BEHAVIORAL AND PSYCHIATRIC EMERGENCIES

EMILY R. KATZ, MD, LAURA L. CHAPMAN, MD, ERON Y. FRIEDLAENDER, MD, MPH, JOEL A. FEIN, MD, MPH, AND THOMAS H. CHUN, MD, MPH

The emergency department (ED) is frequently the setting for the initial evaluation of emotional and psychiatric difficulties of children and their families. As such, ED physicians must be proficient in psychiatric evaluation, crisis intervention, and disposition planning, regardless of whether a mental health professional is consulted. Even when a consultant is involved, the ED physician still shares responsibility for the patient’s care and disposition. As in any other situation involving a consultant, it is critical that the ED physician and the consultant agree on a treatment plan, both from a patient care perspective and from a medicolegal standpoint.

GOALS OF EMERGENCY MENTAL HEALTH ASSESSMENT AND CRISIS INTERVENTION

First and foremost, the assessment and management of psychiatric emergencies requires that the ED establish and maintain a safe environment for the patient, family members, and staff. Systems/protocols must be in place to enable early identification of patients at high risk of violence toward self and/or others, to provide adequate observation, to immediately intervene for unsafe behaviors, and to prevent further harm. ED physicians must be facile in evaluating for underlying causes of emotional/behavioral disturbances, including potential medical etiologies for the patient’s symptoms, assessing the risk for further decompensation and future harm, and developing adequate disposition and aftercare plans. Additional goals include providing support and stabilization for the patient’s family and offering adequate guidance around prevention/management of any future unsafe behaviors, means restriction, and indications for return to care.

KEY POINTS

ED physicians must be competent at assessing and managing psychiatric emergencies and have systems in place to safely manage acutely suicidal or aggressive patients.

ED physicians must be competent at assessing and managing psychiatric emergencies and have systems in place to safely manage acutely suicidal or aggressive patients.

All patients with mental health complaints should receive a medical evaluation to identify significant underlying or comorbid illnesses.

All patients with mental health complaints should receive a medical evaluation to identify significant underlying or comorbid illnesses.

Verbal de-escalation and trauma-informed care are key components to managing agitation. Specific techniques are available to help limit the distress of children with autism and other developmental disabilities.

Verbal de-escalation and trauma-informed care are key components to managing agitation. Specific techniques are available to help limit the distress of children with autism and other developmental disabilities.

All suicidal comments and acts should be taken seriously. Means restriction is an essential component of disposition planning.

All suicidal comments and acts should be taken seriously. Means restriction is an essential component of disposition planning.

ED physicians are typically best served using their usual “pretest probability threshold” for ordering testing/interventions on children with suspected somatization/conversion disorder.

ED physicians are typically best served using their usual “pretest probability threshold” for ordering testing/interventions on children with suspected somatization/conversion disorder.

REQUIREMENTS OF THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT

The ability to respond effectively to psychiatric emergencies of children and families requires special capacities of the ED and its staff. Ensuring safety includes not only the physical characteristics of the patient room but also the access to medical and hospital security personnel, as well as appropriate safety procedures and policies.

It is vitally important to ensure patients do not bring weapons or other dangerous objects into the ED. Procedures to achieve this end may include use of metal detectors or a physical search of the patient and their belongings. Some EDs use a protocol whereby all patients must wear a hospital gown and slippers while in the ED. This separates the patient from their belongings and can facilitate a search for harmful objects. Such a policy may also theoretically reduce the risk of patient elopement.

A safe and adequate physical space is an absolute requirement of the ED. Patients with high risk of harm to self/others need to be under constant supervision by either ED medical or security staff via direct visualization of the patient or by continuous video monitoring. At a minimum, the patient room should be free of objects that could cause harm including objects used for strangulation (e.g., medical tubing, electrical or equipment cords). Such objects should be either inaccessible to the patient (e.g., in locked cabinets) or physically removed from the room.

The optimal setting for a psychiatric evaluation is a quiet and low-stimulus environment in which interruptions are infrequent, and privacy and confidentiality are assured; ideally this environment would be a separate, distinct area from the main ED with direct access to medical and security staff and capacity for using restraints.

Clinicians in the ED should have a pre-existing relationship with a mental health team that is committed to providing child psychiatric consultation at all times. The ED should also have relationships with (a) psychiatric inpatient unit(s), for efficient transfers and hospitalizations when needed. The staff should be thoroughly familiar with the procedures for psychiatric hospitalization, including the specific legal requirements for involuntary commitment. The hospital should have specific guidelines or protocols for the management of psychiatric patients requiring admission for treatment of medical conditions.

Finally, the ED should have relationships with other social agencies and an awareness of relevant laws. The police should be aware of which children to bring to the ED for psychiatric assessment and should be prepared to remain in the ED until adequate security has been arranged. Relationships should be developed with community mental health resources, temporary shelters, and other crisis intervention centers, ensuring effective referrals when necessary. Staff should be aware of child protection laws and the procedures for emergency intervention in situations of abuse and neglect.

EVALUATION

The evaluation of the psychiatric patient should include a medical history, physical examination including a detailed neurologic examination, mental status examination, and an interview of family members.

Medical History and Physical Examination

“Medical clearance” of psychiatric patients is one of the prime reasons children with psychiatric emergencies are referred to EDs. As with all ED patients, unstable medical conditions or acute injuries are identified and treated first. Most psychiatric facilities do not have the capacity to care for acute medical problems; thus they must be stabilized prior to transfer to the psychiatric facility. The second aim is to consider possible medical causes for psychiatric symptoms. Many medical conditions, as well as acute intoxications, can mimic psychiatric disorders (Table 134.1). Failing to diagnose an underlying medical condition may result in significant morbidity to the patient. It is important to note that psychiatrically ill children may also have concomitant medical problems and, in fact, are at greater risk for presenting with emergent medical conditions such as injuries and ingestions than are nonpsychiatrically ill children.

TABLE 134.1

MEDICAL CONDITIONS THAT MAY MANIFEST WITH NEUROPSYCHIATRIC SYMPTOMS

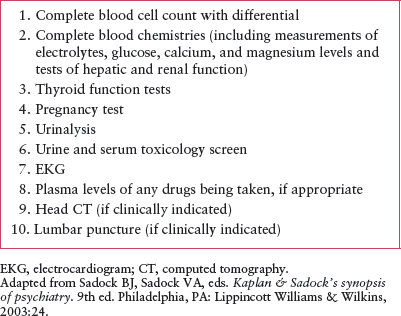

TABLE 134.2

SCREENING TESTS FOR MEDICAL ILLNESS

A thorough medical history, including current medication and possible ingestions, followed by a complete physical examination, including a complete neurologic examination is all that is required on the majority of patients. There is no “standard” set of laboratory evaluations that must be obtained to “clear” a psychiatric patient. Patients with new onset of or acute change in psychiatric symptoms, especially psychosis or alterations in mental status, must be carefully evaluated for possible underlying medical conditions. These patients may require additional laboratory evaluation or subspecialist consultation. In addition, some psychiatric facilities may request or require baseline laboratory data before accepting a transfer.

Toxicologic screens and pregnancy tests in postpubertal teens are the most frequently obtained laboratory tests. Table 134.2 lists laboratory evaluations that may be considered for psychiatric patients.

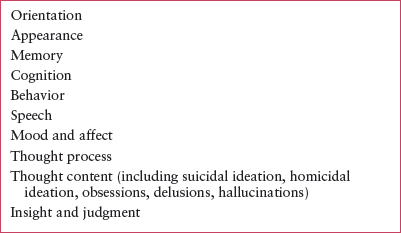

Mental Status of the Child

Evaluation of the child’s mental status takes place throughout the entire ED visit. The mental status examination provides a psychological profile of the child and contributes to the assessment of psychiatric diagnoses. Frequently much of the relevant data often emerges during the history, physical examination, and interactions with the child and family members. The emergency physician should have a systematic and thorough understanding of the mental status examination and should follow up any areas of concern with more specific questions. Table 134.3 lists the major categories of the mental status examination, with a focus on the aspects most relevant to emergency psychiatric assessment.

Family Evaluation

The mental status of the family can be assessed while observing the presentation of the history and the interactions of caregivers with the patient during the emergency department visit. The presentation of caregivers should be coherent and logical and should follow a temporal sequence. Family members under the influence of drugs or alcohol may not be fully alert and oriented. Depressed parents may appear withdrawn and downcast and may be so preoccupied with their depression that they do not focus effectively on the child’s problem or may blame the child for their own problems. Families that do not present with organized mental and social functioning may have serious difficulties resolving crises (Table 134.4).

TABLE 134.3

CHILDHOOD/ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRIC EMERGENCIES: CHILD MENTAL STATUS EXAMINATION

The goal of a family evaluation for childhood psychiatric emergencies is to determine the methods they use to help the child when distressed, how well these work, and gauge the willingness to try new strategies to help with the current crisis. When the physician approaches parents as partners, the likelihood of an effective collaboration between parents and medical staff is maximized.

Using Social Support

Some families come to the ED feeling isolated, overwhelmed, and exhausted. Often, such families have not used all the family and community resources available to them. Effective crisis intervention for psychiatric emergencies involves not only emergency treatment but also effective disposition planning for the family. The ED staff should determine what other family members and community resources are available to the family.

TABLE 134.4

CHILDHOOD/ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRIC EMERGENCIES: FAMILY ASSESSMENT

GOALS OF TREATMENT FOR AGITATED OR VIOLENT BEHAVIOR

The goals of treatment for a patient presenting with agitated or violent behavior includes de-escalation of active unsafe behavior, avoiding unnecessary physical or chemical restraints, assuring a secure setting, a process for observation of signs of increasing agitation, and establishing a safe, appropriate disposition plan that includes guidance on means restriction.

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

Pediatric emergency providers are called upon to assess potentially violent individuals. EDs may also find themselves on the front lines of violence or possibly active shooter scenarios, and thus need adequate screening and response policies in place to manage acute safety.

Remember that agitated or violent behavior may be situation dependent; once removed from the situation, the patient’s behavior may significantly improve. In fact, the behavior may appear to be normal by the time they arrive at the ED. It is potentially a mistake to equate the lack of significant symptoms in the ED with the absence of a significant problem. The problematic behavior may easily reoccur if the patient is returned to the same situation without any appropriate intervention(s). In assessing the potentially violent patient obtain thorough collateral information, as patients themselves may not be fully forthcoming about their thought content or plans.

There are important medicolegal considerations in caring for these patients. The ED physician may have Tarasoff obligations to warn and protect identified targets of violence and must also consider their obligations to protect society at large. Every state has laws regarding involuntary admission of patients at imminent risk for harm to self and/or others. It is incumbent upon ED physicians to familiarize themselves with their state’s laws and regulations.

A significant percentage of patients with psychiatric complaints have experienced trauma in the past. Treatment in the ED can be retraumatizing in numerous ways, including having their clothing and belongings removed, having a security guard present, being confined to a single room, and receiving chemical and/or physical restraints. For some patients, these factors may be the underlying or contributing cause for their agitated or aggressive behavior. Chronically traumatized children often have an elevated stress response and live in a state of constant alarm; the ED experience may be difficult for them to handle. “Trauma-informed care” assumes that all patients have trauma in their past, the clinician’s approach should allow patients to feel some control over their current situation. Creating a space where the child feels safe, giving them choices when possible, and actively listening may improve care. It helps providers maintain compassion when dealing with children that, on the surface, seem challenging or antagonistic. Implementing such care usually requires careful negotiations with patient, as well as planning and flexibility by ED clinicians.

Clinical Considerations

Clinical Recognition

Agitation may manifest in a wide variety of behaviors, depending on the patient’s age and developmental and physical state. Signs and symptoms may include restlessness, hyperactive motor activity, confusion or disorientation, uncontrollable crying, verbal threats, and overt physical violence toward oneself, others, or physical property.

Triage

A patient who is mildly agitated or who presents for evaluation of threats of harm may be able to wait safely in an ED waiting room and may benefit from de-escalating strategies. However, care should be taken to monitor these patients for signs of escalation and to prevent elopement. A thorough search of persons and belongings should be performed.

Actively/potentially violent or highly agitated patients require immediate transition to a secure area of the ED that is under the constant observation of hospital personnel. Security officers should be used whenever patients have the potential for significant violence or aggression.

Initial Assessment

Agitation or violence is a symptom of various psychological, medical, and toxicologic disturbances. The ED physician’s assessment should focus on differentiating among the many possible causes.

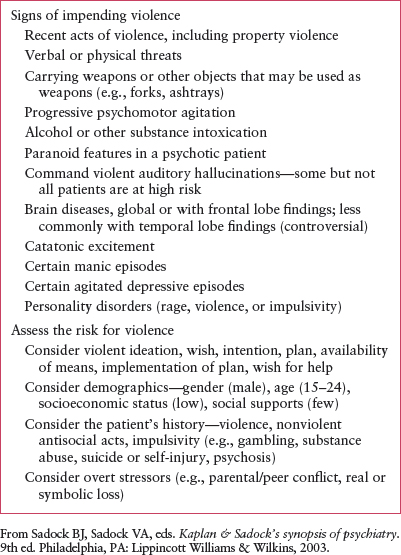

Assessment and frequent reassessment signs and symptoms for violence and danger to others are important (Tables 134.5 and 134.6). Patients should be asked if they currently have any violent or homicidal thoughts, if they have specific plans or thoughts, if they have access to firearms or other weapons. Unfortunately, no single sign, symptom, or set of criteria successfully identifies all patients with significant risks for violence.

Management

Verbal De-escalation. Studies have shown that when hospital staff are trained in verbal restraint techniques, there is significant decrease in the use of chemical and physical restraint in the care of psychiatric patients. Ideally, all ED staff participating in the care of psychiatric patients should have training in verbal de-escalation techniques (Table 134.7).

All verbal de-escalation techniques share common features. Strategies include approaching the patient with a calm, nonjudgmental manner, and being empathetic. The simple act of listening can have a powerful effect. The patient should be reassured that the ED staff is there to help and work with them. Frequent updates about the care plan can help the patient stay calm.

Patients should be given as much autonomy as possible; try to present a few reasonable treatment options and allow them to choose. Patients often feel empowered and are better able to control themselves. It is equally important to set clear limits with the patient to maintain safety. Limit setting, done in a nonpunitive manner, may include discussing acceptable and unacceptable behaviors as well as consequences for these behaviors. With few exceptions, one should avoid “bargaining” with patients as this may encourage limit testing. Feeling threatened or punished may exacerbate a patient’s agitation and/or behavior.

TABLE 134.5

ASSESSING AND PREDICTING VIOLENT BEHAVIOR

TABLE 134.6

PREDICTORS OF DANGEROUSNESS TO OTHERS

TABLE 134.7

VERBAL DE-ESCALATION/CALMING TECHNIQUES

Restraints. Physical and chemical restraint may be necessary to contain the patient’s violent behavior. However, controversy exists regarding in what situations and when restraint is indicated. While the use of restraints can prevent significant and potentially life-threatening violent outbursts and can help an out-of-control patient calm down, restraints can also be physically harmful and traumatizing to the patient, the family, and the staff.

Restraint has the potential to harm patients. Adverse reactions to chemical restraint, physical harm and death due to physical restraint, as well as psychological harm (e.g., feelings of shame and/or of being personally violated, frank symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) have all been reported. Both the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Joint Commission mandate that healthcare institutions monitor their use of restraints, and develop and maintain protocols in which patients are treated in the least restrictive manner possible. ED physicians and staff thus need to be familiar with their institution’s restraint policies, practices, and guidelines.

Medications for Agitation. Medications can be a useful tool in helping to manage unsafe behaviors in the pediatric emergency setting and can be used to treat agitation related to the patient’s underlying condition. This is distinct from the concept of chemical restraint, which CMS defines as “a medication used to control behavior or to restrict a patient’s freedom of movement and not standard treatment for the patient’s medical or psychiatric condition.” Although medications are extensively used to treat agitation and there are numerous published studies of their use in the adult ED and psychiatric settings, there is scant literature on their use in pediatric populations. In addition, as is the case with many medications and pediatric populations, few of the medications have FDA approved indications for treating agitation associated with pediatric mental health conditions, and none are approved for the purpose of chemical restraint in children and adolescents. Any medication used for chemical restraint is thus an “off-label” use of the medication. Although there are multiple published studies using the oral forms of the newer, atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents, there is scant published evidence regarding the parenteral forms of these medications. These limitations aside, it is widely held by experienced psychiatric and pediatric emergency physicians that these medications are both safe and efficacious. Adverse reactions to these medications in the acute setting are rare and usually easily managed when they arise.

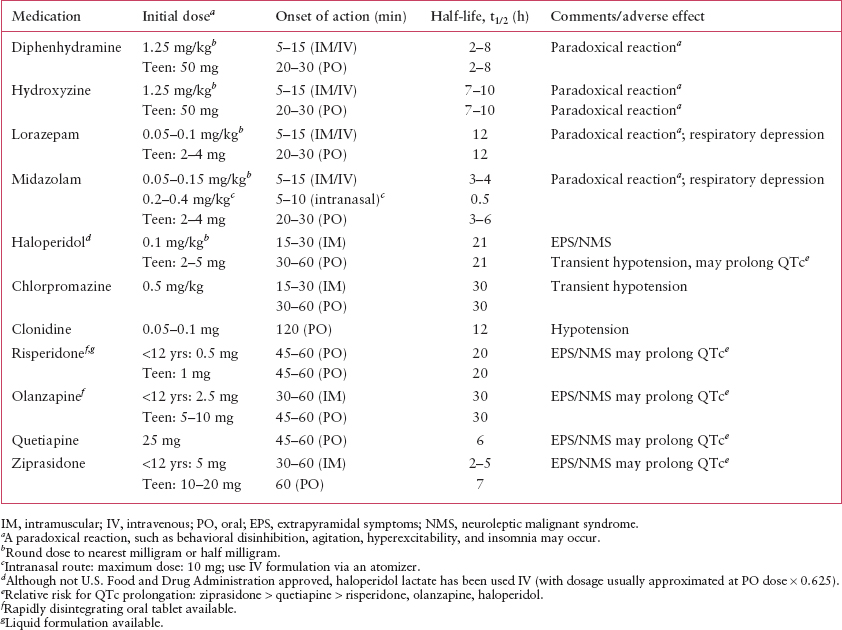

TABLE 134.8

CHEMICAL RESTRAINT MEDICATIONS

Medications that are commonly used for agitation and the appropriate initial dose of these medications are listed in Table 134.8. It is acceptable to round the dose to the nearest half or whole milligram or the nearest whole pill dose. Alternatively, for patients already on psychiatric medications, their current dose or an increased dose of one of their medications may be appropriate.

The choice of medication(s) should be based on the level of the patient’s agitation or dangerousness. For mild agitation, antihistamines, alpha-adrenergic agents such as clonidine, or benzodiazepines are the first line of treatment. For moderate to severe agitation, possible medications include benzodiazepines, alpha-adrenergic agents, typical antipsychotics, and atypical antipsychotics. The ED physician should choose between these different agents on the basis of the degree of agitation, the patient’s willingness to take oral medications, and the medication side effect profile. The newer, atypical antipsychotics may have fewer adverse effects than traditional antipsychotics (e.g., extrapyramidal symptoms [EPS], dystonic reactions, neuroleptic malignant syndrome [NMS]). However, their use in the ED may be limited in that ziprasidone, aripiprazole, and olanzapine are the only atypical antipsychotics that have an immediate release parenteral form, and there is limited experience using these medications in pediatric populations. The rapidly dissolving oral forms of olanzapine, aripiprazole, and risperidone may be an acceptable alternative to physicians and patients.

For patients with severe agitation, rapid tranquilization is the strategy favored by many experts. In this approach, a dose of a benzodiazepine and an antipsychotic are given simultaneously. These medications can be given orally but often will need to be given parenterally. If needed, subsequent doses can be given 60 and 120 minutes after the initial dose. This approach may be more effective than a single agent alone and may result in the use of less total medication. A variation of this approach is to alternate medications, that is, give a dose of one medication and reassess the patient 30 minutes later. If the patient’s agitation has not sufficiently resolved, a dose of the other medication is given. The patient is reassessed every 30 minutes and redosed with the appropriate medication as needed.

Both haloperidol and the atypical antipsychotics, ziprasidone to the largest degree, may cause QTc prolongation. As such, patients receiving these medications should be closely monitored. There is no consensus regarding the prophylactic use of benztropine (1 mg oral (PO)/intramuscular [IM]) or other anticholinergic agents in patients receiving antipsychotics. Some experts favor giving such medications to all patients receiving antipsychotics, for the prevention of EPS. Others prefer to use these medications only if and when EPS develop.

NMS is a rare complication of antipsychotic use. It is more commonly seen in young, muscular males, although it may occur in patients of any age, gender, and body habitus. Pre-existing dehydration and chronic antipsychotic use are other risk factors for developing NMS. Because there is no test that absolutely confirms it, NMS can be vexing to diagnose. In addition, the clinical picture of fever, altered mental status, and autonomic hyperactivity may be difficult to differentiate from meningoencephalitis, intracranial injury, various toxins, serotonin syndrome, or an underlying psychiatric condition. It should be strongly considered in any agitated patient whose condition worsens or does not resolve when given antipsychotic medication.

Of note, two antipsychotics, thioridazine and droperidol, currently carry FDA “black box” warnings as they may cause fatal arrhythmias.

Physical restraint. Any device that restricts a patient’s mobility is a physical restraint. Theoretically, a bed rail is a form of restraint. In the treatment of agitated patients, however, physical restraints specifically refer to devices used with the express purpose of restraining a patient’s limbs. Only such approved devices should be used for physical restraint.

The Joint Commission analyzed cases of physical restraint and identified several risk factors associated with patient deaths. Asphyxiation was associated with excess weight being placed on the back of prone patients, a towel or sheet being placed over the patient’s head to protect against spitting or biting, and airway obstruction due to placing the patient’s arm across the neck area.

A minimum of five trained staff are needed to restrain a patient, one to control each limb and one for the patient’s head. For extremely violent or agitated patients, the prone position, although more restrictive, is safer for both the patient and the care provider. Physically restrained patients need constant observation by medically trained. The Joint Commission mandates documentation of patient’s vital signs, assessment of behavioral status, and offering of food, water, and access to bathroom facilities at regular intervals. These standards also mandate a face-to-face evaluation of the patient by the ordering physician within 1 hour of the patient being placed in restraints. Orders for restraint can be renewed, but each order cannot exceed 1 hour for children younger than 9 years, 2 hours for children and adolescents between 9 and 17 years, or 4 hours for adults.

Restraints should be removed as soon as possible in an organized manner, taking into account the severity of the patient’s agitation. The same number of personnel needed to place the restraints should be present when the restraints are removed, in case the restraints need to be reapplied. There is no consensus as to the optimal method; some remove all restraints once the patient is judged to be safe. Others prefer a stepwise approach, releasing an arm first, then the opposite leg, and finally the remaining limbs. Between each step, the patient is informed that if they remain under control, the removal process will continue. Patients should not be left with only one limb restrained. They have too much mobility and could injure themselves or others if they become combative.

Disposition

Patients who are at imminent risk of serious harm to others and who cannot be safely maintained in lower levels of care require admission to an inpatient psychiatric facility. Alternatives to inpatient admission include partial-hospitalization programs, acute residential treatment, in-home services, routine outpatient care, and, in rare circumstances, placement in the juvenile justice system. Outpatient and in-home services may be of particular use when family issues are playing a significant role in the unsafe behaviors. Brief placements in respite care or alternative placements for those in foster care may also be considered as a diversion from inpatient hospitalization. Special efforts should be made to avoid inpatient hospitalization in very young children, children with reactive-attachment disorders, or those with personality disorders; for these populations in particular, admission may be countertherapeutic.

Caregivers of those being discharged home should be counseled regarding means restriction of potential weapons, provided with de-escalation strategies, and instructed on indications for return. ED physicians may also use this opportunity to help parents establish, present, and/or reinforce any pertinent behavioral rules, rewards, consequences, etc. for the child.

In the event that an ED physician is evaluating and managing a truly homicidal patient, the ED physician has a duty to both warn the potential victim (typically via contacting local police) and to take actions to protect the potential victim from harm (e.g., by psychiatrically hospitalizing the patient). This duty was established in the landmark case of Tarasoff versus the University of California and has withstood numerous court challenges. This duty to warn and protect the potential victim supersedes the physician’s duty to maintain patient confidentiality.

SUICIDE ATTEMPTS

Goals of Emergency Evaluation and Treatment

The goal of emergency evaluation and treatment of patients presenting in the wake of a suicide attempt are to identify and treat any potential medical sequelae of the attempt, to maintain the patient’s safety in the ED, and to establish an adequate disposition plan.

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

Suicide is the final common pathway for various situations in which the child experiences a pervasive sense of helplessness, with a perceived absence of alternative solutions. To the distressed child, suicide appears to be the only solution to his or her problems and the family’s problems. Most suicide attempts occur in depressed children; others occur with children experiencing major losses, such as serious illness or death in the family or in children with depression with associated impulsivity. A small but significant percentage of suicide attempts occur in psychotic children and adolescents (Table 134.9).

Children have differing conceptions of death at various ages. Up to age 5, death is seen as a reversible process in which the activities of life still occur. From 5 to 9 years, the irreversibility of death is beginning to be understood, but death is personified rather than seen as an independent event. It is not until about age 9 that death is seen as irreversible in the adult sense of being both final and inevitable. Even then, however, the child may imagine his or her own death as being reversible. Under such circumstances, a suicide attempt may have a different meaning than for an adult, where suicide corresponds to a definite end of one’s life.

While it is common for psychiatric symptoms to be present for weeks to months before an attempt and the vast majority of patients who suicide meet criteria for a psychiatric or substance abuse diagnosis at the time of their death, the time between a patient deciding to kill themselves and carrying out the act is often quite short and often occurs in the midst of an acute crisis. Studies of survivors of potentially lethal attempts suggest that close to 25% act on their decision within 5 minutes, another nearly 25% act between 5 and 19 minutes, while another nearly 25% act between 20 minutes and 1 hour. This means that effective prevention efforts include the strategies of identifying and treating psychiatric disorders prior to the development of suicidal ideation as well as efforts to restrict access to the most lethal and common means of suicide attempts.

Emergency physicians must provide clear guidance around means restriction including firearms and potentially dangerous medications. Over 80% of pediatric patients who suicided by firearm use a family member’s firearm. Of those, over two-thirds used guns that were unlocked and the remainder either knew how to open the gun safe or were able to break in. In one study, nearly a quarter of children whose parents believed they had never handled their firearms were mistaken. Removal of firearms (and potentially dangerous medications) from the home—at least temporarily—is ideal; safe storage is a minimum.

The dichotomy sometimes drawn between suicide “attempts” and suicide “gestures” is ill conceived, and the lethality of attempt does not always correlate with lethality of intent. As a corollary, minimizing a suicidal act as “just cry for help” by not responding adequately only invites a potentially far-more-lethal “scream for help.”

Suicidal ideation is common enough that EDs could consider screening all teens for suicidal ideations or attempts, especially ones engaging in any high-risk behaviors or with other identifiable risk factors. Several screening tools, such as the Risk of Suicide Questionnaire (RSQ) and briefer 2- and 4-question screening tools are effective and accurate in screening for suicidality in patients presenting with nonpsychiatric complaints.

TABLE 134.9

POTENTIAL SOURCES OF ADOLESCENT SUICIDE ATTEMPTS

Clinical Considerations

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree