Approach to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Michael J. Barry

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a common condition among older men, causing morbidity primarily through lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). The primary physician should attempt to distinguish LUTS due to BPH from the other causes of such symptoms, objectively determine symptom severity, and, when the symptoms are bothersome enough, work with the patient on a therapeutic approach to reducing symptoms while minimizing side effects. For patients who elect watchful waiting or medical therapy, regular follow-up should be instituted to monitor for symptom changes or BPH complications. The treatment of BPH has changed substantially in recent years, with increasing emphasis on nonsurgical approaches. The result is an expanded role for primary care providers in BPH management.

Pathophysiology

BPH arises from nodular hyperplasia of prostatic stromal and glandular elements. Growth begins in the periurethral glandular tissue. As these nodules expand and coalesce over years, the true prostatic tissue is compressed outward and forms a “surgical capsule” around the adenomatous hyperplasia. The etiology of age-related prostatic hyperplasia is unknown, although it is reasonably well-established that androgenic stimulation at the cellular level has a major influence. A better understanding of these influences on prostatic hyperplasia has led to pharmacologic interventions that can alter the natural history of the disease.

As the gland enlarges, urethral resistance to urine flow increases and bladder muscle hypertrophy ensues. Detrusor instability may develop, and emptying may become incomplete. The resulting residual urine predisposes to infection. Bladder herniations can form between the thickened, overlapping muscular bands that comprise the detrusor. These diverticula may further predispose to infection. The role of the bladder in contributing to bothersome symptoms among men with bladder outlet obstruction is becoming increasingly appreciated.

Some men with BPH develop acute urinary retention. The hyperplastic prostate is highly vascular and predisposed to bleeding; painless hematuria can occur, but alternative causes, particularly malignancy, need to be considered.

The late-stage complications of chronic retention caused by BPH include hydroureter, hydronephrosis, and renal failure. Fortunately, these complications are rare.

Clinical Presentation and Course

BPH manifests clinically chiefly through LUTS. Although BPH is the most common cause of such symptoms among older men, other diseases can cause them also. The old term prostatism implies a diagnostic specificity to these symptoms that does not in fact exist; this term should be avoided. Simplistically, voiding symptoms (such as a weak stream, straining, hesitancy, and intermittency) have been attributed to mechanical bladder outlet obstruction, whereas filling symptoms (such as frequency, nocturia, and urgency) have been attributed to secondary detrusor instability. In reality, the situation is much more complex; the way in which the histologic process of BPH eventually leads to symptoms is in fact poorly understood. The severity of LUTS correlates poorly with prostate size and urodynamic measurements of the severity of bladder outlet obstruction, and some treatments (such as microwave thermotherapy) can reduce symptoms considerably without having much effect on these parameters.

It is quite common for patients to have a waxing and waning symptomatic course, with gradual deterioration through many years. Sometimes, urinary tract infection or acute retention is the first indication of bladder outlet obstruction secondary to BPH.

The digital rectal examination of the prostate provides a rough estimate of overall gland volume but is of little help in assessing the degree of bladder outlet obstruction. Severity can be assessed by symptom frequency and a few basic laboratory studies (see later discussion). Clinicians tend to underestimate prostate size, so if the prostate feels enlarged, it usually is.

Assessing Severity of Symptoms

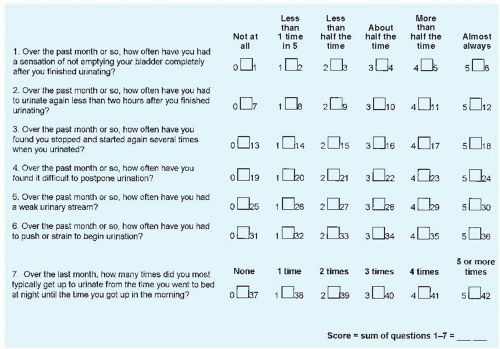

In older men presenting with LUTS believed likely to be caused by BPH, the clinician should first objectively document symptom severity. The seven-item American Urological Association (AUA) symptom index is a quick, self-administered questionnaire that is widely used for this purpose (Fig. 138-1). Scores on individual questions can be summed to yield an AUA symptom score ranging from 0 to 35. Scores of 0 to 7 represent mild symptoms, 8 to 19 moderate symptoms, and 20 to 35 severe symptoms. Some clinicians use voiding diaries in addition to symptom scores to further assess patients’ symptoms, particularly when nocturia is a prominent complaint. It is especially important for clinicians to determine the extent to which the patient is bothered by his symptoms.

A urinalysis should be performed to check for infection or hematuria. A creatinine determination can assess renal function but will seldom change management and is not recommended in recent guidelines. Measurements of postvoid residual urine can be made by catheterization (>50 to 100 mL of residual urine is abnormal) or, less invasively, by transabdominal ultrasonography. However, these measurements are poorly reproducible in individual patients, and they probably help only if they are persistently and grossly increased.

Urinary flow studies are commonly performed by urologists. These tests do not require catheterization and are particularly useful in assessing patients whose presentations are atypical (e.g., younger patients or men with dominantly filling symptoms). A normal peak flow rate (>15 mL/s) in the setting of LUTS should prompt further evaluation for alternative explanations. However, men with true bladder outlet obstruction may sometimes maintain normal flow rates by generating high bladder pressures. Similarly, men with hypotonic bladders may have low flow rates without outlet obstruction. A voided volume of less than 150 mL may produce a falsely low peak flow rate.

Imaging studies are not routinely necessary in typical cases of LUTS attributed to BPH. Radiographic assessment of the bladder and upper urinary tract is not recommended unless an elevated creatinine level, hematuria, or another specific indication is present. If necessary, transabdominal ultrasonography can be used to exclude hydronephrosis and assess the postvoid residual volume. Similarly, cystourethroscopy should be performed only when specifically indicated (e.g., prior genitourinary instrumentation, hematuria). More sophisticated urodynamic studies (cystometrics and pressure-flow studies) are best reserved for patients with conflicting results on simple tests (e.g., bothersome symptoms but a normal flow rate), neurologic disease, or prior unsuccessful prostatectomy.

Assessing Significance of Symptoms

It is essential that the physician assess the impact of symptoms on the patient’s quality of life because the individual patient may be willing to accept a given level of symptomatology and a small risk for future BPH complications to avoid medications or surgery.

Checking for Prostate Cancer

When the digital rectal examination findings are not suggestive of prostate cancer, a test for serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) can be considered for men with LUTS attributable to BPH. In the recent Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial, the sensitivity of PSA for histologic prostate cancer at the traditional cut point of 4.0 ng/mL was only about 25%, and it was about 40% for moreconcerning cancers of Gleason grade 7 or higher. Specificity was 90% or higher in this study of unselected older men but is lower among men with symptoms due to BPH because benign prostatic enlargement itself can raise serum PSA. Moreover, the prior probability of subclinical prostate cancer does not seem to be appreciably elevated in the presence of LUTS. Even advocates of PSA screening do not advise the test for men with less than a 10-year life expectancy (ages 75 years and older for men with average comorbidity), given its dubious effect on mortality among these men. European guidelines for the diagnostic evaluation of men with LUTS, recently endorsed by an AUA guideline, suggest discussing a PSA test for men being evaluated for LUTS if life expectancy is greater than 10 years and a diagnosis of prostate cancer would modify the patient’s management. Men with LUTS should understand that they run a risk of harboring coincidental prostate cancer and that further tests are available if the patient and his physician wish to screen for prostate cancer (see Chapter 126 for further discussion about prostate cancer screening).

Predicting Prognosis

PSA level, in the absence of a larger cancer, also provides a rough estimate of prostate size. The following PSA cut points have about 70% sensitivity and specificity for a prostate size greater than 40 mL: greater than 1.6 ng/mL for age 50 to 59 years, greater than 2.0 ng/mL for age 60 to 69 years, and greater than 2.3 ng/mL for men age 70 to 79 years. Men with larger prostates and higher baseline PSA levels (particularly >3.2 ng/mL) have a higher probability of symptom progression over time, as well as higher risks of acute urinary retention and progression to prostatectomy.