APPROACH TO THE INJURED CHILD

MEGAN LAVOIE, MD AND MICHAEL L. NANCE, MD

RELATED CHAPTERS

Resuscitation and Stabilization

• A General Approach to Ill and Injured Children: Chapter 1

• Interfacility Transport and Stabilization: Chapter 6

Trauma Emergencies

• Abdominal Trauma: Chapter 111

• Genitourinary Trauma: Chapter 116

• Musculoskeletal Trauma: Chapter 119

Injuries are commonly seen in the emergency department (ED), thus clinicians caring for children and adolescents in this setting should be prepared to manage a range of injuries. Although pediatric trauma victims have needs distinguishing them from adults, it is only since the mid-1990s that investigators have begun to systematically look at the care of the injured child. The goal of this chapter is to help prepare ED clinicians for the triage, assessment, and initial management of pediatric trauma patients along the spectrum of minor to life-threatening injuries.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Injury remains the leading cause of death in children 1 to 19 years old in the United States accounting for more than 50% of all childhood deaths. In 2012, more than 11,000 children and adolescents <19 years died from unintentional and nonaccidental injury. Nearly 22 million children are injured annually; and there are approximately 10 million primary care office visits, 9 million ED visits, and 500,000 hospitalizations yearly. Injuries are the leading cause of ED visits and account for approximately one-third of all visits for children younger than 15 years. It has been estimated that the cost of unintentional pediatric injuries is $347 billion every year: $17 billion in medical costs, $72 billion in future work lost, and $257 billion in lost quality of life.

Motor vehicle crashes continue to be the most common cause of injury-related death and resulted in >4,000 deaths in 2012. Rates for childhood homicide tripled and rates for childhood suicide quadrupled between 1950 and 1993; and are the second and third leading cause for death in ages 0 to 19 years respectively. In 2012, firearms were reported to be involved in 2,683 deaths. Homicide rates in children have two peaks: from age 0 to 3 years and from 14 to 18 years. In black teenagers, homicide from firearms is the leading cause of death. Although less fatal, falls, drowning, poisoning, and fire/burn injuries are significant causes of morbidity.

The societal impact of years of life lost from childhood unintentional injury is staggering. In a 10-year period, more than 50,000 unintentional injury deaths are reported in children <5 years. Annually, there are >70,000 injuries as a result of automobile crashes in the same population. Crash mortality statistics show that the youngest occupant in an automobile is the most vulnerable to injury. Children from 5 to 9 years of age are most likely to be pedestrian injury victims. Overall, pediatric pedestrian injury accounts for 46% of motor vehicle fatalities. Boys in densely populated urban areas represent the largest group at risk. Injury from bicycle crashes is particularly common in children 6 to 16 years. Societal violence as a cause of death in children is increasing at an alarming rate. An estimated 8,625 child maltreatment fatalities occurred in the 50 states and the District of Columbia from 1999 to 2002.

Blunt trauma is the predominant mechanism of major injury in children; only 10% to 20% experience penetrating injury. Although the mortality rate for children requiring hospitalization is less than 1% in many pediatric trauma centers, 80% of all childhood trauma deaths occur at the scene or in the ED. As many as 18% of hospital trauma deaths are avoidable with correct diagnosis and treatment. Brain injury is responsible for 80% of trauma mortality. Failure to secure the airway is the most common cause of preventable death. Multisystem injury occurs in more than 50% of victims and requires a coordinated approach by a team of specialists with immediate access to varied diagnostic and treatment modalities including the OR, ICU, or rapid skilled transport.

Attention to pediatric differences in anatomy and physiology of children is key: multisystem trauma is more likely as impact is distributed more widely throughout the body; compensatory mechanisms to volume loss make hypotension a late finding; greater surface area relative to body size causes increased heat and insensible fluid loss. Children have higher energy requirements, and fluid and nutrition requirements vary by age and stage of growth. Finally, varying developmental stages can present challenges in assessment.

This chapter provides a framework for the emergency management of pediatric injuries, isolated and multiple, mild to life-threatening, with emphasis on the rapid, systematic evaluation by the ED and trauma team specialists.

SPECTRUM OF TRAUMA AND INITIAL TRIAGE

Trauma causes injuries that range from mild to life- or limb-threatening. During initial triage several categorizations of injury are useful: (1) extent—multiple or isolated; (2) nature—blunt or penetrating; and (3) severity—mild, moderate, or severe.

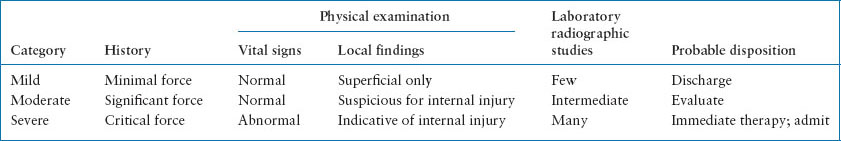

TABLE 2.1

CLASSIFICATION AND DISPOSITION OF TRAUMA BY SEVERITY

Surgeons have standardized the definition of multiple trauma as documented significant injury to two or more body areas in order to meaningfully compare patient outcomes. For the ED clinician, multiple trauma is defined as apparent injury to two or more body areas of any severity (forehead laceration and forearm fracture). Isolated trauma involves one anatomic region of the body regardless of severity. The distinction between isolated and multiple trauma may be challenging as (1) serious injuries often evolve over time; (2) children may be difficult to examine because of development stage; (3) injury may have been intentional so true mechanism is unclear; (4) drugs or alcohol exposure may coexist. Differentiation between isolated and multiple trauma is thus a dynamic process, and the emergency physician’s first impression may change as new evidence accumulates. The nature of the injury, blunt or penetrating also guides the evaluation based on the specific force and the expected internal injuries. Table 2.1 provides classification of injury severity based on history and physical examination, as well as a general schema for disposition, based on extent of laboratory and imaging required to evaluate the patient. Initial severity categorization depends on the history and the physical examination. Assessment of severity is essential in the ED as it determines the need for immediate intervention, the extent of diagnostic evaluation, and patient disposition.

ORGANIZATION OF THE TRAUMA SERVICE

The regionalization of trauma care in the United States continues to evolve. In many areas, hospitals are stratified on the basis of their capability and desire to care for the multiply injured child; in other areas, no such stratification exists. The goal of trauma center designation, under the guidance of the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, is the triage of injured children to appropriate, qualified facilities. Because of the relative scarcity of pediatric trauma centers, approximately 70% of injured children still receive care in general facilities. Another 77% of all children are within 60 minutes of a pediatric trauma center by air or ground transportation. The availability of rapid pediatric transport services and pre-existing transfer agreements may accelerate the needed regionalization of pediatric trauma care.

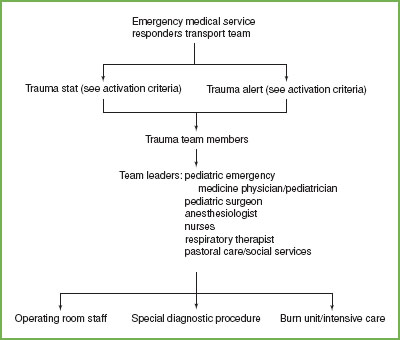

The effective management of pediatric trauma requires the integration of a multidisciplinary team, including surgeons, emergency physicians, critical care physicians, emergency and intensive care nurses, respiratory therapists, radiologists, and various subspecialty services (neurosurgery, orthopedic surgery, anesthesia etc.), as well as the ready availability of diagnostic and operating room resources. Each institution must develop its own organizational response for pediatric trauma with a well-established chain of command and a designated leader, a responsibility that may change hands as additional personnel arrive for resuscitation in the ED. The leader accepts responsibility for patient care and organizes the multiple specialists needed to care for the patient with multisystem injury. Such organization begins at the scene of an injury and EMS transport, continues throughout patient triage after initial evaluation, and care once the patient arrives in the ED. After ED resuscitation and stabilization, the decision to transfer the child to a hospital with a higher level of capability, admit to the ward or to the intensive care unit, or proceed to the operating room is made by the team leader after consultation with the specialists involved. If it becomes clear that the predominant injury is to a single-body system, it may be appropriate for the team leader to transfer patient care responsibility to the designated leader of a given subspecialty (e.g., orthopedics, neurosurgery). Figure 2.1 demonstrates a flow diagram of a response to the seriously injured child, an example of organizational schema put into action when or before a victim of serious trauma arrives in the ED. Mock resuscitations with members of the multidisciplinary trauma team allows a venue to practice resuscitation interventions and utilize special bedside equipment, assures that necessary personnel and processes are in place, and importantly allows team discussion around leadership, roles, and communication.

FIGURE 2.1 Sample flow diagram of a response from the emergency medical services team that is placed into action when or before a victim of serious trauma arrives in the emergency department.

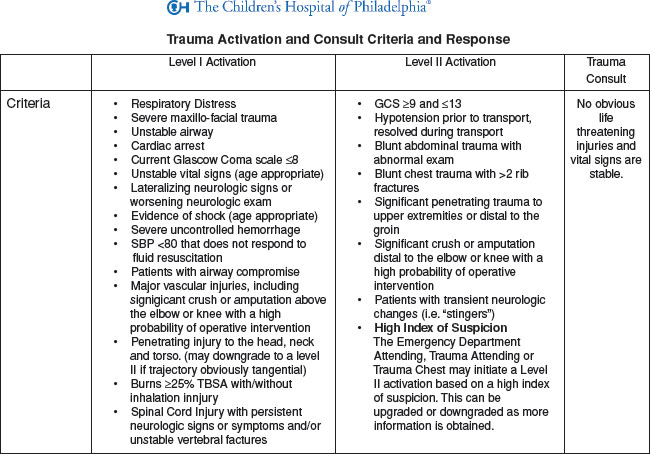

FIGURE 2.2 Trauma Activation and Consult Criteria at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Upon notification of a patient’s impending arrival, the ED physician determines the risk for severe injury, and whether activation of the trauma team is necessary. Early activation is optimal to prepare for the patient arrival. The three levels of trauma team activation (variably named) include trauma stat (major trauma), trauma alert (moderate trauma), and trauma consult (minor trauma). Notification necessitates an in-the-field determination of likelihood of severe injury. Historically, trauma activation criteria have been based on mechanism of injury. In a mechanism of injury trauma activation system, patients who meet certain criteria are automatically triaged as major traumas. However, triaging systems based on mechanism have led to “overtriaging” of pediatric trauma patients, leading to unnecessary use of personnel and resources and costs, as well as disruption of other hospital care and procedures. For injured pediatric patients, activation based on anatomic and physiologic has been shown to be a more accurate method of triaging patients (see Fig. 2.2).

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT

Triage

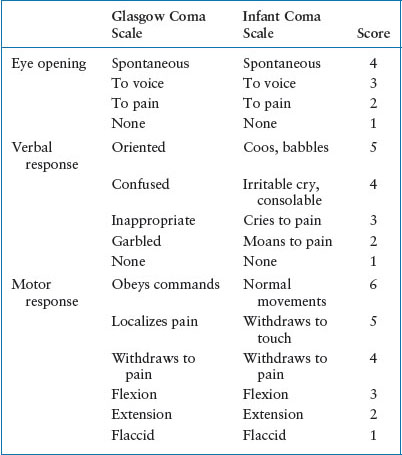

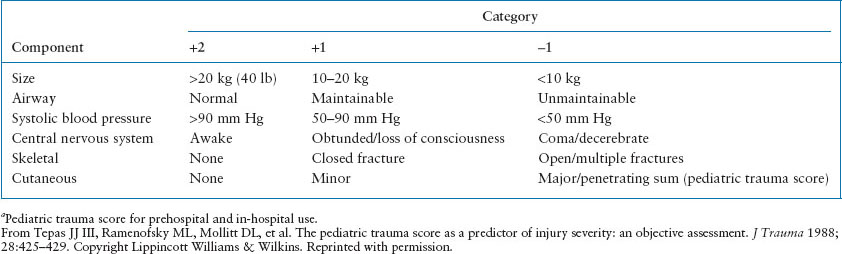

Definitive care may occur in the prehospital setting (e.g., endotracheal intubation), in the ED (e.g., chest tube placement), in the intensive care unit, or operating room. Triage is a process of patient assessment, prioritization of treatment, and selection of appropriate treatment location. In the early stages of patient assessment, the precise diagnosis of anatomic injury is often impossible. To identify patients with a potential for major morbidity or death, various physiologic scoring systems have been developed. The most useful are the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (see Table 2.2), the Trauma Score (TS, which includes GCS) and the Pediatric Trauma Score (PTS) (see Table 2.3). Prehospital triage to a designated pediatric trauma center is indicated in any patient with a GCS <12, a TS <12, or a PTS <8. Field studies of the TS showed that at night, it is difficult to assess capillary refill and respiratory effort. Therefore, the most common tool used in prehospital triage is the revised trauma score (RTS), which deletes these two variables. Triage to a pediatric trauma center is then indicated for any of the following criteria: GCS <12, low systolic blood pressure, or abnormal respiratory rate for age. In the ED setting, a complete TS or PTS is usually obtained. The RTS is the most commonly used tool when evaluating outcomes. The PTS emphasizes the importance of patient size and ability to maintain the airway. Studies confirm the validity of the PTS as a predictor of outcome: 9% mortality for PTS >8 and 100% mortality for PTS <0. From 0 to 8, there is a linear relationship between lower PTS and an increased potential for mortality. Nevertheless, studies comparing TS, RTS, and PTS do not show any statistical advantage of PTS for the purposes of triage. In fact, many children with significant solid organ injuries have a normal PTS. Therefore, whichever physiologic scoring system is selected, it should be used consistently and sequentially to measure how the patient is responding to interventions.

TABLE 2.2

PEDIATRIC COMA

TABLE 2.3

PEDIATRIC TRAUMA SCOREa

Initial Evaluation

Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) established by the American College of Surgeons outlines a standard approach to evaluation and treatment of the trauma victim. After prehospital evaluation and care, the injured child is transported to the hospital. Trauma level notification based on physiologic criteria from the scene determines the need for trauma team activation. The indication for team activation varies depending on local personnel but should include all children with anatomic or physiologic signs of significant injury (Fig. 2.2). In the ED assessment includes a primary survey, resuscitation, secondary survey, and subsequent transfer to definitive care (Table 2.4). A rapid, reproducible schema of immediate, simultaneous, and subsequent evaluation and treatment principles are applied to every child who may potentially have major or multiple trauma (Table 2.5). The principles of crisis resource management are utilized to guide the flow of the evaluation and resuscitation. Two key principles are followed in the initial assessment of the trauma patient. First, if any physiologic threat to the patient is identified, this threat is treated immediately. The order of priority is airway, breathing, circulation, disability, exposure and environment (ABCDE) (Table 2.6). In reality, with a highly organized trauma team, activities continue in parallel, rather than in series. Second, if at any point in the patient’s secondary survey or subsequent care there is unexpected physiologic deterioration; the primary survey is rapidly repeated in order of priority (ABCDE).

Primary Survey

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree