressive process generally seen in women during the reproductive years, but may also present in adolescence. Fibrocystic masses may be solitary or multiple, unilateral or bilateral, feel nodular within the breast tissue, and are most prominent in the upper outer quadrants of the breast. Frequently, presentation is that of cyclically painful masses, that change in size or nodularity during the course of the menstrual cycle, with the maximal symptoms during the premenstrual phase. Nipple discharge is rarely present and is typically nonbloody, green, or brown. Importantly, in the adolescent population, these lesions are not precancerous. Breast ultrasonography can be used to confirm the diagnosis; neither needle aspiration nor breast biopsy is required. Treatment is largely symptomatic with breast support, nonsteroidal analgesics, and avoidance of caffeine. Oral contraceptive agents can reduce symptoms in severe cases for adults, but are not typically prescribed for fibrocystic disease in adolescence. Follow-up and subsequent evaluation by a primary care physician is recommended; referral to a surgeon for needle aspiration or excisional biopsy is indicated for painful, large, solitary lesions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree