INTRODUCTION

Anemia is a common medical problem worldwide, affecting approximately one quarter of the world’s population, especially children, pregnant and premenopausal women, the elderly, and the chronically ill.1,2,3,4,5,6,7 Anemia is not so much a disease as a sign or symptom. There are three broad causes of anemia: (1) blood loss, (2) decreased red blood cell production, and (3) increased red blood cell destruction.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Anemia is a reduced concentration of red blood cells (RBCs) from the normal ranges based on age, gender, and race.8 In healthy persons, normal erythropoiesis ensures that the concentration of RBCs present is adequate to meet the body’s demand for oxygen and that the destruction of RBCs balances the production. The average life of the circulating erythrocyte is approximately 110 to 120 days. Any process or condition that results in the loss of RBCs, that impairs RBC production, or that increases RBC destruction will result in anemia if the body cannot produce enough new cells to replace those lost (Table 231-1). It is not uncommon for more than one mechanism to produce anemia in the same individual.

| Mechanism | Example |

|---|---|

| Loss of red blood cells by hemorrhage | Acute GI bleeding |

| Increased destruction | Sickle cell disease Drug-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemia |

| Impaired production | Nutritional deficiency anemia (iron, folate) Aplastic or myelodysplastic anemia |

| Dilutional | Rapid IV crystalloid infusion |

Quantification of the erythrocyte concentration is reflected in (1) RBC count per microliter, (2) hemoglobin concentration, and (3) hematocrit (percentage of RBC mass to blood volume). Normal RBC values for adults vary between genders, with small variations for ethnicity and age (Table 231-2).

| Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|

| Red blood cell count (million/mm3) | 4.5–6.0 | 4.0–5.5 |

| Hemoglobin (grams/dL) | 14–17 | 12–15 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 42–52 | 36–48 |

| Mean corpuscular volume (fL) | 78–100 | 78–102 |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin (picograms/cell) | 25–35 | 25–35 |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (grams/dL) | 32–36 | 32–36 |

| Red cell distribution width (%) | 11.5–14.5 | 11.5–14.5 |

| Reticulocytes (%) | 0.5–2.5 | 0.5–2.5 |

The body responds to anemia in several ways in order to blunt the effect of a reduction in the oxygen-carrying capacity. The mechanisms vary, depending on the rapidity of onset, the degree of anemia, and the underlying condition of the patient. In acute forms of anemia that result from intravascular volume loss, the peripheral vasculature compensates by vasoconstriction, while the central vasculature vasodilates to help preserve blood flow to vital organs.9 As the condition worsens, systemic small-vessel vasodilation will occur, allowing increased blood flow to tissues. These mechanisms result in decreased systemic vascular resistance, increased cardiac output, and often tachycardia. Along with these changes, the RBCs themselves enhance their ability to release oxygen to the tissues. If the anemia is chronic in nature, there is commonly an increase in plasma volume that maintains total blood volume at a constant level. Finally, anemia will result in the stimulation of erythropoietin as a result of tissue hypoxia and breakdown products from RBC destruction. New immature erythrocytes, known as reticulocytes, will appear in the blood within 3 to 7 days.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The severity of signs and symptoms related to anemia depends on several factors: the rate of development of anemia (acute vs chronic), the extent of anemia that is present, the age and general physical condition of the patient, and other existing comorbidities. Children and young adults, for example, may tolerate a significant decline in RBC volume with minimally altered vital signs until they become acutely hypotensive, whereas elderly patients frequently have other comorbidities that make physiologic compensation challenging.3,4 Patients with chronic and slowly developing anemia may have no complaints even with hemoglobin levels as low as 5 to 6 grams/dL. Typically, most otherwise healthy adults will be symptomatic when hemoglobin levels decrease to about 7 grams/dL.

Patients with chronic anemia may note weakness, fatigue, dizziness, lethargy, dyspnea with minimal exertion, palpitations, and orthostatic symptoms. Specific historical features can be helpful in the identification and diagnosis of anemia; a history of recent trauma, hematochezia, melena, hemoptysis, hematemesis, hematuria, or menorrhagia suggests possible anemia. More subtle historical features include relevant comorbidities such as peptic ulcer disease, chronic liver disease, and chronic renal disease. Specific inquiries about the use of antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents should be made.

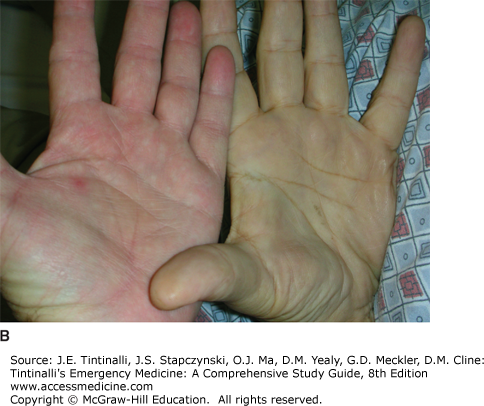

Physical exam findings that may be present in patients with clinically significant anemia include tachycardia; skin, nail bed, and mucosal pallor; systolic ejection murmur; bounding pulse; and widened pulse pressure (Figure 231-1). Signs of easy bleeding or bruising suggest a coagulation disorder. Evidence of jaundice and hepatosplenomegaly suggests hemolysis. Unusual skin ulcerations, peripheral neuropathy, or neurologic signs such as ataxia or altered mental status may be evidence of nutritional deficiencies. Additional manifestations may depend on comorbid illnesses. For example, a patient with preexisting angina may find that episodes of chest pain are markedly worsened when anemia is present.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree