CHAPTER 15

Atlanto-Axial Joint Injections

INTRODUCTION

The atlanto-occipital (AO) and atlanto-axial (AA) joints are unique joints in the spine, connecting the cervical region to the base of the skull. The AA and AO joints are an often under-appreciated cause of pain and should be part of the differential diagnosis of cervical spine pain and occipital headaches.

INDICATIONS

AA joint injections are indicated for:

• The diagnosis and treatment of AA joint pathology, which presents as deep pain in the suboccipital region, often unilateral.

![]() Especially after flexion/extension injuries

Especially after flexion/extension injuries

![]() Particularly when movement in rotation causes pain

Particularly when movement in rotation causes pain

• Cervicogenic headaches that are impairing functional life indices (poor restorative sleep capacity, endurance, and quality of life).

• Persistent upper cervical pain that is leading to escalating opioids to control symptoms.

• Persistent occipital neuralgia poorly responsive to occipital nerve blocks.

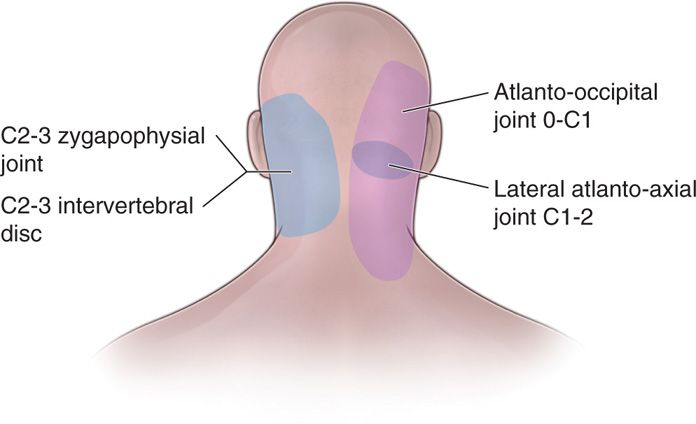

The lateral AA joint is a common cause of cervicogenic headache and may account for up to 16% of patients with occipital headache.1 The AA joint primarily refers to the occipito-cervical region, radiating to the posterior auricular region.2 There may be decreased range of motion, crepitance, and abnormal head position. When pain is increased at far cervical rotation, either during protraction or retraction, the AA joint is likely to be responsible. Unfortunately, the radiologic diagnosis of AA joint pathology has a high false-negative result, since onset of pain precedes any observable structural abnormalities. Characteristic referred pain patterns from AA and AO joint pathology overlap those patterns from the greater and lesser occipital nerves as well as the pain from the C2/C3 facet joint,2 making clinical diagnosis difficult.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

• Infection at the injection site

• Coagulopathy

• Cervical spine instability

• Previous cervical fusion at that level

RELEVANT ANATOMY

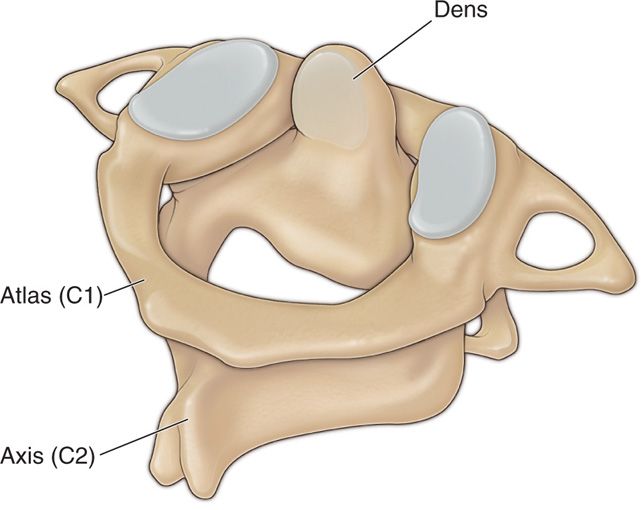

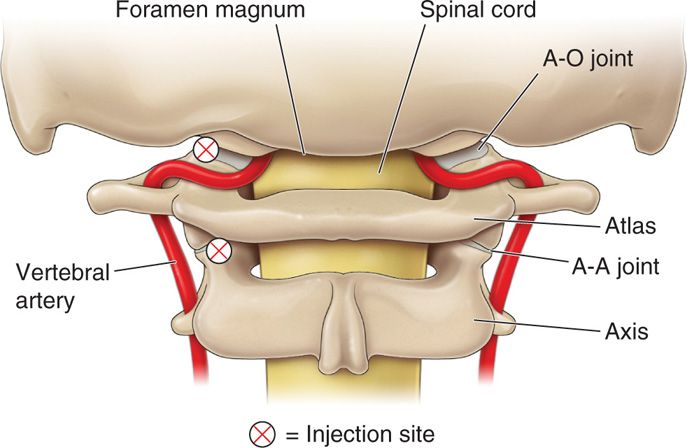

• The first two bones of the cervical spine are unique in their shape and function. The C1, or atlas, vertebra is unique in that it does not have a ventral vertebral body, but rather functions as a relay between the occiput and C2 (Figure 15-1).

• The AA joint articulates the atlas (C1) with the axis (C2) and constitutes the C1-C2 joint.

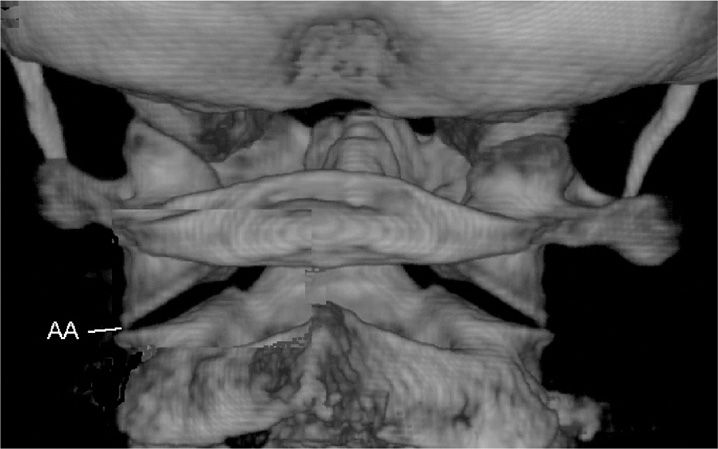

• The AA joint slopes caudally and laterally (Figures 15-2 and 15-3).

• Unlike the lower cervical segments, the AO and AA joints lack intervertebral discs and uncinate processes.

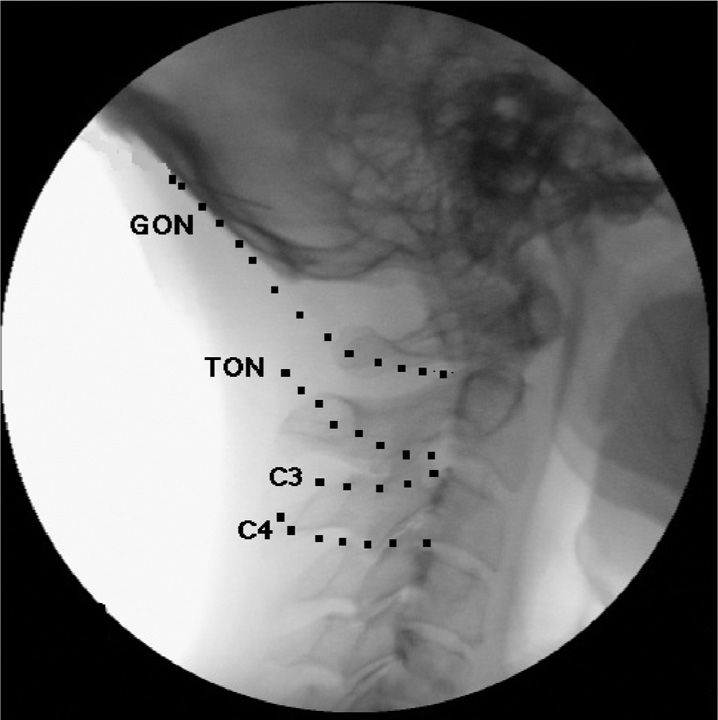

• The C1 and C2 nerves, which are primarily sensory, travel through the suboccipital muscles to the occipital area as the greater occipital nerve and the lesser occipital nerve (Figure 15-4).

• The dorsal root ganglion of C2 lies at the medial portion of the AA joint.

• The posterior arch of C2 is very deep to the skin and difficult to palpate.

• The transverse processes are long and perforated by a foramen, which protects the vertebral artery, and the anterior and posterior arches form a triangular conduit for the brainstem.

• There are grooves in the C1 posterior surface that accommodate the vertebral arteries. The vertebral artery transverses a variable pattern through the wide opening within the transverse process of C2 and travels across the body of C1, runs on the lateral one-third of the AA joint dorsally, to enter the foramen magnum medial to the AO joint (Figure 15-5).

Figure 15-1. Lateral view of AA and AO joints.

Figure 15-2. AP drawing of AA and AO joints.

Figure 15-3. CT reconstruction image of AA joints.

Figure 15-4. Greater, lesser, and third occipital nerve path.

Figure 15-5. Vertebral artery and relationship to AA and AO injection sites.

The AA joint shares similar innervation with the AO joint, and is responsible for paracervical myofascial pain, bony joint pain, and intraarticular pain in a variably represented referred pain pattern. The AA joint holds 0.7 cc.3

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

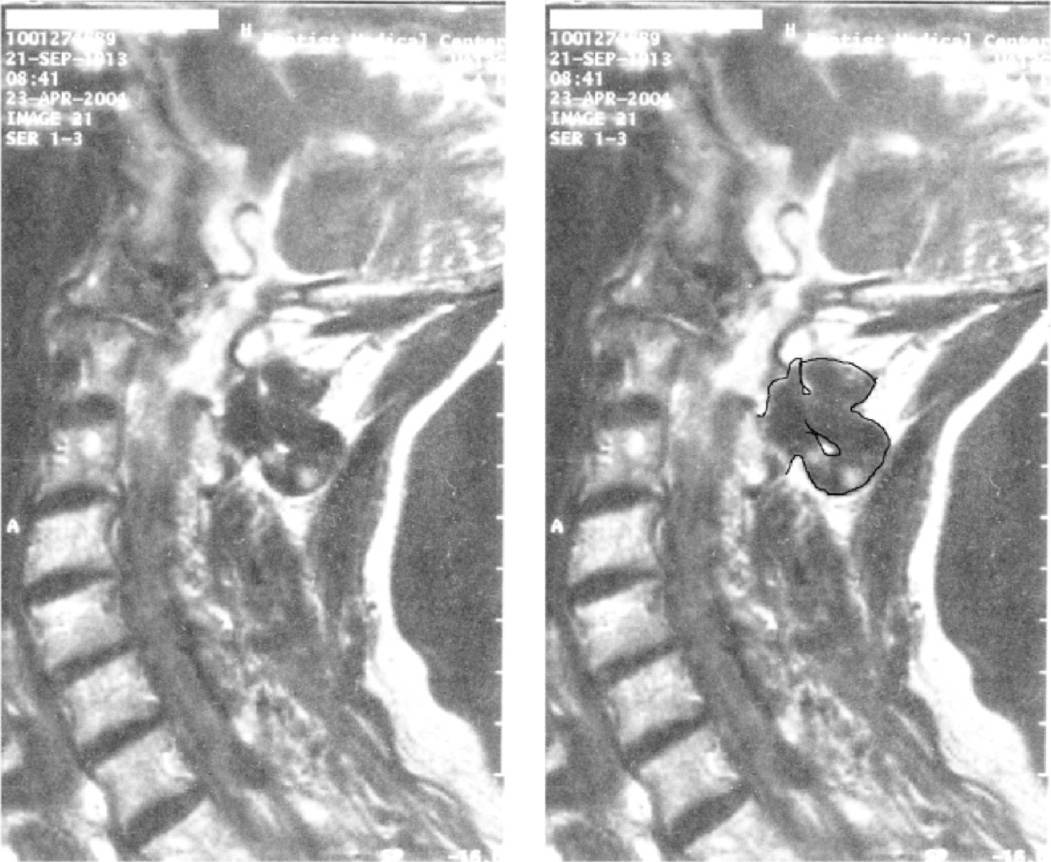

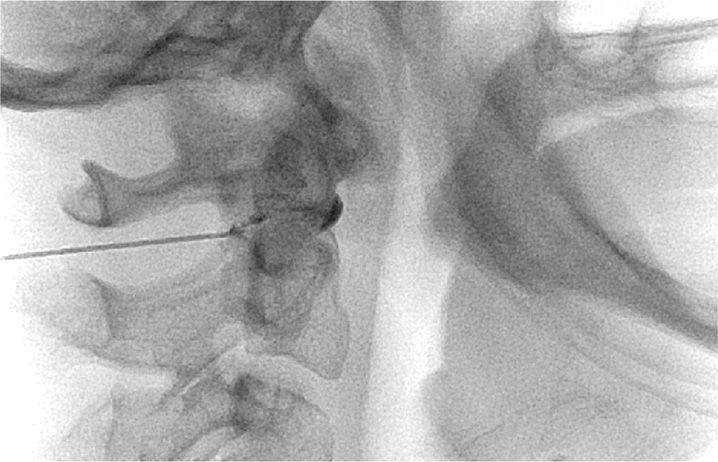

A torturous and unpredictable anatomical variance between the vertebral artery and the bony structures (Figure 15-6) suggests that no reliable placement of needle may be expected to be completely safe, and trans-arterial or intra-arterial injections are always a potential disastrous complication; therefore, IV access is mandated. If the patient is anticoagulated, these medications should be stopped. The risk-reward ratio should be in the patient’s favor whenever assessing when anticoagulation therapy should cease. This requires communication with the patient’s primary care practitioner to further define the risk of bleeding versus the risk of cardiovascular event.

Figure 15-6. Tortuous vertebral artery.

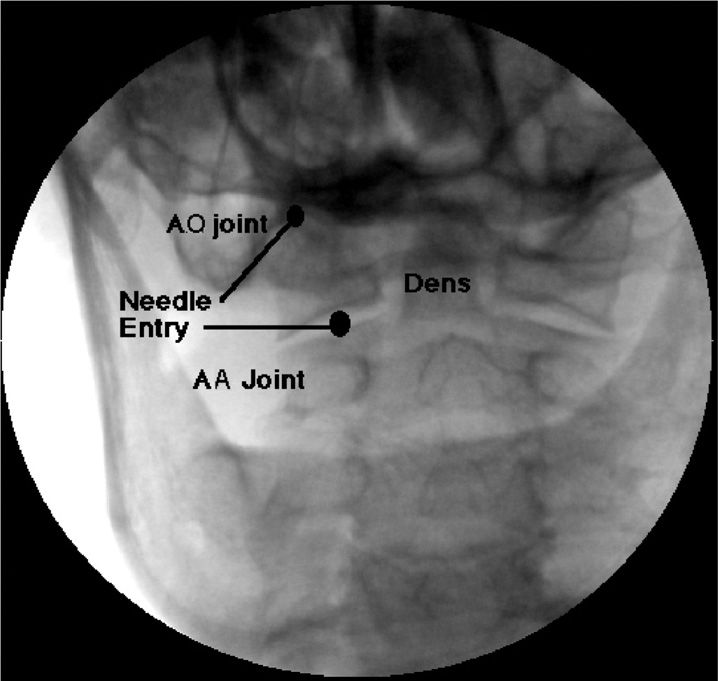

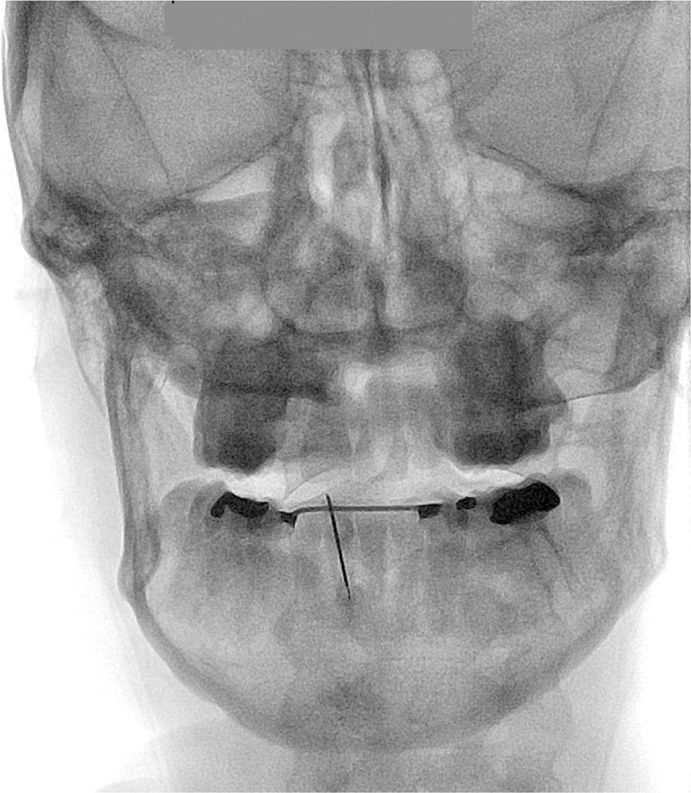

Fluoroscopic Views

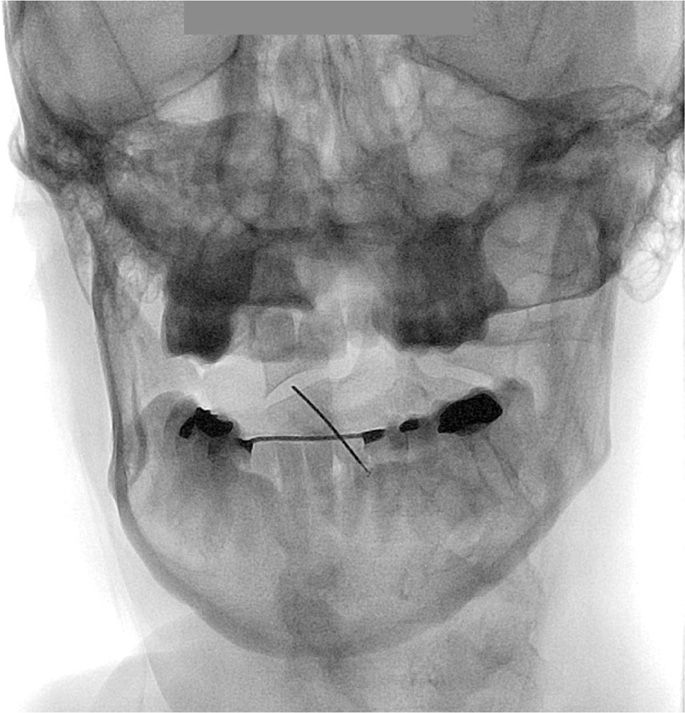

The fluoroscope is positioned in order to visualize the AA joint as a crisp line. An “open mouth” view may be necessary to adequately visualize the joint (Figure 15-7).

Figure 15-7. Open mouth view of AA joint.

Positioning of Patient

The patient is placed in the prone position with the neck slightly flexed and the chest on a pillow, or in the lateral position with the head flexed and rotated 45 degree for the lateral approach.

Selection of Needles, Medications, and Equipment

Needles

![]() 22-gauge 3.5″ Quinke needle or blunt tipped needle with introducer

22-gauge 3.5″ Quinke needle or blunt tipped needle with introducer

![]() Extension tubing

Extension tubing

![]() 3-cc syringes (Luer locked)

3-cc syringes (Luer locked)

Medications

![]() Nonionic contrast

Nonionic contrast

![]() Nonparticulate steroid

Nonparticulate steroid

![]() Local anesthetic (lidocaine, bupivicaine)

Local anesthetic (lidocaine, bupivicaine)

Equipment

![]() C-arm

C-arm

INTRAOPERATIVE TECHNICAL STEPS

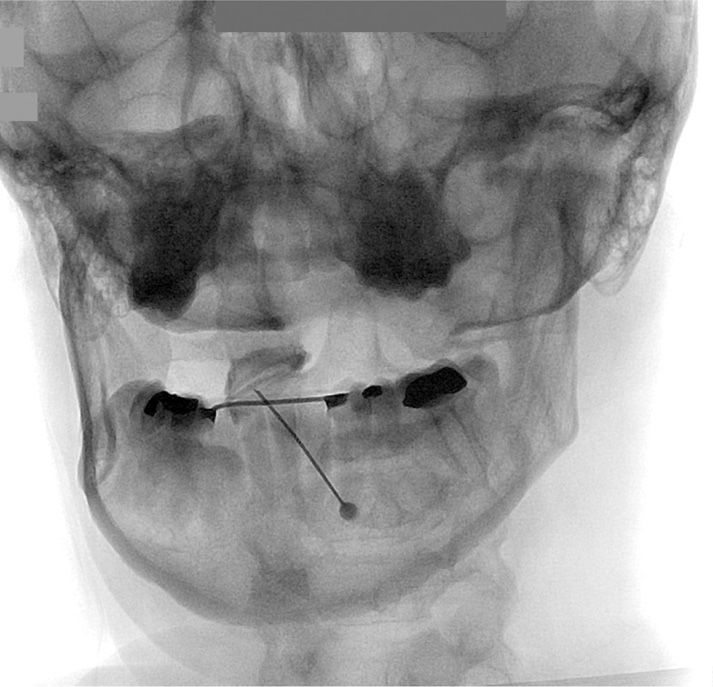

• After a sterile prep and drape, subcutaneous local anesthetic is injected. A 22-gauge subarachnoid needle (thinner needles are too flexible) is advanced under fluoroscopic control using a “gun barrel” technique to guide the needle to the inferior medial aspect of the AA joint (Figure 15-8).

• Once needle contact is made on the inferior edge of the joint line, the needle slides (not losing contact with the periosteum) just off the edge of bone into the joint capsule (Figure 15-9).

• A distinctive “pop” is often felt as the AA joint is entered.

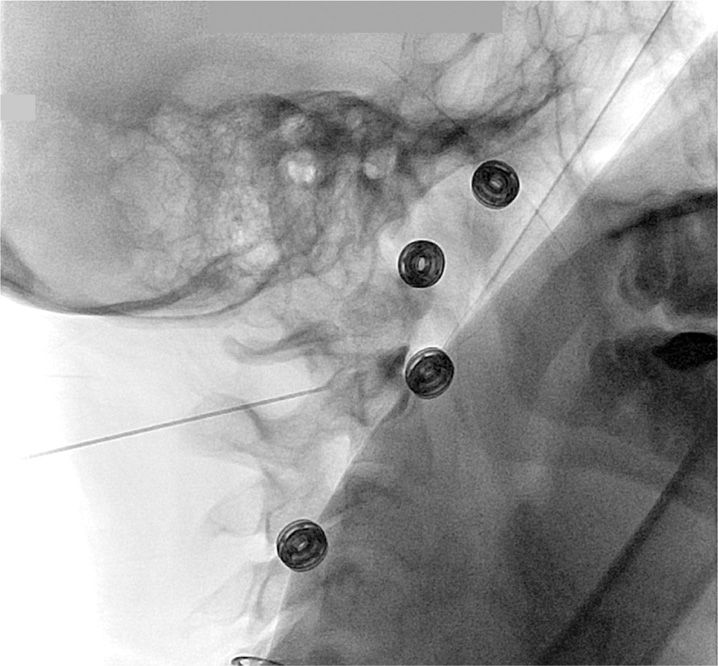

• The C-arm is then rotated into a lateral view for confirmation that the needle has entered the joint space (Figure 15-10).

• About ¼ to ½ cc of nonionic contrast is then injected, utilizing extension tubing to decrease needle movement. Contrast should spread throughout the joint capsule (Figures 15-11 to 15-13).

• Venous runoff of the contrast almost always means that the needle is outside the joint, which has a rich vascular plexus (primarily venous).

Figure 15-8. Placement of needle on inferior AA joint.

Figure 15-9. Advancement of needle into AA joint.

Figure 15-10. Lateral view of AA joint needle placement.

Figure 15-11. Lateral view of AA joint injection of contrast.

Figure 15-12. AP view of AA joint injection of contrast.

Figure 15-13. CT 3D reconstruction of AA joint injection.

![]() If there is runoff, or spread the contrast into the epidural space, the injection should be terminated.

If there is runoff, or spread the contrast into the epidural space, the injection should be terminated.

• After confirmation of location and negative aspiration, a total of 0.5 cc of local anesthetic and steroid is injected.

![]() Because of the proximity to vascular structures, concerns regarding intravascular injections of particulate steroid, prudence may suggest the use of a non-particulate steroid.

Because of the proximity to vascular structures, concerns regarding intravascular injections of particulate steroid, prudence may suggest the use of a non-particulate steroid.

POSTPROCEDURE CONSIDERATIONS

Because there may be a loss of proprioception at the base of the skull with this injection, dizziness and ataxia as well as a sensation of upper neck “weakness” are not unexpected.

Monitoring of Potential Complications

• The most dreaded complication of the AA joint injection is an intravascular injection into the adjacent venous plexus, vertebral artery, or carotid artery, with the resultant risk of seizures.

• It is therefore recommended that only a small amount of local anesthetic be injected to decrease the potential for cardiovascular or central nervous system toxicity. Anatomically, these joints may share a connection to the epidural space, and careful evaluation of epidural extravasation is necessary prior to injection of local anesthetic to avoid a high epidural or spinal anesthesia.

• Other complications include infections, post dural puncture headache, spinal cord injury, and ataxia.

Clinical Pearls and Pitfalls

• Although a 25-gauge needle has been described, I am concerned that it is too flexible, and would more likely deflect in an undesirable direction.

• The AO and AA joints are often evaluated and treated together.

• Although differential local anesthetic blocks are often recommended in other areas of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine because of the difficulty in performing the AA and AO injections, it probably is not necessary or appropriate to use “double local anesthetic” techniques.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree