Chapter 12 Anesthesia and Perioperative Safety

Safety is the most important consideration in anesthesia care. The risk for death associated with anesthesia care has diminished greatly during the past 50 years. In To Err Is Human, the landmark publication that ignited the twenty-first century health care safety revolution, the authors specifically recognize the pioneering role of anesthesiology in advancing patient safety by a dedicated and consistent professional action program (Kohn et al, 2000).

Although each team member in perioperative care has specific profession-related goals, everyone is also invested in the anesthesia provider’s patient commitments: maintenance of airway, breathing, circulation, and other physiologic parameters; provision of analgesia, sleep, and amnesia; and optimizing anatomic and physiologic conditions for the surgeon’s work. Safety issues become more complicated by factors such as individual patient variability, complex medical and surgical conditions, defined institutional processes, and anesthesia-unique complications. Orkin and Longnecker (2008) relate about 75% of risk to patient-specific characteristics, including age, gender, and comorbidities; surgical issues account for 20% of risk; and 5% of risk is assigned directly to anesthesia-related factors.

With shared commitment to safety, everyone in the operating room (OR) is a member of the anesthesia care team. Complete safe care of the surgical patient cannot be separated from the anesthesia care. Anesthesia providers rely on other team members to help prevent certain complications and to assist with treatment of others. Knowledge about selected anesthesia complications and ongoing communication with anesthesia providers are essential components of perioperative safety. The different vantage point of perioperative nurses in the surgical environment, as well as sharply honed nursing skills and professional intuition (Benner and Tanner, 1987; Rovithis and Parissopoulos, 2005), also link them to the anesthesia team as communicators, patient advocates, resource providers, and hands-on colleagues.

Anesthesia care always has potential for disaster. Anesthesia providers deliver potent medications, interfere with breathing, alter physiology, and perform invasive procedures, often on patients with serious underlying medical and surgical problems, using sophisticated equipment and supplies. There is little or no margin of error. Quick intervention may be necessary, sometimes to the point of full resuscitative efforts. Vital sign changes, airway problems, major bleeding, or other serious intraoperative events sometimes require skilled assistance from other perioperative team members. Although the most serious anesthesia complications are very rare, it is important for the entire team to be prepared for them, just as airline, submarine, and space crews prepare for disasters. The goal of anesthesia care must be to ensure that no patient is harmed (Cooper and Longnecker, 2008). We must constantly remind ourselves that as anesthesia safety has improved during past decades, complacency and overconfidence are frequently our companions. Consider the analogy of Captain “Sully” Sullenberger’s safe landing of a large airliner on the Hudson River on January 16, 2009, with no loss of life to 155 passengers, after a bird strike caused complete engine failure (McFadden, 2009). Only a truly well-prepared team with disaster training and a strong leader could manage such a dramatic event. Like Captain Sullenberger and his crew, the perioperative team must be fully prepared for disasters we hope not to experience.

TYPES OF ANESTHESIA

General Anesthesia

Induction and Emergence

In this emergence period, perioperative nurses are also taxed with end-of-case responsibilities, yet first allegiance to patient safety requires presence and engagement during the emergence process. Besides increasing safety, participation with anesthesia providers during the most critical parts of anesthesia care increases the ability of perioperative nurses to provide meaningful reports to the next registered nurse (RN) in the PACU or the intensive care unit. A structured communication tool such as the SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendation) report developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (2009) and adapted by others allows coherent organization of the information to be transmitted. Although anesthesia providers deliver the full anesthesia care report, the perioperative nurse’s responsibility for the whole patient should include a brief description of the anesthetic course, especially if there were untoward events or crises. Reports that focus only on surgical drains, dressings, and names of procedures diminish the role of the perioperative nurse as a professional participant in whole-patient care. Communication and interaction among the anesthesia provider, surgeon, and perioperative nurse during events of the procedure are then summarized at the end-of-procedure sign-out, as recommended by safety groups such as the World Health Organization (2008).

Safety and General Anesthesia

Airway Problems

However, despite best efforts, complete inability to oxygenate and ventilate a patient by any means may occur, creating a “lost airway.” This critical airway situation requires the full attention of everyone in the operating room because nothing else matters if the airway is lost. Failure to deliver oxygen and remove carbon dioxide from organs and tissues will quickly result in serious injury to tissues and organs, followed by death (Hagberg et al, 2005). As technology, training, and crisis anticipation have improved during recent decades, deaths associated with airway problems at induction have decreased. However, difficult airway problems during maintenance, emergence, and recovery have not decreased. (Peterson et al, 2005).

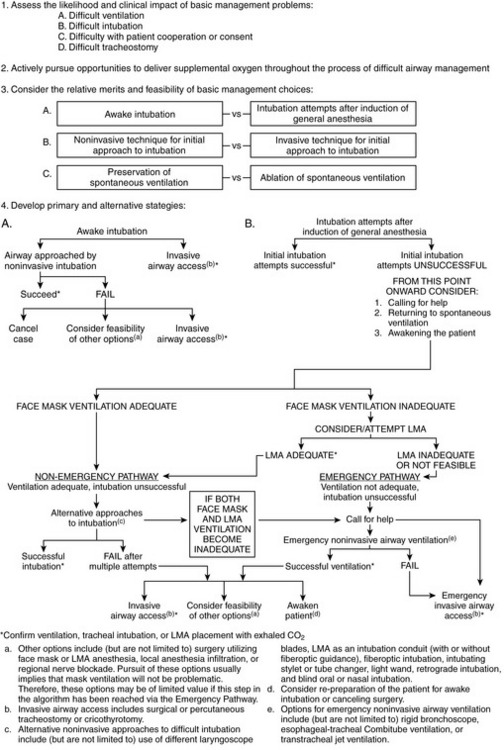

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) has developed Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway (Figure 12-1). As part of the ASA Difficult Airway Algorithm, anesthesia providers aim to avoid problems with careful preanesthetic assessment to allow safe planning for potentially difficult airways identified in advance (ASA, 2003).

Figure 12-1 The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Difficult Airway Algorithm.

(From ASA Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway: Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: an updated report, Anesthesiology 98:1269–1277, 2003.)

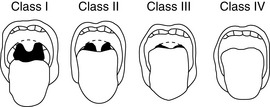

The Mallampati classification of oral opening (Mallampati, 1983) has become well established as one of the simplest elements of airway evaluation, although it is not a stand-alone assessment. Perioperative nurses should be familiar with the Mallampati classification for their own planning at the beginning of a case when word arrives of a patient with a class III or class IV airway, or if they participate in preoperative evaluations themselves (Figure 12-2). Preliminary airway evaluation has moved into the realm of nursing practice (Odom-Forren and Watson, 2005).

Unanticipated difficult airway management may arise from several situations, such as difficult tracheal intubation despite preoperative evaluation deemed adequate; oversedation during a planned “awake” intubation; unrecognized esophageal intubation; airway obstruction by laryngospasm or edema; postoperative bleeding in neck surgery; tumor; vomitus or foreign body; or failure to establish a surgical airway quickly when conventional airway maneuvers fail. It is important to note that patients with OSA have a high incidence of difficult intubation and that patients with difficult intubations have a high incidence of sleep apnea (F. Chung et al, 2008). OSA patients require extra care and planning both for airway management and for their increased postoperative risk for easy oversedation with analgesics (ASA, 2006b). Many cases have been reported of postoperative hypoventilation or respiratory arrest in OSA patients with emergency treatment ending up with a difficult-to-impossible airway by providers unfamiliar with appropriate airway rescue techniques. Although the serious nature of obstructive sleep apnea is recognized by anesthesia providers (S.A. Chung et al, 2008), it is important for all team members to understand its acute and chronic implications.

Familiarity with airway techniques such as LMA, intubating laryngeal mask airway (ILMA) (Liu et al, 2008), lightwands (Massó et al, 2006), and videolaryngoscopes allow perioperative nurses to assist anesthesia providers with airway rescue attempts and to document these techniques appropriately. Although such documentation may not be part of formal perioperative nursing notes, they may be considered analogous to Code Blue records; even informal notes and times can be helpful to the anesthesia provider who must later create a detailed report of the crisis.

Difficult Airway Classification

The steps for handling such a crisis are outlined in the ASA Difficult Airway Algorithm (ASA, 2003). Although perioperative nurses do not perform airway rescue, they must be familiar with basic knowledge of the algorithm’s steps. With the possibility that movement through the algorithm’s steps may fail to secure the airway by various endotracheal intubation techniques, perioperative nurses must anticipate and prepare for a rapid surgical airway.

Any airway difficulty at the beginning of a procedure sets the stage for extra caution at the end of the procedure, when extubation is considered (and may possibly be delayed for safety reasons). Premature extubation in a difficult airway patient may result in a repeat difficult airway situation, with chance of rescue reduced the second time around, because of airway edema, trauma related to prior attempts, or intrinsic pathologic conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea (Isono, 2009). The airway danger during this period cannot be minimized. Fully awake extubation in the sitting position is mandatory; some suggest extubating over an airway exchange catheter, which is left in the trachea as a conduit to allow rapid blind reintubation if deterioration occurs (Mort, 2007). Transfer planning, documentation, and nursing report must emphasize the critical airway status, which may overshadow an uncomplicated surgical course.

Dental Injury

Dental injury is one of the most common anesthesia complications (Hagberg et al, 2005). All patients should be advised of this risk before anesthesia care, personalized to their own dental status (Anderson and Abbey, 2008). Perioperative nurses should be aware of dental status, as well as dental prostheses. However, every anesthesia provider has anecdotes about dental prostheses discovered after induction of general anesthesia, related to patient’s denial of appliances, staff overlook of prostheses, or some combination of circumstances.

Breathing Problems

The patient with a clear and patent airway (natural, endotracheal tube, or tracheostomy) may risk other breathing complications. Successful breathing requires satisfactory maintenance of both oxygenation and ventilation. Anesthesia providers monitor these two aspects of breathing very closely: oxygenation with pulse oximetry (SpO2) and ventilation (removal of CO2) with capnography. Every anesthesia technique has risks that could interfere with oxygenation, ventilation, or both (Morgan et al, 2006).

Laryngospasm

Laryngospasm can be provoked by secretions, sudden stimulation, pain, and airway manipulation. In patients who are most at risk for laryngo-spasm, such as children with airway surgery, many airway providers try to avoid the problem by extubating the child in a deeper plane of anesthesia, after return of spontaneous ventilation; they support the airway by face mask with 100% oxygen until the child awakens (Morgan, 2006).

A sputtering cough and gasp indicates the breaking of the spasm. However, the patient requires mask oxygenation and close monitoring until full return to consciousness. In an infant or child, a cry or yell for “Mommy” indicates both air movement and return to a higher level of consciousness. Laryngospasm may also occur in adults, although it is less common. After laryngospasm, patients must be monitored for development of negative-pressure pulmonary edema, as discussed later (Mirshab, 2002).

Stridor

Postintubation stridor (commonly called croup in children) is caused by edema of vocal cords or trachea. It is most common in children ages 1 to 4 years, appearing within 3 hours of extubation. The work of breathing is greatly increased by even a few millimeters of edema in a toddler’s airway, which mandates immediate treatment with nebulized racemic epinephrine. Intravenous dexamethasone may be given for prevention (Morgan et al, 2006). The condition is occasionally seen in adults and treated with the same regimen.

Bronchospasm

Bronchospasm can occur just from the insult of placing an endotracheal tube into the trachea of a susceptible patient. Wheezing is the sound of air moving through narrowed airways, much like a whistle. Although wheezing is considered the classic sign of bronchospasm, the most dangerous presentation is a “silent spasm” in which the spasm is so intense that no air can be moved. This intense bronchospasm is most likely to occur with an asthmatic patient during intubation under general anesthesia, when a combination of factors related to disease, medications, and mechanical insult (laryngoscopy and intubation) combine to result in bronchospasm. Severe bronchospasm may result in reduced ability to oxygenate or ventilate the patient. The anesthesia provider will treat the bronchospasm with 100% oxygen and aerosol or metered-dose beta-adrenergic agents into the breathing circuit. The inhalational anesthetic agents are also bronchodilators. Steroid-dependent asthmatics may also receive a dose of intravenous hydrocortisone (Morgan et al, 2006). The severity of the episode and its response to treatment will be evaluated by the anesthesia provider and the surgeon before proceeding with surgery or for postoperative care planning. New postoperative arrangements for an intensive care bed may be required.

Aspiration of Gastric Contents

Many patients believe that nothing by mouth (NPO) status is imposed to prevent the inconvenience and discomfort of postoperative nausea and vomiting. They have not been educated about the serious morbidity and mortality that can follow aspiration of gastric contents; the low acidic pH of gastric acid may create a chemical pneumonitis that can be widely spread through the lungs if the aspirated volume is greater than 0.4 mL/kg and the pH is less than 2.5 (Morgan et al, 2006). If food particles, blood, small objects, or teeth are aspirated, severe hypoxemia can follow because of airway obstruction, development of atelectasis, and pneumonitis. In the most-dreaded scenario, the pathologic response accelerates into full-blown respiratory distress syndrome, which may culminate in death.

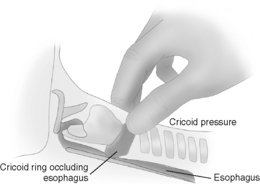

It is essential to know how to identify the cricoid ring (which is the only tracheal ring that is a full circle; all the others are C-shaped, with the open section toward the spine). The large shield-shaped thyroid cartilage (“Adam’s apple”) is the most prominent landmark of the upper trachea with its bottom midmargin at the top of a small, soft elliptical space (Figure 12-3). This indentation is the cricothyroid space (where emergency cricothyroidotomy is done). The strip of cartilage just below the cricothyroid space is the cricoid ring. In a supine unconscious patient, firm pressure on this circular cricoid cartilage will occlude the esophagus and prevent regurgitation of gastric contents into larynx and lungs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree