INTRODUCTION

An aneurysm is dilation of the arterial wall to >1.5 times its normal diameter. Aneurysms have been classically distinguished as true aneurysms, pseudoaneurysms, and mycotic aneurysms. The wall of a true aneurysm involves of all layers of the vessel. Risk factors for these include connective tissue disorders, familial history of aneurysm, and atherosclerotic risk factors (i.e., age, smoking, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia). A progressive decrease in elastin, collagen, and fibrolamellar units results in thinning of the media of the vascular wall and a decrease in its tensile strength. In aortic true aneurysm, the dilatation and increased wall force are intertwined, creating more dilatation (Laplace law: wall tension = pressure × radius). The rate of aneurysmal dilatation is variable and predictable, with larger aneurysms expanding more quickly and changing a mean 0.25 to 0.5 cm per year. However, abrupt expansion occurs and is not predictable, with larger aneurysm more likely to rupture. Rupture is catastrophic, occurring once the stress on the vessel wall exceeds its tensile strength.

The wall of a pseudoaneurysm consists partly of the vessel wall and partly of fibrous or other surrounding tissue. A pseudoaneurysm can develop at the site of previous vessel catheterization and at anastomoses from prior vascular reconstruction, trauma, or infection.1 Small pseudoaneurysms may eventually spontaneously thrombose.

A mycotic aneurysm develops as a result of infection in the vessel wall, often in an immunocompromised patient. The source can be direct extension from a neighboring infection or embolization from valvular endocarditis.

Peripheral and visceral aneurysms are less frequent but an important subset of arterial aneurysmal disease. Popliteal artery aneurysms are the most common peripheral aneurysm; they often co-exist with contralateral popliteal aneurysms or abdominal aortic aneurysms.2 Aneurysms of the femoral artery are uncommon and often accompany aneurysmal disease at other sites. Visceral artery aneurysms may occur anywhere but are most common in the renal, splenic, and hepatic arteries. Most visceral aneurysms remain silent and undetected until a complication such as rupture occurs. All but splenic artery aneurysms are more common in elderly men. Complications of aneurysms include rupture, which has an 80% mortality rate,3 and thrombosis, creating ischemia in the perfused organ.4,5

GENERAL CLINICAL FEATURES OF ANEURYSMS

Clinical signs and symptoms can be nonspecific; often, the symptoms are driven by location, the pressure exerted upon neighboring structures, or the signs of peripheral embolization from an intramural thrombus. Visceral aneurysms are often detected after an abdominal CT scan for abdominal or flank complaints; similarly, lower extremity aneurysms are often detected during an extremity Doppler US examination in a search for deep venous thrombosis. Once rupture occurs in any truncal aneurysm, hemorrhagic shock develops and mortality is high without prompt surgical intervention.

SYMPTOMATIC ABDOMINAL AORTIC ANEURYSMS

An abdominal aortic aneurysm is defined as an aorta ≥3.0 cm in diameter; repair is considered for an aneurysm ≥5.0 cm in diameter. Patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm often (18%) have a first-degree relative with an aortic aneurysm, compared with <3% of those without aneurysm. Most patients are >60 years old, and males have an increased risk of the disease. Patients with aneurysms involving other major arteries and those with peripheral arterial disease are also at increased risk for aortic aneurysmal disease. The risk increases with the number of years of smoking and decreases with the number of years since quitting smoking.6 As smoking becomes less prevalent in the United States, abdominal aortic aneurysm deaths have decreased.7

Symptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysms may present with a variety of signs or symptoms that can mimic other primary diagnoses: syncope; flank, back, or abdominal pain; GI bleeding from an aortoduodenal fistula; extremity ischemia from embolization of a thrombus in the aneurysm; shock; or sudden death. Sudden death most commonly occurs from intraperitoneal rupture of the aneurysm, which leads to massive, rapid blood loss. Syncope without warning symptoms followed by severe abdominal or back pain suggests rupture of an abdominal aortic or visceral aneurysm with some temporary containment. Syncope is caused by rapid blood loss and a lack of cerebral perfusion. Patients may regain consciousness, but irreversible hemorrhagic shock follows without prompt diagnosis and intervention.

Back or abdominal pain is the most common presenting symptom with aortic aneurysm or rupture. The pain is classically severe and abrupt in onset, with about half of patients describing a ripping or tearing pain. Syncope occurs in about 10%. Many patients present with nonclassic sites of pain: flank, groin, isolated quadrants of the abdomen, and hip. Other common symptoms exist, such as nausea, vomiting, bladder pain, hip pain, or tenesmus.

Physical examination has only a moderate ability to detect a large abdominal aortic aneurysm. The sensitivity of abdominal palpation increases with aortic aneurysm diameter, ranging from 29% for a diameter of 3.0 to 3.9 cm to 50% for a diameter of 4.0 to 4.9 cm and 76% for a diameter of ≥5.0 cm.8 Tenderness to palpation of an aneurysm is commonly interpreted as a sign of aneurysmal expansion or rupture. However, a lack of tenderness does not indicate an intact aorta. Examination is difficult in the obese and the very thin.

The differential diagnoses include the causes of syncope, abdominal pain, chest pain, back pain, and shock. When seeing patient with abrupt back pain with syncope or shock, consider aortic aneurysm rupture. However, other cardiac, abdominal, and retroperitoneal diseases may be the cause, including renal disorders, hepatobiliary disorders, and pancreatic disease. If symptoms are insidious, it is possible that some patients may appear well enough and receive benign diagnoses, such as musculoskeletal back pain, and are discharged from the ED.

Diagnosis is confounded by coexisting pathology. Coronary artery disease and chronic lung disease are often present, and signs and symptoms of these disorders may distract the physician from the diagnosis of aneurysmal disease. This is especially true in patients without severe pain or with findings that seem congruent with another cause (e.g., ECG changes or dyspnea).

External signs of acute rupture are rare and include periumbilical ecchymosis (Cullen sign) or flank ecchymosis (Grey Turner sign). Retroperitoneal blood may dissect into the perineum or groin, causing scrotal or vulvar hematomas, or inguinal masses. Retroperitoneal blood may irritate the psoas muscle, triggering an “iliopsoas sign” (pain upon extension of the hip, typically with the patient lying on the opposite side). Blood may compress the femoral nerve and present as a neuropathy. The presence or rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm typically does not alter femoral arterial pulsations.9

Think of aortoenteric fistulas in patients with unexplained or high-volume upper or lower GI bleeding, especially in patients without liver disease. A history of aortic graft placement increases the risk of fistula. Fistulas most frequently involve the duodenum, with hematemesis, melenemesis, melena, or hematochezia. While massive, life-threatening bleeding is common, mild sentinel bleeding may be the first sign. Aortic aneurysms also may erode into the venous vasculature and form aortovenous fistulas, which cause high-output cardiac failure, decreased arterial blood flow distal to the fistula, and increased central venous volume.

Contained chronic abdominal aortic aneurysmal ruptures are not common. A retroperitoneal rupture may cause enough fibrosis to limit blood loss, and the patient may look well. The inflammatory response commonly causes pain, with pain continuing for an extended interval, clouding the diagnosis.

Imaging performed away from the bedside can delay emergency consultation and operative repair, so consult a surgeon early and before any transport for imaging when a symptomatic aneurysm is suspected.

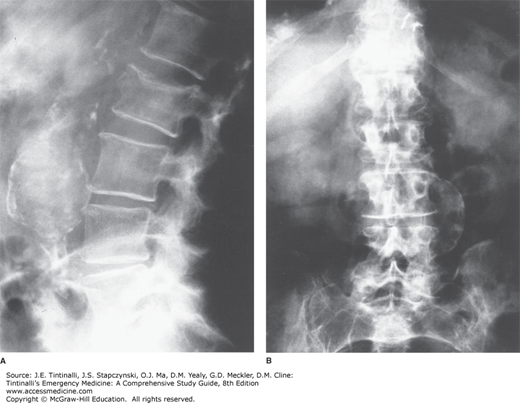

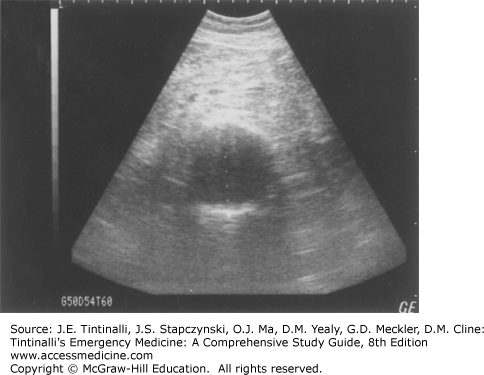

Radiologic evaluation may include plain radiography (Figure 60-1), US (Figure 60-2), CT scanning (Figure 60-3), or MRI. Plain abdominal films may show a calcified and bulging aortic contour, implying the presence of an aneurysm (Figure 60-1). Approximately 65% of patients with symptomatic aortic aneurysmal disease have a calcified aorta, often better seen on a lateral view. An anteroposterior projection may show an arch of calcification, most commonly on the patient’s left. Rarely, a chronic aneurysm may erode into a vertebral body and be seen on plain film. Plain film radiographs do not exclude the presence of abdominal aortic aneurysm or detect rupture and can be omitted in most patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree