CLINICAL PEARLMultiple gestation delivery is high risk, associated with CD, preterm birth, and obstetric conditions such as preeclampsia.

II.National Guidelines

These U.S. guidelines present practice recommendations related to current evidence for multiple gestation, anesthetic management, and pharmacologic therapies. The pertinent topics in these guidelines are summarized and further expanded throughout this chapter.

A. Practice guidelines for obstetric anesthesia: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Obstetric Anesthesia.7 These American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) 2007 guidelines, updated from 1998, refer to management of anesthesia for multiple gestation pregnancy labor and delivery.

1. Platelet count. Maternal anesthetic complications, such as neuraxial hematoma, may be reduced by checking a platelet count prior to placement of epidural anesthesia in patients with preeclampsia. A routine platelet count will not reduce complications associated with neuraxial block placement. However, a low platelet count seen in hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets (HELLP) syndrome, a variant of preeclampsia, is more common in multiple gestation pregnancies.

2. Early epidural placement. This is recommended for multiple gestation and for preeclampsia. The potential for CD and to avoid unplanned general anesthesia are the reasons behind this plan. Placement of labor epidural catheters should be encouraged before labor or in early labor.

B. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2014 Practice Bulletin 144: multiple gestation—complicated twin, triplet, and high-order multifetal pregnancy.8 This 2014 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Practice Bulletin, updated from 2004, acknowledges a rise in multiple gestation pregnancies. The increase is attributed to advanced maternal age (associated with spontaneous multiple gestation pregnancy) and assisted reproductive technology.

C. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2013 Committee Opinion 560: medically indicated late-preterm and early-term deliveries.9 This document summarizes recommended delivery timing for twin pregnancies, dependent on concurrent obstetric conditions (see Section V.B. in the following text).

D. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2013 Committee Opinion 573: magnesium sulfate use in obstetrics10

1. Magnesium administration for fetal neuroprotection is indicated if delivery is anticipated before 32 weeks gestational age.

2. Women may receive magnesium sulfate for up to 48 hours during the period of antenatal corticosteroid administration, if they are between 24 and 34 weeks’ gestation and at risk for preterm delivery within 7 days.

III.Maternal adaptation to multiple gestation pregnancy

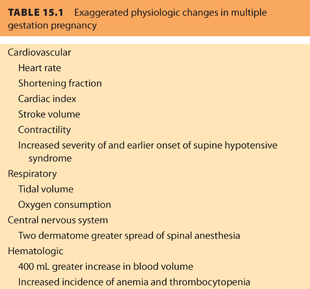

The wide-ranging maternal physiologic adaptations of pregnancy are presented in Chapter 1. Multiple gestation pregnancy exaggerates many of these changes, with implications for anesthetic management and maternal safety (see Table 15.1).

A. Cardiovascular system

Many of the cardiovascular changes associated with singleton pregnancy have been described in the past decade using echocardiography. Cardiac output increases with gestational age along with stroke volume; these changes are more dramatic than with singleton pregnancy. Cardiac output is 20% greater—a consequence of exaggerated responses of stroke volume and heart rate.11 Preload is further increased above singleton pregnancy after 20 weeks. Aortocaval compression, seen from 20 weeks in singleton pregnancy, is exaggerated in twin pregnancy and may present earlier.12,13 Preeclampsia is more common in multiple gestations pregnancies.11,14 Gestational hypertension presenting during twin pregnancy progresses more frequently to preeclampsia than in singleton pregnancy.15

B. Respiratory system

The greater abdominal size with multiple gestation pregnancies compounds respiratory changes and may cause dyspnea.16 However, respiratory function does not appear to differ markedly compared to singleton pregnancies.17 Nevertheless, the enlarged abdomen and elevated serum progesterone levels may impact respiration in multiple gestation pregnancy.18

C. Central nervous system

The mechanism for enhanced effect of spinal drug in multiple gestation pregnancy may be related to aortocaval compression.12 Spinal anesthesia drug spread is greater compared to singleton pregnancy and is reportedly two dermatomes higher. Another explanation relates to higher cerebrospinal fluid progesterone levels that contribute to a neural sensitizing effect with lower doses achieving a denser block.19 Hemodynamic instability after spinal anesthesia is not greater in multiple gestation pregnancies, as expressed by vasopressor requirements during CD.20 Spinal anesthesia has been reported to be safe in triplet21 and quadruplet pregnancies.22

D. Hematologic changes

Blood volumes increase more in twin pregnancy compared with singletons.23 Morbidity and mortality are increased in multiple gestation pregnancy and in an advanced age population.24 Aside from thrombocytopenia associated with HELLP syndrome, multiple gestation pregnancies frequently feature gestational thrombocytopenia. Morikawa et al.25 reported a count below 100,000 in 43% of triplet pregnancies compared with 4.3% for twin pregnancy. Triplet pregnancies are associated with further increased risk for HELLP and acute fatty liver disease compared with twin pregnancies. Regarding platelet counts that may impact neuraxial anesthesia, 3.2% of women carrying triplets had platelet counts <70,000 per mcL,26 and thrombocytopenia frequently preceded the diagnosis of preeclampsia.

IV.Obstetric conditions and concerns for multiple gestation pregnancy

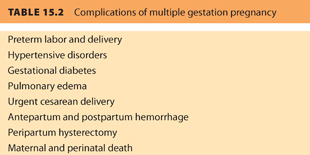

Complications of multiple gestation pregnancy are listed in Table 15.2.

A. Preeclampsia

Hypertension is more frequent in twin pregnancy than singletons. In a perinatal database case-control study from 1982 to 1987, the likelihood of hypertension was 2.5 times higher among 1,253 twin versus 5,119 singleton pregnancies (odds ratio [OR], 2.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.1 to 3.1).6 Preeclampsia may be more prevalent in multiple gestation pregnancies. Foo et al.15 reported that multiple gestation pregnancies with de novo hypertensive disorders were more likely to progress to preeclampsia than singletons (24 per 70 [34%] vs. 279 per 1,881 [15%], P < .001). A similar finding was reported for progression of chronic hypertension to preeclampsia in twins (53%) versus singletons (18%), P < .01. The initial hypertensive-related disorder diagnosed in twin pregnancies was more likely to be preeclampsia rather than gestational hypertension.

B. Maternal hemorrhage

1. Multiple gestation pregnancy has a greater blood loss (>900 mL)—similar to that seen in CD and double that seen following singleton delivery.23 Placental abruption is three times more likely among twin pregnancies compared with singletons (OR, 3.0; 95% CI, 1.9 to 4.7) and the frequency is more apparent after adjustment for maternal age and weight gain (OR, 3.7; 95% CI, 2.6 to 3.5).6

2. The rate of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is doubled in multiple gestation pregnancies and occurs in approximately 9% of deliveries, in part due to the increased abruption rate.27 The distended uterus may also become atonic. Independent risk factors for PPH in twin pregnancies were reported in a 9-year Japanese cohort. When the gestational age was >41 weeks, the risk of PPH was over 8 times more likely compared to a singleton pregnancy. Hypertensive disorders were over 5 times more likely to be associated with PPH.28

3. PPH protocols can guide management of this potentially life-threatening event. PPH should be anticipated in multiple gestation deliveries.29 Airway considerations, readily available equipment (e.g., intravenous [IV] access, rapid infusers, warming blankets), massive transfusion protocols, uterotonics (e.g., oxytocin, Methergine, misoprostol, and Hemabate), and regular protocol drills are all important.30,31

CLINICAL PEARLMany centers use strategies such as massive transfusion protocols (MTPs) to efficiently manage transfusion for PPH. Practice drills may improve the implementation of these MTPs and other institution-specific strategies. Visual aids placed in the labor and delivery suites may act as reminders for the PPH algorithm when massive hemorrhage occurs.

C. Fetal surgery. Monochorionic twins comprise 20% of twin pregnancies,32 and up to 20% of these will develop twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS). Recent advances in management of TTTS make it likely that fetoscopic laser therapy may be performed. One potential maternal complication of TTTS is “mirror syndrome” causing maternal hydrops with edema, oliguria, and hemodilution.33 Mirror syndrome may be mistaken for preeclampsia, but the presence of fetal hydrops may direct the diagnosis. Management of the mother with mirror syndrome includes consideration of her volume status, cardiovascular function, and use of appropriate hemodynamic monitoring; neuraxial anesthesia is a suitable option. However, general anesthesia may be necessary and airway edema may increase the risk of difficult airway management.34 Traditionally, fetal surgery for TTTS was performed 17 to 26 weeks’ gestation. However, recent data suggest that fetoscopic surgery may be performed in the third trimester, with good fetal survival and rates of maternal complications (e.g., intensive care unit [ICU] admission, pulmonary edema, mirror syndrome, hemorrhage requiring transfusion) similar to earlier procedures.35 Maternal outcomes for fetal surgery are not widely reported. Among 53 fetal procedures performed for cardiac indications, 1 unrelated PPH occurred. However, maternal morbidity (e.g., anesthesia complications such as aspiration, anaphylaxis, cardiovascular complications, airway injuries, awareness, or hypoxic injury) was absent.36 Fetal reduction may be performed early in pregnancy to reduce the incidence of preterm birth. Fetal reduction may also attenuate obstetric-related conditions, such as gestational hypertension.37

CLINICAL PEARLFetal surgery is not performed at all institutions. However, because more centers are introducing fetal surgery, special training and multidisciplinary protocols may be required for institution-specific anesthetic strategies.

D. Maternal morbidity. There is an increased incidence of concurrent medical and obstetric conditions. Anemia, hemorrhage, hypertension, and preeclampsia are more common in multiple gestation pregnancies. The precipitous rise in multiple gestation pregnancy, in particular among women of advanced age,23 contributes to the recent observation of rising maternal mortality. Multiple gestation pregnancies are associated with a mortality risk ratio of 3.6 (95% CI, 3.1 to 4.1) compared to singleton pregnancies.38 Specific conditions such as thromboembolism, hemorrhage, and hypertensive disease are associated with multiple gestation pregnancy.39 African American twin and high-order multiple pregnancies have a higher incidence of death compared to whites.39

CLINICAL PEARLMultiple gestation pregnancies and associated maternal morbidities are contributing to the rising rate of maternal mortality. Women with multiple gestation pregnancy should be closely monitored and cared for by a multidisciplinary team, and morbidities should be anticipated.

E. Other concerns. Multiple gestation pregnancy is more likely than singleton pregnancy to be delivered by CD. Multiple gestation may be associated with postpartum depression.

V.Timing of delivery for multiple gestation pregnancy

A. Overview

Multiple gestation pregnancies are associated with maternal morbidity, neonatal morbidity, and prematurity, all of which may be difficult to prevent. Multiple gestation pregnancies deliver earlier than singletons, and twin gestation pregnancy lasts, on average, 35 weeks.40 Birth weights are smaller for twin pregnancies6 and one study suggests better outcomes when elective twin delivery is performed at 37 weeks rather than expectant care (from 38 weeks to later).41 The majority of twin pregnancies will deliver before 37 weeks. Among 138,660 twin births reported in one survey, almost 60% were delivered before the 37th week.40

B. Medically indicated delivery timing. Uncomplicated dichorionic-diamniotic twins can be delivered at 37 to 38 weeks’ gestation.42 ACOG recommends delivery in the 38th week in uncomplicated dichorionic-diamniotic twin pregnancy.9 Earlier delivery has been recommended for monochorionic-diamniotic twins (34 to 37 weeks)9,42 and many US practitioners deliver monoamniotic-monochorionic twins by 34 weeks because of the risk of perinatal morbidity and mortality.43

C. Preventing multiple gestation preterm birth. There are no currently effective treatments to avoid preterm delivery in multiple gestations pregnancies. 17-α hydroxyprogesterone caproate44 and vaginal progesterone45 do not prevent preterm twin birth. Cerclage may be harmful.46

VI.Preterm birth in multiple gestation pregnancy

A. Predicting preterm birth. Cervical length, fetal fibronectin, home uterine monitoring, and digital examination are modalities used to predict preterm birth. However, these modalities are not recommended for asymptomatic multiple gestation because they do not prevent spontaneous preterm birth. Even for symptomatic multiple gestation, their use is not exclusively recommended.

B. Interventions to prevent preterm birth, such as cerclage, bedrest, and prophylactic tocolytics, are not recommended in multiple gestation because they fail to prevent preterm birth. 17α-Hydroxyprogesterone caproate may increase multiple gestation midtrimester fetal loss and is not associated with reductions in maternal morbidity.

C. Pharmacologic therapies to prevent preterm birth may be combined with corticosteroids.

1. Corticosteroids may not be beneficial in multiple gestation pregnancies at risk for preterm birth. Expert opinion recommends the administration of a single course of corticosteroid between 24 and 34 weeks’ gestation in singleton pregnancies, when the pregnancy is at risk for preterm delivery within 7 days.47

2. Tocolytics to prevent uterine contractions (β-agonists such as ritodrine, terbutaline, or calcium channel blockers) may cause maternal tachycardia, hypotension, and electrolyte abnormalities, such as hyperglycemia and hyperkalemia. Combination therapies may be used despite a paucity of evidence for maternal or neonatal advantage.48 Pulmonary edema may result from tocolytic therapy. One therapy to consider is epidural anesthesia to relieve cardiac efforts associated with this condition.49

3. Magnesium therapy. Recent evidence from preeclampsia studies showed magnesium sulfate therapy generates a fetal neuroprotective effect for preterm birth up to 32 weeks.47 Magnesium has not been proven to be as beneficial as it has for singleton pregnancies; however, its use is recommended for multiple gestation pregnancies. Magnesium sulfate administration for up to 48 hours prior to preterm labor may have maternal consequences. Although there were no serious maternal adverse effects (e.g., death, cardiac arrest, respiratory arrest) reported in the IRIS trial, arm discomfort and warmth over the body were reported in over two-thirds of the women receiving magnesium for fetal neuroprotection in the first hour regardless of the loading time (20 minutes vs. 1 hour).50 The use of magnesium for neonatal neuroprotection or seizure prophylaxis can prolong maternal neuromuscular blockade.

D. Anesthesia for multiple gestation preterm birth. CD is more likely in preterm delivery of multiple gestation. Anesthesia modes for preterm birth delivery are not frequently reported but neuraxial techniques are most frequently employed in most centers. Epidural analgesia can optimize vaginal delivery conditions for the premature neonate, moderated through pelvic floor relaxation, which may reduce maternal expulsive efforts.51

VII.Delivery route for multiple gestation pregnancy

A. Overview. The decision for twin delivery route is based on fetal lie, ability to monitor the fetus through labor, and maternal–fetal well-being, according to the ACOG Practice Bulletin.8 Multiple gestation is associated with an increased incidence of fetal malpresentation and congenital anomalies. These conditions may impact delivery choice.52

B. Delivery route. Vaginal birth is suitable for vertex-presenting twin pregnancy. Non-twin multiple gestation pregnancies will be delivered by CD. Monoamniotic twins are often delivered by CD because of the risk of perinatal mortality.

C. Cephalic-cephalic presenting twins have the best chance of vaginal delivery (and comprise 40% of twin deliveries).53 The likelihood of CD is 6.3%; the likelihood of operative vaginal delivery is 8.3% following successful cephalic primary twin delivery.54 CD may be the necessary delivery option for the second twin in an emergency, for example, fetal distress and cord prolapse.54 Neonatal morbidity for the second twin is highest after failed vaginal delivery. If it is likely that the second twin will fail to delivery vaginally, CD for both twins is the best delivery route.55

D. Cephalic-noncephalic presenting twin have a high chance of successful vaginal delivery after version of the noncephalic second twin, although the most likely reason for CD is malpresentation.56 A randomized controlled trial (RCT) of vaginal versus planned CD for 2,800 twin gestations (vertex-presenting twin), between 32 and 38 weeks’ gestation, demonstrated similar outcomes for severe maternal and neonatal morbidity, regardless of delivery mode.57 The incidence of the primary outcome (i.e., a neonatal morbidity composite) was similar for planned CD versus vaginal delivery (2.2% vs. 1.9%, respectively; OR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.77 to 1.74), thus supporting the practice of vaginal delivery for twin pregnancies with cephalic-presenting fetus.

VIII.Anesthesia for vaginal delivery in multiple gestation pregnancy

A. Labor patterns are prolonged compared with singletons,58 and epidural use for twin delivery may improve maternal relaxation to avoid premature pushing, enable breech extraction, and can be extended if operative vaginal or CD is required.51

B. Unplanned operative delivery. Due to the potential for unplanned operative delivery in twins attempting vaginal delivery, there is debate surrounding the optimal location for twin delivery. Limited resources and logistics may limit the routine availability for an operating room for vaginal twin delivery. On the other hand, need for rapid delivery conditions may make operating room delivery safer. In addition, the mandatory presence of the anesthesia provider during twin delivery may be beneficial to ensure adequate labor analgesic levels, uterine relaxation for fetal manipulation such as internal podalic version, or provide rapid surgical anesthesia.51 Carvalho et al.51 surveyed California hospitals regarding practice for twin delivery and there was no consensus: 64% perform vaginal twin delivery in the operating room, 55% provide an anesthesiologist during the delivery, and a strong association exists between these two factors. Conversely, there was no association between hospital characteristics (type, location, delivery rate) and the delivery location.

CLINICAL PEARLThere is no specific recommendation that twins should be delivered in the operating suite or that anesthesia providers should be present at the delivery. For anesthesia personnel attending a twin delivery, preparations for emergency transfer to the operating room and emergency CD considerations may be required. Although there is a valid argument supporting vaginal twin delivery in the operating room, there may be logistic limitations such as operating room availability.

IX.Anesthesia for cesarean delivery in multiple gestation pregnancy

A. Cesarean delivery for multiple gestation is frequently performed. In a study of 12 Finnish delivery units, multiple gestation was the cause of up to 80% of CD.59 Based on current guidelines from the ASA, a neuraxial anesthesia technique is the recommended route for women undergoing CD.60 Rates of anesthesia-related maternal morbidity have decreased, concurrent with a rise in neuraxial anesthesia use for CD.61,62 Left lateral tilt should be used as in all pregnancies because aortocaval compression following neuraxial anesthesia is more exaggerated in multiple gestation pregnancy.18

B. Unplanned cesarean delivery (vertex second twin) may be associated with emergency indications, such as cord prolapse and fetal bradycardia, both necessitating rapid surgical intervention.54 CD is preferentially chosen over vaginal operative delivery for a second vertex twin delivery in cephalopelvic disproportion, fetal bradycardia, and cord prolapse. Ideally, an epidural catheter placed for twin delivery can be extended to provide suitable and timely surgical conditions. However, epidural failure or urgent surgery may necessitate general anesthesia.63,64 Complications from general anesthesia, such as aspiration and airway management disasters, can be avoided by using a neuraxial technique.65

CLINICAL PEARLCD is preferentially chosen over vaginal operative delivery for second vertex twin delivery in cephalopelvic disproportion, fetal bradycardia, and cord prolapse.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree