18 Approach to the Pediatric Patient with a Rash

• Rashes with fever deserve special consideration, especially if the fever has been present for more than 5 days.

• Palpable petechiae and fever are associated with many types of bacteremia and should be treated with intravenous antibiotics immediately.

• Many pediatric exanthems are benign in children but potentially devastating to pregnant women and immunocompromised patients.

• Patients who are moderately to critically ill with evidence of rash should receive targeted empiric therapy.

• The mainstay of treatment of atopic dermatitis is topical corticosteroids.

• Diaper dermatitis present for more than 3 days is usually complicated by candidal infection.

• Staphylococcal scaled skin syndrome and toxic shock syndrome require antistaphylococcal antibiotics, hemodynamic stabilization, and supportive skin care.

Introduction

Children are often brought to the emergency department with rashes ranging from the inconsequential (insect bites) to life-threatening emergencies (meningococcemia). When evaluating a rash, physicians should be systematic in the creation of an appropriate differential diagnosis, with early identification of possible life-threatening dermatologic conditions. Assessment of the distribution, morphology, and quality of the rash is of paramount importance. Detailed historical data regarding systemic symptoms and antecedent events are required. Please refer to Chapter 191 for the approach to undifferentiated rash. This chapter addresses dermatologic conditions most commonly diagnosed in pediatric patients.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Classic Exanthems and Viral Rashes

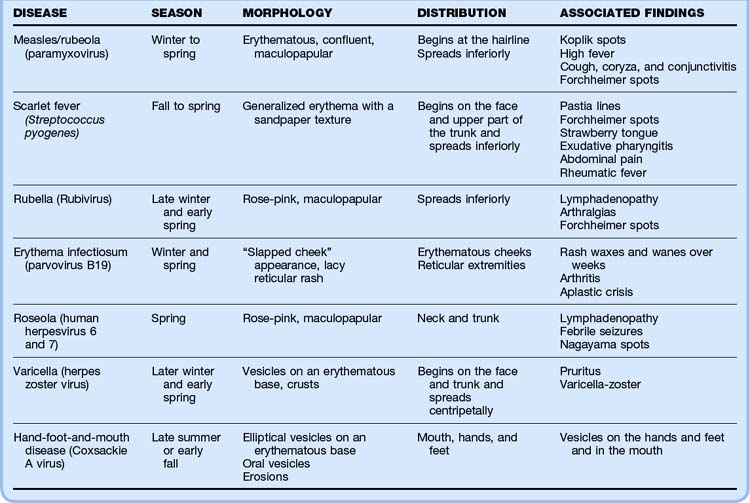

Historically, six infectious exanthems were originally described: measles or rubeola (first), scarlet fever (second), rubella (third), Dukes disease (fourth), erythema infectiosum (fifth), and exanthema subitum or roseola infantum (sixth).1 The majority of childhood exanthems are nonspecific and cannot be accurately assigned to a discrete etiologic diagnosis. These exanthems are typically self-limited and resolve spontaneously within a week.2 Table 18.1 details these classic exanthems and viral rashes.

Measles

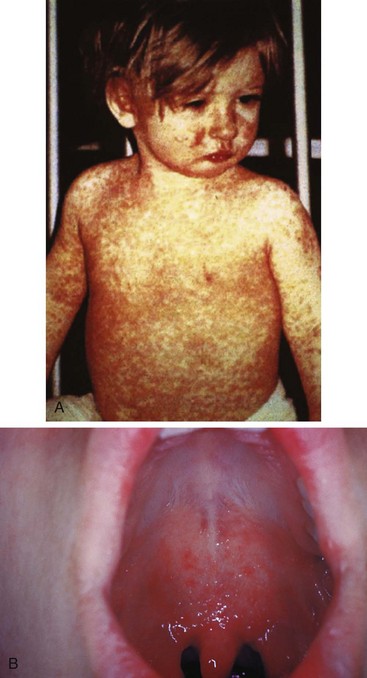

Measles is rarely seen in developed countries because of the widespread use of vaccination. However, measles continues to affect the populations of developing countries.3,4 In 1997 it was the sixth leading cause of death worldwide; it is still the leading cause of blindness in African children.5 The causative agent of measles is paramyxovirus, which has an incubation period of 7 to 12 days, and infection occurs most commonly in winter and spring.1,6 Measles is contagious 3 days before and 5 days following onset of the rash. It begins with a prodrome of gradually increasing fevers (>40° C), headache, coryza, dry hacking cough, and an impressive bilateral conjunctivitis (the three C’s). The prodrome occurs 2 to 4 days before the rash.7 Koplik spots are clustered, white lesions (“grains of salt on a wet background”) that may appear on the buccal mucosa opposite the second molars during the prodromal period (Fig. 18.1). They are pathognomonic if present.7 The erythematous, nonpruritic, maculopapular rash first appears at the hairline and behind the ears and then spreads inferiorly. As the rash involves the trunk and extremities, the discrete macules coalesce. After 1 week the rash fades.1,6 Diagnosis of measles is typically made clinically; however, laboratory diagnosis via serologic assay is available.7,8 Treatment of measles is supportive. Administration of vitamin A is associated with a reduction in risk for mortality in children younger than 2 years, as well as a reduction in postmeasles pneumonia complications.9 Complications of measles include blindness, pneumonia, laryngotracheobronchitis, otitis media, myocarditis, and encephalitis.7,10

Scarlet Fever

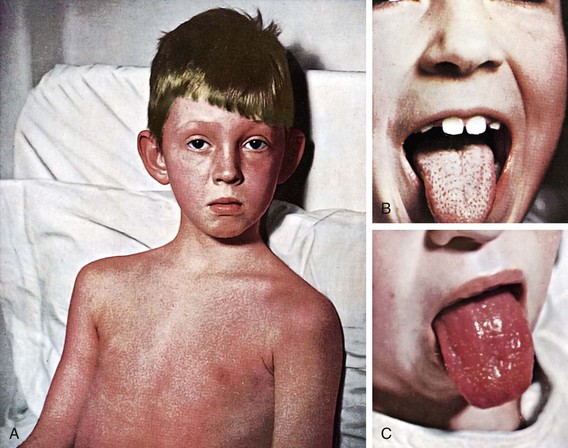

Scarlet fever, an exotoxin-mediated illness caused by infection with Streptococcus pyogenes, occurs primarily in children younger than 10 years.11 Scarlet fever is most often associated with streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis, although it can be seen following other streptococcal infections.12 Its incidence is highest during the late fall to late winter, and the incubation period is 2 to 5 days.12,13 Symptoms include an abrupt onset of fever, headache, malaise, and odynophagia with occasional vomiting and abdominal pain. This is followed by the appearance of a strawberry tongue and a bright red enanthem (oral rash) on the soft palate and uvula. These punctate, erythematous macules are called palatal petechiae or Forchheimer spots. The rash, which follows the fever by 1 to 2 days, is a generalized erythroderma with scattered pinpoint, erythematous blanching papules that have a sandpaper-like texture. Capillary fragility causes petechiae in the flexural surfaces (Pastia lines), and facial flushing with circumoral pallor is often apparent. The palms and soles are typically spared. The exanthem typically resolves in 5 days, followed 2 weeks later by postexanthematous desquamation, especially of the palms and soles.1,11 The diagnosis is made clinically but can be confirmed by streptococcus-positive throat culture.11 Penicillin remains the treatment of choice to prevent local suppurative complications and acute rheumatic fever.13 Additional complications are rare but include sepsis, acute glomerulonephritis, pneumonia, pericarditis, hepatitis, otitis media, meningitis, and toxic shock syndrome (TSS) (Fig. 18.2).11,14

Fig. 18.2 Scarlet fever.

(Courtesy Dr. Franklin H. Top, Professor and Head of the Department of Hygiene and Preventive Medicine, State University of Iowa, College of Medicine, Iowa City, IA; and Parke, Davis & Company’s Therapeutic Notes. From Gershon AA, Hotez PJ, Katz SL. Krugman’s infectious diseases of children. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2004.)

Rubella

Rubella is a relatively mild illness caused by Rubivirus that is accompanied by a maculopapular rash. The incubation period is 12 to 23 days, with the period of infectivity extending from a few days before until 7 days following onset of the rash.15 Rubella occurs most commonly in late winter and early spring.15 The prodrome is mild, if present, and consists of malaise, pharyngitis, cough, low-grade fever, coryza, and a headache. A faint pink-red maculopapular rash subsequently appears, first on the face and then with rapid caudal spread. The rash typically resolves in 3 to 4 days.15,16 The prodrome is common in adolescents and adults but is often absent in younger children. Other clinical findings include posterior cervical and occipital lymphadenopathy, Forchheimer spots, arthralgia, and neutropenia.1,16 The diagnosis is made clinically but serologic tests are available.16 Treatment of rubella is supportive. However, patients must avoid pregnant women (first 20 weeks of gestation) to prevent spontaneous abortion or congenital rubella syndrome.15 Complications of rubella include arthritis, encephalitis, and thrombocytopenia.15,17

Erythema Infectiosum

Erythema infectiosum (fifth disease) is caused by human parvovirus B19 and typically affects school-age children. It has an incubation period of 1 to 2 weeks and occurs more frequently in winter and spring.1,15,18 Children with this virus typically feel well. However, 10% of patients experience a prodrome consisting of low-grade fever, headache, sore throat, malaise, myalgia, and coryza.1,18 This prodrome is followed by a bright, fiery red macular rash across the cheeks that gives the child a “slapped cheek” or sunburned appearance. This rash lasts 1 to 4 days and then progresses to a more generalized rash with a lacy reticular pattern, most prominent on the extremity extensor surfaces. The rash may then wax and wane for a month, with various stimuli increasing its intensity.1,15 Once the rash appears, children are no longer infectious.1 The diagnosis is made clinically, but serologic tests can be used. Treatment of erythema infectiosum is supportive, but parents must keep infected children away from pregnant women and those with hemolytic anemia. High-risk groups may be treated with intravenous immune globulin (IVIG).15 Complications are rare but include symmetric arthritis of the hands, wrists, or knees and intrauterine infection and fetal death if the infection occurs during the first half of pregnancy. Children with hemolytic anemia and hemoglobinopathy (particularly sickle cell disease) are prone to transient aplastic crisis when infected with parvovirus.18–21

Roseola Infantum (Exanthema Subitum)

Roseola is the most common viral exanthem in children younger than 3 years. It is called baby measles or 3-day fever, and the causative agents are human herpesviruses 6 and 7.22,23 Roseola has an incubation period of 5 to 15 days.15,24 It is characterized by high fever for 2 to 5 days in an otherwise well-appearing child. Following dissipation of the fever, a blanching, evanescent, pink maculopapular exanthem develops on the neck and trunk. The rash typically lasts approximately 1 to 2 days. Associated symptoms include mild coryza, cough, otitis media, headache, periorbital edema, and posterior cervical lymphadenopathy.23–25 An enanthem of red papules (Nagayama spots) may be seen on the mucosa of the soft palate and uvula.23,25 The diagnosis is made clinically and treatment is supportive.15,24,26 Febrile seizures are a common complication. Other complications are uncommon but include thrombocytopenia, hepatitis, and encephalitis.15,24,27

Varicella (Chickenpox)

The incidence of varicella has decreased 90% in the last 20 years with routine vaccinations.28 Chickenpox, caused by varicella-zoster virus, is highly contagious, with a peak incidence in late winter and spring.29,30 Children 2 to 8 years of age are primarily affected. After an incubation period of 10 to 21 days, the prodrome begins with malaise, low-grade fever, cough, coryza, anorexia, sore throat, and headache.30,31 Within 1 to 2 days the skin eruption begins on the trunk and then spreads over the next week to the face (including the mucous membranes) and extremities (with sparing of the palms and soles). The lesions begin as red macules that quickly progress to discrete vesicles on an erythematous base (Fig. 18.3). The vesicles (“dew drops on a rose petal”) rapidly evolve into pustules, which umbilicate and crust over in 5 to 10 days. These lesions are intensely pruritic and characteristically seen in all stages of development at once, with resolution in 7 to 10 days.1,30 The infectivity period begins several days before onset of the rash and lasts until all the lesions are completely crusted.31 The diagnosis is made clinically; however, a Tzanck preparation demonstrating multinucleated giant cells or other viral assays can be used for confirmation.1,30 Treatment is usually supportive, with management of constitutional symptoms and pruritus and prevention of secondary infection.1,30 Wet dressings, soothing baths, calamine lotion, and antihistamines may provide symptomatic relief. Acyclovir may be effective in treating varicella and preventing systemic complications in immunocompromised children. The role of acyclovir in otherwise healthy children remains unclear.32,33 In normal, immunocompetent children, symptoms are mild and serious complications rare. Secondary bacterial infections should be treated with antibiotics directed at Staphylococcus aureus or group A β-hemolytic streptococci (cephalexin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, or dicloxacillin).1 Mupirocin may be appropriate for minor, localized secondary infections. Other complications include pneumonia, vasculitis, and encephalitis.34 Immunocompromised children and patients receiving chronic steroid treatment are more prone to extensive skin eruptions, varicella pneumonia, and severe constitutional symptoms.35 Maternal infection (first trimester) can result in congenital varicella syndrome. Perinatal maternal infection can result in disseminated herpes of the neonate.30,31 Perinatal varicella carries a mortality of up to 30%.31

Picornaviral Exanthems

Picornaviruses are a family of RNA viruses that cause a variety of illnesses. Common viruses include coxsackieviruses, echoviruses, and enteroviruses. These are the most common summertime exanthems.1,22 Disease expression ranges from exanthems (younger children) to aseptic meningitis (older children). The characteristic exanthem is typically morbilliform (“measlelike”).1 Associated symptoms include upper respiratory symptoms, conjunctivitis, fever, vomiting, and diarrhea. Complications include pericarditis, myocarditis, pleurodynia, parotitis, hepatitis, pancreatitis, and encephalitis.1

Hand-Foot-and-Mouth Disease

This enteroviral exanthem is caused by Coxsackie A virus and enterovirus 71. It is characterized by oral vesicles, followed by vesicles on the hands and feet and may also include the buttocks.15 Hand-foot-and-mouth disease has an incubation period of 3 to 6 days.36 Patients are highly contagious 2 days before and 2 days following onset of the eruption. There is a brief prodrome consisting of low-grade fever, malaise, anorexia, and odynophagia. The oral lesions begin as small red macules that evolve into vesicles measuring 2 to 20 mm. These vesicles rupture rapidly and leave painful erosions. Children often refuse to eat or drink because of pain, and dehydration is a potential complication.15,36 The lesions found on the hands and feet begin as macules and papules that evolve into flat-topped, elliptical vesicles with an erythematous base. The diaper area may be affected in infants.1 The diagnosis is made clinically, and treatment is symptomatic. Anesthetic mouthwash may provide relief from painful oral ulcers.15 Rare complications include myocarditis, pneumonia, meningoencephalitis, and aseptic meningitis. Infection during the first trimester of pregnancy may result in spontaneous abortion (see Table 18.1).15

Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

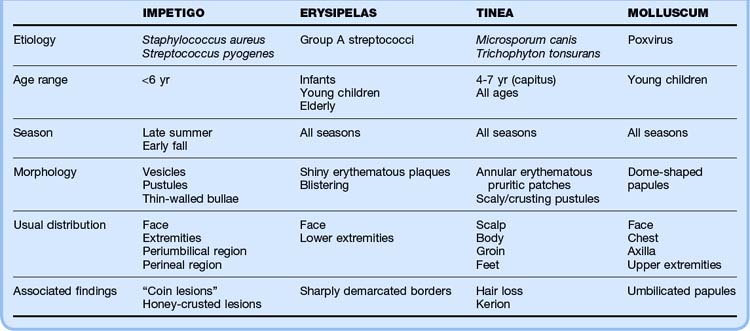

These infections represent the most common bacterial, fungal, and viral infections of childhood. Table 18.2 details these pediatric skin and soft tissue infections.

Impetigo

Impetigo is a superficial bacterial skin infection typically caused by S. aureus or S. pyogenes and is the most common cutaneous infection in children.1,32 Impetigo is most prevalent in children younger than 6 years and typically occurs in late summer and early fall secondary to microscopic breaks in the epidermal barrier.12,37,38 Additional contributing factors include warm humid climates, overcrowding, and poor hygiene.12 Impetigo is highly communicable.37

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree