INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

The phylum Arthropoda is the largest division of the animal kingdom. The phylum includes insects (bees, wasps, hornets, flies, mosquitoes, bedbugs, fire ants, caterpillars, fleas), arachnids (spiders, scorpions, chiggers, ticks), and crustaceans (shrimp, lobsters, crabs). Venomous bites and stings from arthropods are a significant worldwide problem.1 In the United States, the American Association of Poison Control Centers reported almost 50,000 cases of exposures to arthropods in 2012.2 Some of these were listed as resulting in major or severe reactions, including severe pain, neurotoxicity, or other signs and symptoms. Fatalities among these exposures are rarely reported to poison centers and usually result from allergic reactions to Hymenoptera stings. Toxic reactions to multiple stings by members of the order Hymenoptera and severe systemic allergic reactions to one or more stings or bites of other insects, such as deerflies, blackflies, horseflies, and kissing bugs, can all present as emergency, life-threatening situations.3 Other arthropod bites and envenomations merit review either because they cause specific organ system toxicity or because they can result in transmission of infectious disease. This chapter discusses the most common and serious arthropod bites and envenomations. Tick bites are discussed in the “Tickborne Zoonotic Infections” section of chapter 160, “Zoonotic Infections: Tickborne Zoonotic Infections.”

HYMENOPTERA (WASPS, BEES, AND ANTS)

More fatalities result from stings by these insects than by stings or bites by any other arthropod. There are three major subgroups or superfamilies of medical importance: (1) Apidae, which includes the honeybee and bumblebee; (2) Vespidae, which includes yellow jackets, hornets, and wasps; and (3) Formicidae, or ants.

Apids, such as honeybees and bumblebees, are usually docile, stinging only when provoked. A female honeybee is capable of stinging only once (male bees have no stinger), because its stinger has multiple barbs that cause the sting apparatus to detach from the bee’s body, which leads to evisceration and eventual death.

Africanized honeybees, or so-called killer bees, are now found in most of the southern and warmer regions of the United States extending from coast to coast. These bees are hybrids of African bees that escaped from laboratories in Brazil during the 1950s and have successfully spread northward along the coasts and temperate regions of the continent. Their venom is no more toxic than that of their American counterpart, but Africanized hybrid honeybees are more aggressive, and a hive can respond to a perceived threat with >10 times the number of bees that respond from a hive of typical North American bees. An attack from Africanized bees can lead to massive stinging, resulting in multisystem damage and death from severe venom toxicity.4,5

Most of the allergic reactions reported each year due to Hymenoptera occur from vespid (wasp, hornet, and yellow jacket) stings. These arthropods nest in the ground, in trees, or in walls; have volatile tempers; and may be disturbed by work taking place around the nest. As with bees, only the females have adapted a stinger from the ovipositor on the posterior aspect of the abdomen. Although vespids also possess barbed stingers, they have the ability to withdraw their stingers from the victim, which permits multiple stings.

Hymenoptera venom contains several components.6 Although histamine is one of those components, other substances are now recognized as more important. Melittin, a known membrane-active polypeptide that can cause degranulation of basophils and mast cells, constitutes >50% of the dry weight of bee venom. Protein enzymes such as phospholipase and hyaluronidase may account for most systemic reactions.7,8 Because all Hymenoptera share many of these components, cross-sensitization may occur in individuals allergic to one species. Yellow jacket venom is perhaps the most potent sensitizer.

The most common response to Hymenoptera venom is a local reaction: pain, slight erythema, edema or urticaria, and pruritus at the sting site. A severe local reaction may involve one or more neighboring joints. A local reaction occurring in the mouth or throat can produce airway obstruction. Stings around the eye or on the lid may result in the development of an anterior capsule cataract, atrophy of the iris, lens abscess, perforation of the globe, glaucoma, or refractive changes. When local reactions become increasingly severe, the likelihood of future systemic reactions appears to increase, and if skin test results are positive, immunotherapy may be warranted.

Anaphylaxis Symptoms range on a continuum. Criteria for anaphylaxis are presented in Table 211-1, and detailed discussion of anaphylaxis is provided in chapter 14, “Anaphylaxis, Allergies, and Angioedema.” Most reactions develop within the first 15 minutes, and nearly all occur within 6 hours. Initial mild symptoms may progress swiftly to shock. There is no correlation between systemic reaction and the number of stings. Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea; light-headedness and syncope; involuntary muscle spasms; edema without urticaria; and, rarely, seizures. Respiratory distress and cardiac arrest can result. Urticaria and bronchospasm do not need to be present. In general, the shorter the interval between the sting and the onset of symptoms, the more severe is the reaction. Fatalities that occur within the first hour after the sting usually result from airway obstruction or hypotension.

1. Acute onset of an illness (minutes to several hours) with involvement of the skin and/or mucosal tissue (e.g., hives/urticaria, pruritus, flushing, swollen lips, tongue, or uvula) associated with at least one of the following:

|

2. Two or more of the following that occur rapidly after exposure to a likely allergen for that patient (minutes to several hours):

|

| 3. Anaphylaxis should be suspected when patients are exposed to a known allergen and develop hypotension |

Renal and hepatic failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation can result from massive bee stings. Creatine phosphokinase concentrations can reach 100,000 IU/L or more in cases in which rhabdomyolysis occurs from direct venom toxicity.5 Toxic reactions are believed to occur due to a direct multisystem effect of the venom. Symptoms usually subside within 48 hours but may last for several days in severe cases, and some effects, such as rhabdomyolysis, can be delayed. We recommend hospital admission or observation for victims with >100 stings, for those with substantial comorbidities, and for those at extremes of age.

Delayed Reaction A delayed reaction, appearing 5 to 14 days after a sting, consists of serum sickness–like signs and symptoms of fever, malaise, headache, urticaria, lymphadenopathy, and polyarthritis.9 Frequently, the patient has forgotten about the encounter and is puzzled by the sudden appearance of symptoms. This reaction is believed to be immune complex mediated.

Unusual Reactions Infrequently, a reaction to Hymenoptera venom produces neurologic, cardiovascular, and urologic symptoms, with signs of encephalopathy, neuritis, vasculitis, and nephrosis. Guillain-Barré syndrome has been reported as a possible consequence of a Hymenoptera sting. Identification of the offending insect can be difficult, except for the honeybee, which predictably leaves its stinger with venom sac attached in the lesion. In general, definitive insect identification is unnecessary, because signs and symptoms of envenomation are similar for all species of Hymenoptera. If edema persists at the sting site, then consider secondary cellulitis. Severe local reactions on the foot or ankle can be misdiagnosed as gout if the insect sting is not visible.

If the bee stinger is present in the wound, remove it. Although conventional teaching suggested scraping the stinger out to avoid squeezing remaining venom from the retained venom gland into the tissues, involuntary muscle contraction of the gland continues after evisceration, and the venom contents are quickly exhausted. Immediate removal is the important principle, and the method of removal is irrelevant. Wash the sting site thoroughly with soap and water to minimize infection. For local reactions, intermittent application of ice packs at the site diminishes swelling and delays the absorption of venom while limiting edema. Oral antihistamines and analgesics may limit discomfort and pruritus. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be effective in relieving pain. Standard doses of opioid analgesics also can be administered. If edema is significant, elevation and rest of the affected limb should limit swelling unless secondary infection develops, in which case antibiotics are necessary. In local tissue reactions, there is often significant inflammatory erythema and swelling, which make it difficult to distinguish from infection. As a general rule, infection is uncommon. We recommend hospital admission or observation for victims with >100 stings, for those with substantial comorbidities, and for those at extremes of age.

Although the initial signs and symptoms of a systemic reaction may be mild, the victim’s condition can deteriorate rapidly in a matter of minutes. Administer IM epinephrine, 0.3 to 0.5 milligram (0.3 to 0.5 mL of 1:1000 concentration) in adults and 0.01 milligram/kg in children (up to 0.3 milligram). Massage the injection site to hasten absorption. To avoid mishaps in dosing, many EDs now stock adult and pediatric EpiPens, which provide a standard adult or pediatric dose (EpiPen, 0.3 milligram epinephrine; EpiPen-Jr, 0.15 milligram epinephrine for children <30 kg). Provide aggressive fluid resuscitation with crystalloids. Antihistamines, histamine-2 receptor antagonists, and steroids are also commonly given. See chapter 14 for detailed discussion. Antivenoms have been studied for the treatment of mass bee attacks but are not yet commercially available.10

Results of skin tests and radioallergosorbent tests are not fully reliable for determining which patients are at risk for systemic reaction during future encounters with Hymenoptera (Table 211-2) but should be coupled with information from the clinical history.8,11 Patients with negative test results may have been sensitized by the skin tests themselves. Every patient who has had a systemic reaction should be provided with an insect sting kit containing premeasured epinephrine and should be carefully instructed in its use. The physician should stress that the patient must inject the epinephrine at the first sign of a systemic reaction. Physicians should also advise their patients who are allergic to insects to wear identification (e.g., medical alert tags) describing their severe allergy. They should also be advised to follow up with an allergist.

| Type of Reaction | Risk of Systemic Reaction on Subsequent Stings | Perform Skin Testing? | Results of Skin Testing | Recommended Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never stung | Minimal | No | None | |

| Local reaction | ||||

| Minor local reaction: immediate pain, swelling, and itching at sting site, resolves in 1 d | Minimal | No | None | |

| Extensive local reaction: swelling develops 24–48 h after sting and resolves in 3–7 d | <10% | No | Epinephrine syringe | |

| Systemic reaction | ||||

| Adult (urticaria, angioedema, anaphylaxis) | High | Yes | + | Venom immunotherapy plus epinephrine syringe |

| – | Epinephrine syringe | |||

| Child (urticaria and mild angioedema) | Low | Yes | + | Venom immunotherapy or epinephrine syringe |

| – | Epinephrine syringe | |||

| Child (anaphylaxis) | Moderate | Yes | + | Venom immunotherapy plus epinephrine syringe |

| – | Epinephrine syringe | |||

There are five known species of fire ants (Solenopsis) in the United States: the native species Solenopsis aurea, Solenopsis geminata, and Solenopsis xyloni, and at least two imported species, Solenopsis invicta and Solenopsis richteri. These two imported species entered the United States through Mobile, Alabama, in the 1930s, have now become well established throughout the Gulf Coast states, and are spreading throughout the southwest.12 Fire ants inhabit loose dirt and breed 9 to 10 months of the year. One mature nest can produce 200,000 ants during a 3-year period, which accounts for rapid spread. The venom of the fire ant is almost entirely an insoluble alkaloid. There is possible cross-reactivity between the venoms of fire ants and those of other Hymenoptera, and individual stings may produce systemic toxicity in sensitized individuals.

Fire ants are characterized by their tendency to swarm when provoked, and they may attack in great numbers. Fire ants in a swarm most often position themselves on their victim and sting simultaneously in response to an alarm pheromone released by one or several individuals. Immobilized or elderly patients can become rapidly covered by swarms, with multiple severe stings or death.13 Each sting usually results in a papule that becomes a sterile pustule in 6 to 24 hours. Localized necrosis, scarring, and secondary infection can result. Rarely, a systemic reaction manifested by urticaria and angioedema can occur. Fatalities and other severe reactions have been reported to occur rapidly following single stings from ants, but most occur in patients with a history of prior venom allergy and prior cardiopulmonary disease, and injectable epinephrine was not given.14,15 Rhabdomyolysis and renal failure have also been reported after massive fire ant stings.16

Estimated hypersensitivity to fire ant venom occurs in 16% of the general population, with some crossover with those sensitized to the stings of other Hymenoptera. Treatment of fire ant stings consists of local wound care.13 In systemic reactions, treat for anaphylaxis. Desensitization may be necessary in patients exhibiting potentially life-threatening reactions to these arthropods. The wearing of socks or cotton tights seems to provide more protection from fire ant stings than the use of insect repellants.17

SPIDERS (ARANEAE)

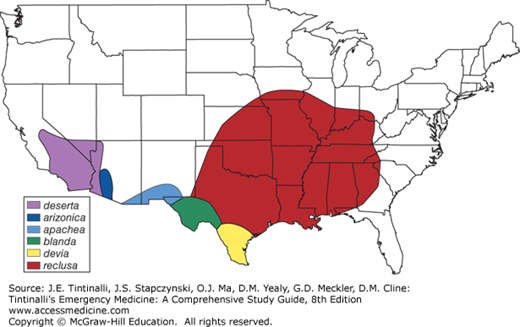

Although nearly 40,000 species of spiders have been described worldwide, medically significant envenomations have been described in only a few dozen (Table 211-3). Spiders are carnivores, and venom probably evolved for paralyzing prey. The vast majority of spiders pose little harm to humans because their venom-injecting fangs are too small to penetrate human skin, the amount of venom injected is too little to produce toxicity, or the venom itself has little effect on mammalian cells. Even if a reaction is elicited, it is often local, and systemic toxicity is confined to a few specific species (Table 211-3 and Figure 211-1).

| Spider | Bite Features | Complications | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loxosceles: brown recluse spider, corner spider (worldwide distribution) | Painless bite, usually firm erythematous lesion that heals with little or no scar over days to weeks | Occasional hemorrhagic blister at 24 h; dermatonecrosis; systemic effects rare, mostly in in children, at 24–72 h | No validated treatments |

| Widow spider: black widow, redback, button spider (worldwide distribution); | Pinprick bite; pain can spread to entire extremity; target lesion 1–2 cm | Acetylcholine and norepinephrine release; muscle cramps extending to trunk, back, and abdomen; hypertension, tachycardia | Latrodectus antivenom, species specific; derived from horse serum; Fab antivenom available in Mexico |

| Armed spider: banana spider (Central and South America) | Intense pain at bite site | Severe pain, sympathetic and parasympathetic effects; priapism; vertigo, visual disturbances | Antivenom available in Brazil |

| Funnel-web spider (Australia) | Severe pain, with wheal and erythema at site; very rapid envenomation | Parasympathetic effects, muscle fasciculation; pulmonary edema; cerebral edema; death can occur within minutes | Compressive elastic bandage; funnel-web spider antivenom |

| Tarantula (worldwide) | Painful bite with local erythema and edema | Barbed hairs can penetrate cornea and conjunctivae; contact dermatitis from hairs | Ophthalmology consult for red eye and pain |

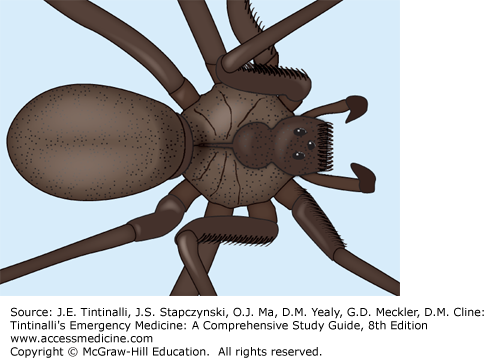

Loxosceles are brown spiders that have a worldwide distribution. Native species exist in the United States (Figure 211-1), and of these, Loxosceles reclusa (the brown recluse spider) occupies the largest geographic area and accounts for the majority of significant envenomations. In South America, particularly Brazil, Loxosceles laeta and Loxosceles intermedia account for most significant envenomations. Envenomation outside of endemic areas is unusual.18 Loxosceles spiders are nocturnal; are shy; are found both indoors and outdoors in dark, dry areas such as basements, closets, and woodpiles; and may bite when threatened. A pigmented, violin-shaped pattern on the cephalothorax of the brown recluse is often present (Figure 211-2). However, this characteristic is considered unreliable and often misinterpreted. Loxosceles species are most accurately identified by their eye pattern, which consists of six paired eyes (one anterior pair and two lateral pairs).18 Most other U.S. spiders have eight eyes arranged in two rows of four. The venom of the brown recluse contains multiple enzymes, including hyaluronidase and sphingomyelinase D, which is the major enzyme responsible for necrosis. Significant necrotic wounds are rare but possible through neutrophil activation, platelet aggregation, and thrombosis. Although both local and systemic complications of Loxosceles envenomation have been well described, the perceived threat of the brown recluse far exceeds its actual danger. For more information about recluse spiders see http://spiders.ucr.edu.

Bites by Loxosceles spiders are described as initially painless, which often prohibits possible identification of the spider. The most common manifestation of a bite is a mild erythematous lesion that may become firm and heal with little or no scar within several days or weeks. Occasionally, a more severe local reaction occurs, beginning with mild to severe pain several hours after the bite, accompanied by localized erythema, pruritus, and swelling. A hemorrhagic blister then forms, surrounded by vasoconstriction-induced blanched skin (Figure 211-3). By day 3 or 4, the hemorrhagic area may become ecchymotic, which leads to the “red, white, and blue” (erythema, blanching, and ecchymosis) sign. The ecchymotic area may become necrotic, with eschar formation by the end of the first week. The necrotic, slowly healing ulcers may not reach maximum size for many weeks after envenomation and can occasionally result in a significant cosmetic defect requiring skin grafting.

FIGURE 211-3.

Early brown recluse spider bite (approximately 8 hours old) with a violaceous center surrounded by a faint spreading erythema. [Photograph by Lawrence B. Stack, MD. Reproduced with permission from Knoop KJ, Stack LB, Storrow AB, Thurman RJ: The Atlas of Emergency Medicine, 3rd ed, © 2009 by McGraw-Hill, Inc., New York.]

Although significant systemic effects are not uncommon after bites of L. laeta, the predominant South American species, they rarely occur after bites of the brown recluse, the predominant U.S. species. Systemic effects, the hallmark of which is hemolysis, are seen more often in children and typically occur 24 to 72 hours after the bite. Other effects include nausea, vomiting, fever, chills, arthralgias, thrombocytopenia, rhabdomyolysis, hemoglobinuria, and renal failure. Disseminated intravascular coagulation and death are extremely rare.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree