INTRODUCTION

The most common breast complaints in the ED involve breast pain, breast mass, nipple discharge, infection, or postoperative complications. Approximately 30% of women will present to a physician with a chief complaint related to the breasts.1 Although the problems are rarely emergent except when systemic symptoms such as fever are present, concerns about the potential for breast cancer contribute to patient anxiety.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Adult breast is composed of approximately 20% glandular tissue, and the remaining breast volume consists of fat and connective tissue that give the breast its characteristic texture and shape. Glandular lobules drain into lactiferous ducts, which converge and open at the nipple. In nonpendulous breast, the nipple is an important landmark located over the fourth intercostal space.

Normal breast tissue extends from the sternocostal junction medially to the midaxillary line laterally and from the second to the sixth ribs in the midclavicular line. An axillary tail of breast tissue often extends into the axilla. Blood supply arises from the internal mammary, lateral thoracic, thoracodorsal, and subscapular arteries, whereas venous drainage starts in the subareolar plexus and empties into the intercostals, internal mammary, and axillary veins. Lymphatic drainage of the breast is primarily to the axilla, with a small portion going to internal mammary lymph nodes.

Cyclic variances in estrogens, progesterone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and luteinizing hormone signal stromal and glandular changes in breast physiology.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Ask the patient about onset of any mass or pain, location of the affected area, and duration of the symptoms. Complaints that vary with menses suggest a benign cause, whereas cancers are often asymptomatic. Radiation of the pain to any other body site is particularly important when a malignancy is suspected. The presence of symptoms in the contralateral breast parenchyma is also more reassuring for a benign diagnosis. Assess the color and consistency of any nipple discharge, although the color of the discharge does not differentiate a benign from a malignant process. Changes that the patient notes on breast self-examination may be significant and should be correlated with the menstrual cycle. Ask about family history, specifically about first-degree relatives with breast cancer and other risk factors (delay of childbearing to after age 30 years, biopsy confirmation of atypical hyperplasia, or history of chest irradiation). However, most women who develop breast cancer have no obvious risk factors beyond the two strongest factors, namely, female gender and age. More than 50% of breast cancers are diagnosed in women ≥65 years of age, and women <30 years of age are diagnosed with <1% of all breast cancers.2

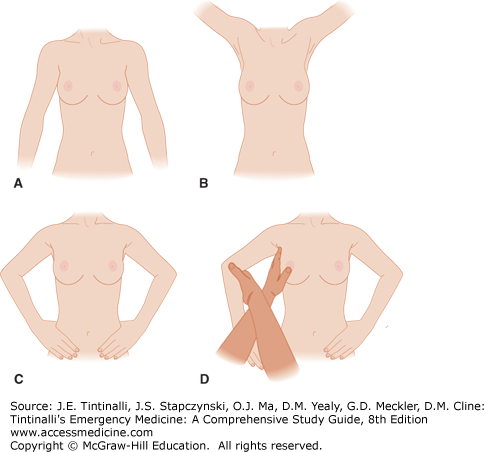

The breast examination (Figure 104-1) includes both inspection and palpation. Compare the breasts with the patient sitting upright, and note any breast asymmetry or skin dimpling. Subtle abnormalities in the lower quadrants may be accentuated by having the patient raise her arms above her head. Also examine the axillae, including the mammary tail and lymph nodes, in the sitting position. Perform the rest of the examination with the patient supine and ipsilateral hand behind the head. Examine the upper outer quadrant of each breast with extra care, because about half of breast carcinomas originate in that area, with a higher propensity for left-sided involvement.2,3 Examine the nipple-areola complex with gentle manipulation to detect subareolar masses and latent nipple discharge. Women with breast augmentation may be challenging to examine, but give attention to tissue changes or deviation of the implant.

DISORDERS OF THE LACTATING BREAST

Any inappropriate secretion of milky discharge from the breast is called galactorrhea. Galactorrhea often results from abnormally elevated levels of prolactin, although some women have normal prolactin levels on testing. Hyperprolactinemia may be caused by inadequate inhibition of secretion or increased production of prolactin. Causes of elevated prolactin levels are listed in Table 104-1.

| Physiologic causes | Sleep, stress, exercise, volume depletion, intercourse or orgasm, pregnancy, breast stimulation, seizures |

| Abnormal stimulation of the chest wall | Surgery, trauma, herpetic infection |

| Damage to or disruption of the pituitary stalk | — |

| Endogenous hypothalamic-pituitary signaling | — |

| Neoplasms | Prolactinomas, renal cell carcinoma, lymphoma, craniopharyngioma, bronchogenic carcinoma, hydatidiform mole |

| Medications | Antidepressants (monoamine oxidase inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants), antihypertensives (atenolol, methyldopa, reserpine, verapamil), antipsychotic phenothiazines, antihistamines, herbs and vitamin supplements (anise, fennel, nettle, clover, thistle, fenugreek seed), amphetamines, cocaine, opioids, marijuana |

| Systemic disease | Chronic renal failure, hypothyroidism, hypercortisolism (Cushing’s disease), acromegaly |

Prolactinomas, benign anterior pituitary neoplasms, are distinguished by symptoms of galactorrhea, amenorrhea, hirsutism, facial acne, visual field deficits, and headaches. Chronic renal failure results in a diminished capacity to clear circulating prolactin. Hypothyroidism causes increased levels of thyrotropin-releasing hormone, which result in increased pituitary secretion of prolactin. Hypercortisolism (Cushing’s disease) and acromegaly due to elevated growth hormone levels are both associated with galactorrhea.

Evaluation of the patient with galactorrhea focuses on any history of associated menstrual abnormalities and the presence of acne, hirsutism, infertility, or libido changes. Symptoms of increased intracranial pressure and hypothyroidism should be investigated. All medications and dietary supplements should be reviewed.

The physical examination includes evaluations of the visual fields, breasts, skin, and thyroid gland. ED studies include a urine or serum pregnancy test and may include neuroimaging (CT or MRI) and neurosurgical consultation if there is concern for an intracranial mass. Treatment for galactorrhea, other than the discontinuation of a medication suspected to be causative, is deferred to the primary care physician or the follow-up specialist.

Breast engorgement usually presents on the third to fifth postpartum day, with symptoms of painful, hard, and enlarged breasts. The pain may be accompanied by nausea and low-grade fever. Engorgement results from inadequate removal of milk from the breast. This may be due to infant separation, sore nipples, or improper breastfeeding techniques.4 Ensuring proper latch-on while breastfeeding or pumping usually alleviates the pain and allows for decompression of the nipple-areola complex. Warm showers or manual massage may also help facilitate milk letdown and relieve pain due to engorgement.

Nipple irritation or soreness is common and usually caused by poor positioning or latch-on techniques. Other causes include trauma, plugged ducts, candidiasis, and inflammatory skin disorders. Purified lanolin cream, analgesics, and breast shields may help facilitate healing. There may be some benefit to applying expressed breast milk to nipples.4,5 There is controversy regarding the role of antifungals for treatment of breast and nipple pain associated with breastfeeding.6 Reynaud’s phenomenon can cause nipple pain in some women and may respond to topical nefedipine.7

Puerperal mastitis, or endemic mastitis, presents with severe pain, tenderness, swelling, and redness. Patients may also develop fever, chills, and myalgias. Mastitis is more common in primiparous women in the first few weeks to months of breastfeeding. There is often an associated history of nipple pain or breakdown and inadequate milk drainage that leads to bacterial colonization and infection. Differentials include marked breast engorgement, clogged milk duct, and inflammatory carcinoma, a rare condition.

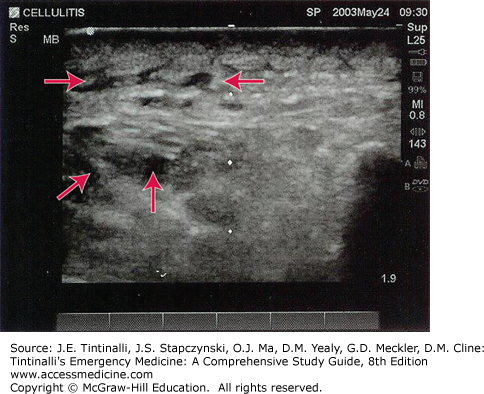

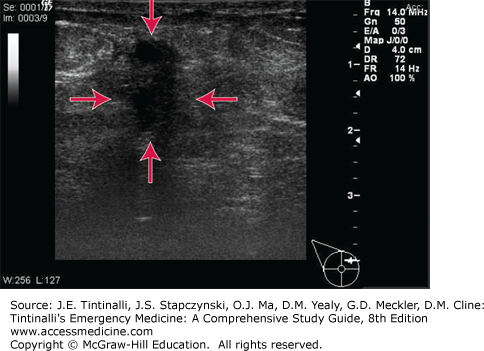

Mastitis, like other inflammatory processes, has the US appearance of hypoechoic fluid surrounding subcutaneous fat lobules without a discrete fluid collection (Figure 104-2), in contrast to abscess (Figure 104-3), which presents as a hypoechoic (dark) fluid collection in the tissue with the absence of vascular signals.

Puerperal mastitis is caused by Staphylococcus aureus in 40% of cases, although Escherichia coli and Streptococcus species are also known pathogens. Mastitis can be associated with S. aureus nasal carriage in the breastfeeding infant.8 Consider community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections associated with puerperal mastitis and abscess.5 There is no need to interrupt breastfeeding. Treatment requires frequent analgesia, breast emptying, and early antibiotics with antistaphylococcal penicillins or cephalosporins (Table 104-2). Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim cannot be given to lactating mothers with infants <2 months old. If the infection fails to respond rapidly to antibiotics, suspect abscess and broaden antibiotic coverage.

| Signs and Symptoms | Treatment | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Puerperal mastitis | Erythematous area on breast with area of well-localized pain Fever, chills, myalgias, flulike symptoms | Frequent breast emptying Routine hand washing prior to breast manipulation Analgesia Antibiotics: Dicloxacillin, 500 milligrams four times a day for 10–14 d or Cephalexin, 500 milligrams four times a day for 10–14 d or Clindamycin, 300 milligrams four times a day for 10–14 d | Occurs during first few month or weeks postpartum. Breastfeeding may continue. Early antibiotics and milk drainage are cornerstone of treatment. Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|