Chapter 7

Assessing pain

At the end of this chapter readers will be able to:

1 Understand the differences between pain assessment and pain measurement.

2 Describe the types of pain evaluation commonly used.

3 Describe some of the most commonly used pain measurement tools.

4 Be aware of some consensus guidelines around pain assessment.

5 Understand the impact which culture, ethnicity, religion and gender can have on pain assessment.

OVERVIEW

Specific tools for measuring aspects of pain will be described. For each measure, utility, reliability and validity will be addressed. In conjunction with undertaking pain measurement for treatment, outcome measurement for determining therapy efficacy will also be reviewed. Lastly, we will consider other factors that may influence outcomes in the assessment and measurement of pain. Key terms are defined in Box 7.1

SOME IMPORTANT ISSUES IN THE MEASUREMENT OF PAIN

Assessment of an individual’s pain is an important task for health professionals, yet pain is a subjective phenomenon that defies objective measurement (Unruh et al 2001). The perception, interpretation and assessment of a patient’s pain are restricted, in theoretical, philosophical, diagnostic and practical terms, by the subjective nature of the pain experience. There have been many attempts to make a coherent objective assessment of pain (Beecher 1959; Noble et al 2005; Unruh et al 2002), including the application of numeric rating scales in clinical practice (Noble et al 1995). Most methods for assessing a person’s pain have relied on a simple scale of pain magnitude or intensity (Gracely & Kwilosz 1988). A valuable channel of information arises from the language used by the patient; that is, by how they describe it (Fernandez & Boyle 2001; Strong et al 2009).

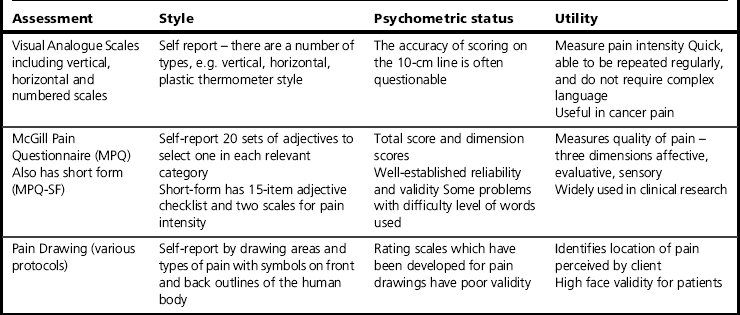

The number of measurement tools available to assess and measure a person’s pain has continued to increase over the past decade. Indeed, there is a plethora of literature about the measurement of pain experience. How does one decide what measures are suitable for a particular setting? There are three important considerations. The measure must have clinical utility. It must also be reliable, and it must be a valid measure of that aspect of pain for which it is intended. We will briefly discuss these three considerations before we discuss types of measures, and then measures for each of the four components of pain (description, temporal nature of the pain, response, impact). Additionally, we will look at the recommendations from some consensus guidelines about the necessary and sufficient dimensions and assessments of pain. Key terms are described in Table 7.1.

One other important aspect to be covered in this chapter is the impact of culture, ethnicity, religion and gender on pain assessment. As Fabrega and Tyma said, ‘It follows logically that culture and language are inextricably bound together with the communication of pain’ (Fabrega & Tyma 1976, pp 323–324). the assumption that one measurement tool, developed for a particular culture, has direct applicability to other cultures and languages will be examined.

Clinical utility

Clinical practice is often pragmatic or local in style, and may seem not to exactly match the theory on which a measure is based. Often, the primary consideration is that pain measurement must be clinically helpful to the setting in which it will be used. Voepel-Lewis et al (2010) argue that pain assessment tools are only useful when adaptable within busy settings, such as in intensive care situations. Most therapists find that there is a limit to the available time for assessment and measurement. Clinically useful measurement is therefore parsimonious; short, efficient measurements collecting the maximum useable information are preferred. For this reason, in order to be comprehensive and parsimonious, it is advisable to aim for only one measurement tool from each of the four dimensions (description of the pain, temporal nature of the pain, responses to the pain, impact of pain) unless more measurement is essential.

The use of many different outcome measures has meant that the results of different research trials have often been difficult to compare with each other and with results in clinical practice. In recent years efforts have been made to reach consensus on key pain measures to be used in research in order to improve consistency across clinical trials. The recommendations are referred to as the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT; Dworkin et al 2005; Turk et al 2008). While they represent an important step in reducing the number of measures used, it is important to bear in mind that they are focused on research rather than clinical practice. Similar consensus was reached by a different group regarding a wider range of patient-reported health-related outcome measures. The Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System framework (PROMIS, see www.nihpromis.org) includes measures such as social health and social function, as well as pain, emotions and fatigue. Although its main focus is on research, the tools are likely to be useful to clinicians as well. Finally, the EuroQoL group have attempted to put together a simple health outcome measure which consists of six key questions including pain, the EQ-5D (see www.euroqol.org).

Reliability of pain measures

Reliable measures of pain provide consistent results from one time of use to the next. To illustrate, a reliable thermometer will give the same temperature from one hour to the next in a static thermal state. If there is much fluctuation in the temperature readings in the static thermal state, then the thermometer is not reliable. Of course, if circumstances change, such as the patient develops a fever, we would expect a reliable thermometer to measure this change. This property of a measurement tool is termed its responsiveness to change (Guyatt et al 1987). A reliable measure of pain also will provide similar information from one time to the next unless the pain changes (i.e. intra-rater reliability). The measure will also give the same results, or very close to the same, if two different therapists administer the measure (i.e. inter-rater reliability).

How does the reliability of a pain measure relate to clinical usage for therapists? In selecting the most appropriate assessment or battery of assessments to use for any particular patient, the aim is to balance the need for psychometrically reliable data against the need for a measurement tool that can be administered efficiently. It may be that the most reliable measurement tool is very long and the patient has a short attention span, or requires so many other evaluations that a long one is impractical. In many clinical situations, the time available for completing an assessment is short. The measures that are used need to use time efficiently. For example, Krebs et al (2009) found that an ultrashort, three-item adaptation of the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) (Payen et al 2001) was comparably valid for assessing pain among primary care and ambulatory clinic patients in relation to the original BPI.

The utility of a measurement is also limited by its complexity. In some situations, the most effective way to assess the quality of pain would be the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) (Melzack 1975), but if the patient speaks little English or any of the languages into which the MPQ has been translated, then a visual analogue scale (VAS) may be more useful. Other special populations, such as critically ill adults and children who are unable to report on their pain, have been shown to benefit from the use of the simple Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability (FLACC) behavioural tool (Voepel-Lewis et al 2010). This same study demonstrated correlation between FLACC results and those arising from 0–10 numeric rating scale usage, a measure which Jensen et al (1999) found to have sufficient reliability and validity for use with patients with chronic pain, especially in research involving large sample sizes.

Validity of pain measures

A pain measure is valid if the measure truly measures what it is supposed to measure and not something else. Knowing exactly what some pain measures are measuring may be more contentious than one would expect. The pain drawing (Parker et al 1995), for instance, may not simply describe areas where patients feel pain of various types. Sometimes anatomically and physiologically impossible distributions of pain are selected. Does the pain drawing describe the location of pain or does it measure something else, like psychological distress? In fact, it has been proposed that scoring systems for the pain drawing may be used to assess psychological distress, but efforts to do this have met with equivocal success (Parker et al 1995). Unusual drawings may convey psychological distress but they may also mean an unusual pain distribution (Waddell 2004).

Types of pain measures

The distinction between categories of pain measures and their strengths and limitations will be assisted by completion of Reflective exercise 7.1.

Self-report

As suggested in the Reflective exercise, there are three types of pain measures: self-report measures, observational measures and physiological measures (see Box 7.2). The first type is ‘self-report’. The person with the pain provides the information to complete the measure about the pain. Self-report measures are used in many ways. They often involve rating pain on some kind of metric scale. A therapist might ask the patient to rate the worst pain, the least pain and the average pain in the past week. Diaries are another way to gain a prospective, subjective view of a patient’s pain if the pain is persistent or chronic. It is a helpful way to measure the impact of the pain on the patient’s life. Diaries can be relatively structured with the necessary information to record prepared in a format that is completed at regular intervals. Ratings of pain intensity, levels of rest and activity, and current mood and emotional or affective states can also be recorded.

Self-report is considered the gold standard of pain measurement because it is consistent with the definition of pain. Pain is a subjective experience, but the dilemma of self-report measures is exactly that subjective nature. They are based on the patient’s perception of her or his pain and that perception may be influenced by other factors. To illustrate, the rating that you give about the severity of your migraine in Reflective exercise 7.1 is useful only to the extent that the therapist believes that you have given an honest response.

There has been controversy about the validity of self-report data; some work has shown the level of pain reported by patients with chronic pain was unrelated to their self-report of physical disability (Patrick & D’Eon 1996). The dilemma here is that we intuitively expect that the extent of disability should be proportionately related to the severity of the pain. When they are not related in this way, we are inclined to argue that the patient’s self-report of pain intensity is exaggerated and invalid. This may be so, but actual physical performance and perceived level of physical performance may be two entirely different constructs, each of which is valid clinical information about a patient with chronic pain. It has been identified that self-report validity is limited by the lack of a normative dataset, such as would standardize clinical interpretation of pain reportage from different patients (Nicholas et al 2008). Lastly, self-report measures rely on the person’s ability to communicate about pain. Self-report is not possible for infants, young children or people with special needs that impair communication.

Observational measures

The subjective components may help in determining which type of treatment programme is most appropriate for which type of patient with pain (Strong et al 1994a). Nevertheless, observational measures may be relatively expensive as a technique since they require observation time. They may also be less sensitive to the subjective and affective components of the pain experience.

In research, observational measures have been shown to be most accurate for acute pain since pain behaviour tends to habituate as pain becomes more chronic (McGrath & Unruh 1999). There is also no behaviour that is an indicator of pain and nothing else. Clutching the abdomen may be due to pain but it might also be a spasm of nausea. To know what the behaviour signifies one may need to ask the person and that is back to self-report. The advantage of collaborative reporting between patient and observer was noted in a study by Ahlers et al (2008), wherein ICU nurses were found to underestimate critically ill patients’ level of pain in comparison to the patients’ self-assessment using a numeric rating scale.

In this way, observational measures fail to provide solely objective pain measurement. Rather, they reflect the therapist’s objective and subjective measurement of the patient’s pain. The roommate’s observational measurement of your migraine in Reflective exercise 7.1 may be affected by her or his inexperience with migraines and the observation that you are lying down and appear to be relaxing.

Physiological measures

The third category of pain measurement is physiological. Pain can cause biological changes in heart rate, respiration, sweating, muscle tension and other changes associated with a stress response (Turk & Okifuji 1999). These biological changes can be used as an indirect measure of acute pain, but biological response to acute pain may stabilize over time as the body attempts to recover its homeostasis. For example, your breathing or heart rate may have shown some small change at the outset of your migraine if the onset was relatively sudden and severe, but over time these changes are likely to return to before migraine rates even though your migraine persists. Physiological measures are useful in situations where observational measures are more difficult. For example, the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool (C-CPOT) has been developed and tested for use with critically ill adults who cannot communicate verbally (Gélinas et al 2009).

ASSESSMENT OF PAIN

In chronic pain, the World Health Organization (WHO) classifications of impairment, disability (activity and activity limitation) and handicap (participation and participation limitation) are particularly important. Assessment of impairment may be judged by pain intensity, disability by self-care, ambulation and endurance deficits, and handicap by deficits in vocational, social or familial roles (Patrick & D’Eon 1996).

As noted previously, a therapist will usually assess a patient’s pain using the most appropriate model or frame of reference for the situation. The frame of reference focuses the assessment and in turn determines what questions must be answered through measurement. In many cases a purely biomedical approach to pain assessment may be insufficient (Vlaeyen et al 1995) because it will focus on biological measurement and exclude other psychological and environmental factors. A biopsychosocial model is often advocated (Turk 1996). This model will lead to assessment that considers interaction between biological, psychological and social components in pain experience and will determine exactly what factors within each should be measured. Gélinas et al (2008) note that the selection of a tool for pain measurement must take into account such factors as the purpose of measurement, the characteristics of the participant and the conditions of administration, along with more obvious practical considerations.

Several other factors determine which model or frame of reference is most appropriate for pain assessment. These factors include acuteness or chronicity of the pain, provision of intervention as a team member or sole pain therapist, a rehabilitation focus to the service, involvement of compensation and difficulties that might complicate assessment (such as a cognitive impairment or lack of fluency in the primary language spoken at the service). Psychological, social and demographic factors have been found to be crucial in influencing the development of chronicity of pain (Polatin & Mayer 1996) and so these areas need to be included in assessment protocols.

• Ensure there is some initial time spent to establish a collaborative relationship by getting to know the person and her or his individual situation.

• Where possible, allow for the patient to expand on formal assessment items and to elaborate on her or his responses.

• Actively listen to the patient’s information and notice signals which suggest that the patient would like to talk further (e.g. hesitations, rushing over a certain aspect, comments such as ‘but you don’t need to hear more about that’).

• Try to understand the implications for the patient’s lifestyle and quality of life as much as possible.

Experienced therapists will find in the pain literature a variety of assessment models that can be used to gather information about a patient’s pain. While different models will emphasize different elements of the pain experience, some factors appear consistent between a number of assessment tools. Davidson et al (2008) undertook an examination of nine established chronic pain measures and identified seven key dimensions: pain and disability, pain description, affective distress, support, positive coping strategies, negative coping strategies and activity. Previous research by Woolf & Decosterd (1999) advocated an interview-based assessment of the patient’s pain that is similar to one previously advocated by physiotherapists (Maitland 1987). It comprises aspects of pain such as:

• Is the pain spontaneous or evoked?

• What is the nature and intensity of the stimulus if the pain is evoked?

• What is the quality of the pain?

• What is the pain distribution?

• Is the pain continuous or intermittent?

Measurement of the description of the pain

In gathering a description of the pain from a patient, several purposes are served. A baseline description of the pain allows for comparison of changes. Ideally, pain should be monitored for some time before treatment commences, and then during treatment and at the end of treatment. The brief scales, such as the numerical rating scale, have been used daily for up to 2 weeks in chronic pain programmes and the results averaged to increase the reliability of the assessment. Although this amount of assessment will provide a baseline to truly compare to changes following intervention, it is rather more than is achievable or desirable in most clinical contexts. There is considerable evidence that self-report of pain intensity is both reliable and valid (Jamison 1996).

Numeric scales

The numeric rating scale is the most popular, but visual analogue and verbal rating scales are also well used (Jamison 1996). In a study to examine the validity of a number of commonly used measures of pain intensity, the 11-point box scale emerged as the most valid compared to a linear model of pain (Jensen et al 1989). The box scale was also accurate to score. However, this study was of patients with postoperative (i.e. acute) pain. Earlier research had suggested that the numerical rating scale was best for use with chronic pain patients (Jensen et al 1986). In Peters et al (2007) reported chronic pain patients’ preference for the numerical box-21 scale for measuring pain intensity, over horizontal and vertical versions of the VAS, the box-11 scale and the verbal descriptor scale. The exception in this case was patients aged over 75 years, who were found to prefer the verbal descriptor scale. Strong et al (1991)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree