INTRODUCTION

Anorectal disorders range from simple to complex and can manifest signs and symptoms of underlying serious local or systemic disorders that may be life threatening. Precise causes may be difficult to determine; thus a focused history and careful examination can narrow the differential diagnosis and aid timely and appropriate management.

ANATOMY

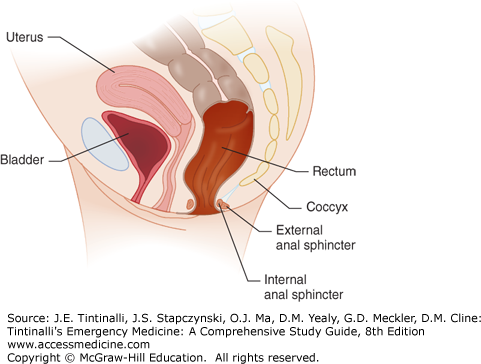

The rectum begins at the S3 vertebral body and descends for about 13 to 15 cm becoming the anus, comprised of the anal canal, anal verge, and anal margin. The rectum narrows and traverses through the muscular pelvic floor, at the level of the levator ani and coccygeal muscles, and becomes the anal canal, 4 cm in length, surrounded by the anal sphincter muscle (Figure 85-1).

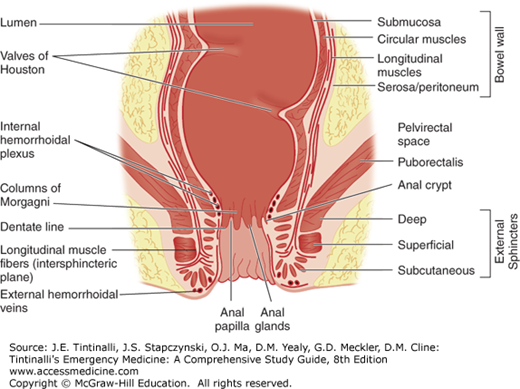

The dentate line marks the junction of these two structures as the anal canal continues more distally joining the perianal skin at the anal verge (Figure 85-2). The anal canal mucosa consists of stratified squamous epithelium and contains no hair follicles or sweat glands. At the anal verge, the anoderm thickens and includes hair follicles and other cutaneous appendages. Proximal to the dentate line, the rectal ampulla narrows to conform to the opening of the anal canal. In doing so, its mucosa takes on a pleated appearance, forming 8 to 14 convoluted longitudinal folds: the columns of Morgagni. Each adjacent column is connected at the dentate line by a flap of mucosa that forms a small anal crypt, normally 1 to 3 mm deep. Anal sepsis, cryptitis, perianal abscesses, and fistulas result from inflammation, obstruction, and infection of the crypts and glands. The anal wall is a continuation of the usual layers of the wall of the colon and rectum, and the innermost mucosal lining continues to the anal verge. Just proximal to the dentate line, the mucosa transitions from rectal columnar to cuboidal to squamous epithelium. The submucosa, which normally contains the bulk of the bowel’s blood vessels and autonomic nerves, thickens considerably proximal to the dentate line. The superior hemorrhoidal artery, from the internal mesenteric artery, supplies the proximal two thirds of the rectum, whereas the middle hemorrhoidal artery, from the internal iliac artery, supplies the distal one third of the rectum. The inferior hemorrhoidal artery supplies the anus but also supplies the rectum by a submucosal network. The venous and lymphatic system mirrors the arterial supply. The superior rectal vein drains into the portal system, whereas the middle rectal vein drains into the inferior vena cava. The inner circular muscle layer of the rectum thickens considerably as it terminates distally in the anorectum to form the involuntary internal sphincter muscles. The more attenuated longitudinal muscles of the rectum extend caudally, blending with fibers of voluntary skeletal muscles from the levator ani and external sphincter groups, to form the intersphincteric space (Figure 85-2).

The external sphincters are voluntary skeletal muscles and are actually a caudal extension of the puborectalis muscle, which interacts with the levator ani muscle, forming the pelvic floor. The puborectalis, the proximal external sphincters, and the internal sphincters form the ring of muscles that one palpates when performing a digital examination of the anorectum.

Lateral to the external sphincters is the ischiorectal space, and superior to the levator ani is the supralevator (pelvirectal) space, where deep, life-threatening infections can occur. Inferior mesenteric and para-aortic nodes drain the proximal two thirds of the rectum, whereas the lower one third of the rectum and proximal anal canal are drained by both the inferior mesenteric nodes and the internal iliac nodes. The inguinal nodes usually drain lymphatics distal to the dentate line. Proximal to the dentate line, the anus is supplied by the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves, yet is devoid of somatic pain fibers, unlike distal to the dentate line, where somatic fibers are present. Parasympathetic nervous stimulation (S2 to S4) contracts the rectal wall and relaxes the internal anal sphincter, whereas sympathetic stimulation (L1 to L3) maintains continence through rectal wall inhibition and contraction of the internal anal sphincter.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

No matter how much historical information is obtained, no definitive diagnosis can be made without a careful examination of the anus and rectum. Patient education before and during the examination will be helpful in obtaining maximal cooperation. The lateral or Sims position is the most common position for routine digital rectal examination and anoscopy. This position is preferred for the elderly or pregnant women. Elevating the upper buttock provides better exposure of the perianal area. In debilitated patients, one may have to perform the examination with the patient in a supine, lithotomy position. Examining a patient placed in the knee-chest position requires a cooperative patient who is not too ill or in too much distress.

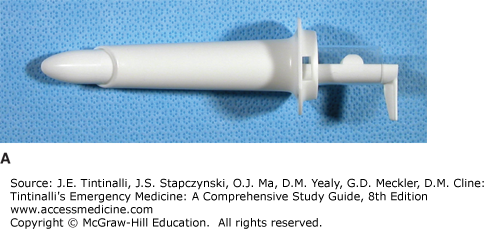

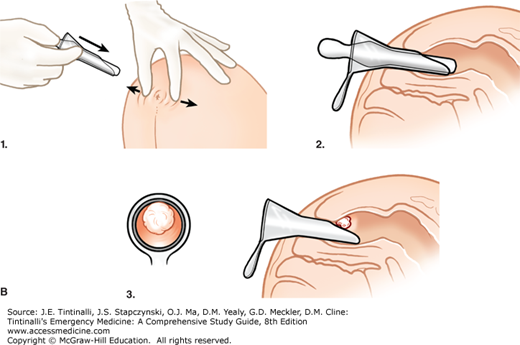

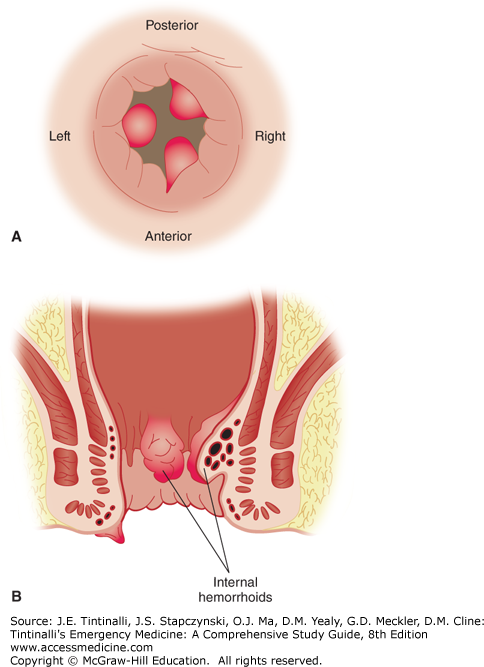

A digital examination of the entire inner wall with a lubricated index finger should always be performed before doing any endoscopic procedure. In men, palpate the prostate to determine its size, texture, and tenderness or if masses are present. In women, palpate the posterior vaginal wall for a mass, rectocele, or rectovaginal fistula. Note anal tone and sensation. The anal mucosa, dentate line, both external and internal hemorrhoids, fistulas and fissures, condyloma, and distal rectal mucosa can be evaluated with the use of an anoscope (Figure 85-3A). No bowel preparation is needed for anoscopy, and cultures can be obtained. Suction and a good light source should be available. After performing a digital examination and determining that the patient will tolerate passage of an anoscope, introduce a well-lubricated, lighted anoscope with the obturator in place. Next, remove the obturator, and gently rotate as needed to view the anorectum circumferentially while withdrawing the anoscope (Figure 85-3B). After visual inspection, ask the patient to bear down to detect any rectal mucosal prolapse.

ANAL TAGS

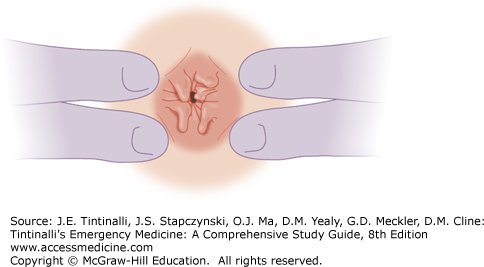

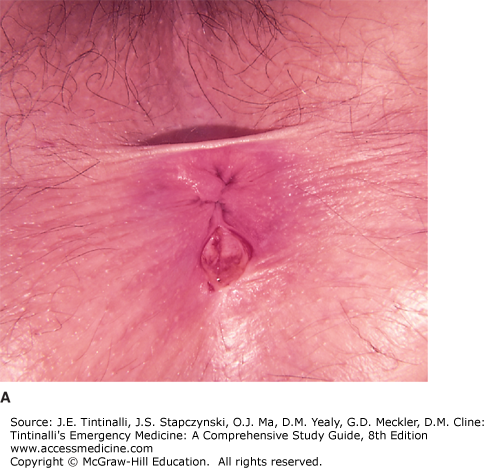

Skin tags are minor projections of skin at the anal verge and are sometimes residuals of prior hemorrhoids (Figure 85-4).

Skin tags are usually asymptomatic, but inflammation may cause itching and pain. Skin tags covering anal crypts, fistulas, and fissures are called “sentinel tags.” Surgical referral for excision and/or biopsy is warranted because inflammatory bowel disease may be associated with sentinel tags.

HEMORRHOIDS

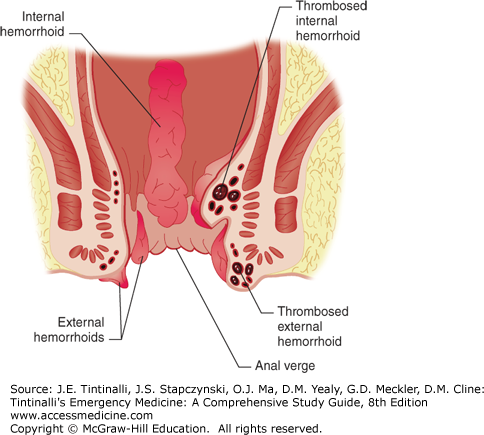

Hemorrhoids are vascular cushions that become enlarged and distally displaced within the anal canal. Current theory suggests that there is anal canal sliding and that hemorrhoidal formation occurs when the supporting tissues of these cushions deteriorate.1 Consequently, the downward displacement of these cushions causes the internal and external hemorrhoidal plexuses to become excessively engorged, referred to as hemorrhoids—one of the most common problems afflicting human beings (Figure 85-5).

Hemorrhoids may become inflamed, thrombosed, prolapsed, ulcerated, or ischemic. Internal hemorrhoids originate proximal to the dentate line, from terminal branches of the superior rectal artery. They are constant in their location, coursing longitudinally at the right posterolateral, right anterolateral, and left lateral positions; 2-, 5-, and 9-o’clock positions, when the patient is viewed prone (Figure 85-6A). Commonly, they are single and are located at the 5-o’clock position. Internal hemorrhoids are not readily palpable and can best be visualized through an anoscope. Their appearance is consistent with the columnar epithelial surface of the surrounding anal canal (Figure 85-6B). External hemorrhoids, distal to the dentate line, are located anywhere along the anoderm, form as a result of dilatation of veins at the anal verge, and can be seen at external inspection. Their appearance is consistent with the stratified squamous epithelium of the surrounding anoderm, which has exquisite sensory innervation.

Enlarged hemorrhoids are associated with constipation and prolonged straining at stool, frequent diarrhea, and older age. Increased abdominal pressure may cause obstruction of venous return and engorgement of the hemorrhoidal plexus. Consider inflammatory bowel disease in patients with frequent diarrhea and hemorrhoids. Hemorrhoidal veins can have high resting pressures and are devoid of valves, and as patients age, the supportive connective tissue surrounding the vasculature diminishes. Hemorrhoids can develop during pregnancy and may be the result of sustained increased pressure on the venous drainage of the rectum. Increased portal pressure, from chronic liver disease, may produce marked dilatation and varix formation, distinct from true hemorrhoids, resulting in bleeding that can be extremely difficult to control. Tumors of the rectum and sigmoid colon, often associated with constipation, tenesmus, and incomplete evacuation, may cause hemorrhoids. Although the most common cause of bright red rectal bleeding is hemorrhoids, tumors must be ruled out as a cause of rectal bleeding in patients >40 years of age. Ascites, ovarian tumors, distended bladders, and excessive fibrosis from radiation therapy may contribute to the formation of external hemorrhoids. Hemorrhoidal bleeding is usually limited, with the bright red blood on the surface of the stool, on the toilet tissue, or noted at the end of defecation, dripping into the toilet bowl. When patients describe the passage of blood clots, one should suspect colonic lesions. Chronic slow blood loss detected on fecal occult blood testing resulting in anemia requires further investigation. Hemorrhoids themselves generally do not cause pain unless they are thrombosed or are strangulated fourth-degree internal hemorrhoids. If the patient complains of pain, but on examination the hemorrhoids are not thrombosed, suspect perianal or intersphincteric abscesses or anal fissures. Thrombosed external hemorrhoids are painful and are often described as a burning perianal lump, and they usually exhibit a bluish-purple discoloration (Figure 85-7). Hemorrhoids may become more prominent with a Valsalva maneuver. As hemorrhoids increase in size, they may prolapse, requiring periodic reduction by the patient. Pain can be quite severe at the time of defecation and usually subsides with time.

Uncomplicated internal hemorrhoids are painless due to visceral innervation and lack of sensory innervation. Anoscopy reveals bulging, purple-colored veins at the distal rectum or anal canal (Figure 85-8). Often a chief complaint is painless, bright red rectal bleeding with defecation. Internal hemorrhoids may be palpable on digital examination when thrombosed or prolapsed.2 Nonreducible, prolapsed, internal hemorrhoids may become thrombosed and strangulated. They appear dark red, exhibit rectal bleeding, and cause exquisite pain and possibly urine retention. Ulceration, necrosis, gangrene, sepsis, and hepatic abscess formation may ensue. Internal hemorrhoids are classified by the amount of prolapse into the anal canal (Table 85-1).

| Grade I: Luminal protrusion above dentate line | Do not extend below dentate line and do not prolapse, cause painless bleeding |

| Grade II: Prolapse with spontaneous reduction | Prolapse during straining |

| Grade III: Prolapse requires manual reduction | Prolapse during straining |

| Grade IV: Prolapse-nonreducible | Can result in edema and strangulation |

Mucous discharge and pruritus ani may be seen with luminal prolapse2 (Figure 85-8).

Conservative therapy with warm baths is often successful for mild to moderate symptomatic grade I and II internal hemorrhoids. Manual reduction of grade III internal hemorrhoids and warm baths (which decrease sphincter pressures) for at least 15 minutes three times a day and after each bowel movement are the most effective ways to relieve symptoms. After the bath, the anus must be dried gently but thoroughly to avoid maceration of the perianal skin. Topical analgesics and steroid-containing ointments may provide relief. The patient should not sit on the commode for a prolonged period. Bulk laxatives and stool softeners should be used after the acute phase is treated. Avoid the use of laxatives causing liquid stool, because cryptitis and anal sepsis can result. A high-fiber, low-fat diet, with increased water consumption, regular exercise, and avoidance of constipating medications, should help prevent future problems. Recommend surgical referral for symptomatic hemorrhoids, because a variety of procedures (sclerosing injections, rubberband ligation, photocoagulation, cryotherapy, electrocautery, laser treatments, radiofrequency ablation, staple repair, or excision) can provide definitive treatment. A rare complication of hemorrhoidal banding is pelvic sepsis.2 Obtain surgical evaluation in the ED for continued and severe bleeding, pain, incarceration, and/or strangulation (grade IV internal hemorrhoids). External hemorrhoidal thrombosis is usually self-limiting, with resolution in 1 week. Therapy for thrombosed external hemorrhoids depends on the severity of symptoms. If the thrombosis has been present for more than 48 hours, the swelling has started to shrink, the hemorrhoid is not tense, and the pain is tolerable, the patient may be treated with warm baths and bulk laxatives. Suppositories, which are placed proximal to the anorectal ring, are of no help. If, on the other hand, the thrombosis is acute, has lasted less than 48 hours, and is extremely painful, significant relief can be provided by clot excision.

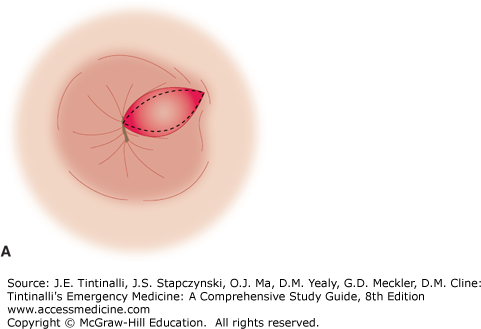

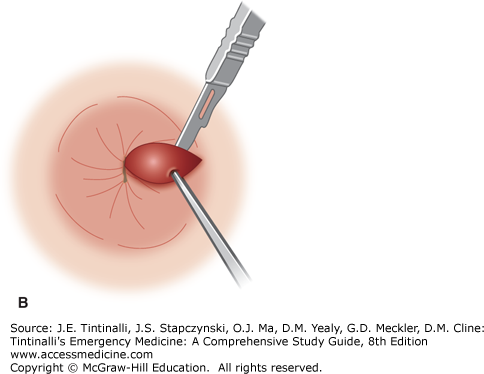

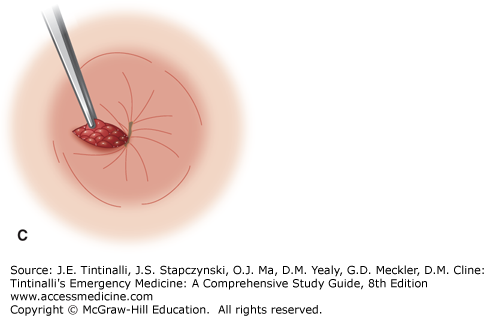

Excision of thrombosed external hemorrhoids should not be performed in the ED on immunocompromised patients, children, pregnant women, patients with portal hypertension, and those who are anticoagulated or have a coagulopathy. Obtain optimal exposure by placing the patient in the side-lying or prone position. The area of the overlying skin to be incised is infiltrated using a 30-gauge needle with a local anesthetic such as bupivacaine 0.5%, with epinephrine (1:200,000), and bicarbonate buffering. An elliptical incision distal to the anal verge in the overlying skin will expose the thrombosis. Remove the clot through the incision site. Because multiloculated clots can be present, the technique of unroofing a thrombosed hemorrhoid with an elliptical incision and removing the overlying skin gives far better results than the simple incision and evacuation of a clot (Figure 85-9, A–C).

Control the bleeding by tucking the corner of a small piece of gauze into the wound and leaving it in place for a few hours. A small pressure dressing may be applied external to the gauze and removed when the patient takes the first warm bath in 6 to 12 hours. Narcotics may be prescribed, but they cause constipation and may produce more problems. Complications, such as continued bleeding, recurrence, infection, fistula, and abscess formation, may occur; thus follow-up in 24 to 48 hours is recommended. Referral for definitive hemorrhoidectomy is prudent. Recently, small studies suggest that patients with acutely thrombosed internal or external hemorrhoids can be treated with topical nifedipine and 1.5% lidocaine ointment or isosorbide dinitrate ointment with surgical follow-up.2,3

ANAL FISSURES

An anal fissure is the result of a superficial linear tear of the anal canal below the dentate line and extending distally to the anal verge (Figure 85-10). Acute fissures are present for less than 6 weeks; fissures are chronic if they persist longer. The mucosa of the anal canal has a rich supply of somatic sensory nerve fibers. Chronic anal fissures are pale in color with edema of the surrounding tissues. Fissures persist because of the severe, chronic, internal sphincter spasm that may occur along with development of a secondary infection at its base. The fissure edges become fibrotic and raised, possibly exposing sphincter fibers, hypertrophic papillae proximally, and the characteristic sentinel tag distally. The latter is frequently misdiagnosed as an external hemorrhoid when, in actuality, it is the result of edema and fibrosis secondary to the ulcerating fissure. The fissure may become inflamed and form a perianal or intersphincteric abscess that may drain into the anal canal or in the posterior midline externally.

FIGURE 85-10.

Anal mucosal fissures. A. Constipation. B. Sexual assault. [A: Photo contributor: Paul J. Kovalcik, MD. Reproduced with permission from Knoop K, Stack L, Storrow A, Thurman RJ: Atlas of Emergency Medicine, 3rd ed. © 2010, McGraw-Hill, New York. Figure 9-32; B: Reproduced with permission from Knoop K, Stack L, Storrow A, Thurman RJ: Atlas of Emergency Medicine, 3rd ed. © 2010, McGraw-Hill, New York.]

Anal fissures are usually single and occur in the midline posteriorly in 80% to 90% of cases.4 The posterior location of anal fissures may be because of the posterior angulation of the rectum on the anus where the posterior midline of the anorectal canal becomes the “lesser curvature” for the passage of stool. Anterior anal fissures are associated with younger age (33 years versus 41 years for posterior fissures), female sex, obstetric trauma, and occult external anal sphincter injury.5 A chronic nonhealing fissure, lasting more than 6 weeks, or one not located in the midline should arouse suspicion that another, potentially serious cause may be involved. Such diagnostic possibilities include Crohn’s disease, chronic ulcerative colitis, squamous cell carcinoma of the anus, adenocarcinoma of the rectum invading the anal canal, localized anal cancers such as Bowen’s disease and extramammary Paget’s disease, leukemia, lymphoma, syphilitic fissures, chlamydia, gonorrhea, human immunodeficiency virus, and a tuberculous ulcer. Consideration of these diagnoses requires referral for diagnostic biopsy of the ulcer edge, culture of the anal canal, and a systemic evaluation. Fissures due to Crohn’s disease are multiple, off midline, and asymptomatic more commonly than the general population.6 Most often, the traditional midline anal fissure is caused by the trauma produced by the passage of a particularly hard and large fecal mass, but it also may be seen after frequent acute episodes of diarrhea. Children with constipation will commonly complain of painful defecation only to find an anal fissure upon closer inspection (Figure 85-10A). Child abuse should be considered as a possible cause (Figure 85-10B).

Anal fissures are characterized by tearing pain with defecation and rectal bleeding. The pain may persist as a dull ache and burning sensation for a few hours after each bowel movement. Invariably it subsides between movements, which is a feature that distinguishes fissures from other forms of painful anorectal disease. The bleeding is bright red and small in quantity, usually being noticed only on the toilet paper. In infants, the presence of small amounts of bright red blood on the stool or toilet paper is usually the presenting complaint from an anal fissure. Sphincter spasm and pain may be severe enough to make the patient retain stool and avoid defecation. The diagnosis of an anal fissure is usually suggested by the history, but the anal area must be examined in all cases. Fissures may often become more noticeable if the patient bears down as if having a bowel movement. With the patient relaxed, gentle separation of the buttocks will often expose the fissure. The mere retraction of the buttocks and the anal skin may cause considerable spasm and discomfort and may not permit digital examination. Topical 2% lidocaine jelly may provide some relief for examination, but severe pain may require sedation. If the fissure can be visualized and is present in the posterior midline, rectal examination can be deferred until the patient is having less spasm and pain.

Healing is by the development of granulation tissue and the re-epithelialization of the ulcerated area. Most uncomplicated acute fissures will heal in a few weeks, but relapse can be as high as 50%. If healing does not occur within 6 weeks or relapses are frequent, surgical referral is recommended. Treatment is aimed at providing symptomatic relief, extinguishing the anal sphincter spasm, and preventing stricture formation. Warm baths for at least 15 minutes three to four times a day and after each bowel movement along with stool softeners may suffice. The addition of fiber to the diet will serve to prevent stricture formation by providing a bulky stool. Warm baths and increased fiber will result in healing in about half of all anal fissures.6 Topical lidocaine ointments and 1% hydrocortisone creams may provide symptomatic relief. Medical therapies for anal fissure are generally no more effective than placebo, and for chronic fissures, all medical therapies are less effective than surgery.7,8

ANAL STENOSIS

Anal stenosis occurs when the pliable tissue is replaced by scarred fibrotic tissue. Congenital and primary causes may occur, yet secondary causes are more common. Stenosis most commonly occurs after surgical hemorrhoidectomy.4 Other causes include radiation, fistulectomy, trauma, inflammatory bowel disease, chronic laxative use, sexually transmitted diseases, and chronic diarrhea.

Typical complaints include constipation, bleeding, pain with stool evacuation, and narrow-caliber stools. As stenosis progresses, performing a digital exam with the little finger is met with severe resistance. Incontinence secondary to overflow constipation may occur. Careful specialist examination, often with sedation, may be necessary.

Treatment involves stool softeners, fiber supplementation, and daily gradual anal dilatation after initial dilatation in the operating room. Stricturotomy and stricturoplasty are used when conservative management has failed.

CRYPTITIS

Anal crypts are superficial mucosal pockets that lie between the columns of Morgagni. Formed by the puckering action of the sphincter muscles, crypts normally flatten out during the passage of a stool. Sphincter spasm and superficial trauma caused by repeated bouts of diarrhea or chronic constipation may cause breakdown in the mucosal lining of the crypts, leading to cryptitis. Infecting organisms enter crypt pockets, and inflammation extends into the lymphoid tissue of both the crypts and anal glands. Cryptitis could well be the common denominator for the development of fissure-in-ano, fistula-in-ano, and perirectal abscesses (Figure 85-11, A and B).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree