Chapter 32

Allergies to Antibiotics

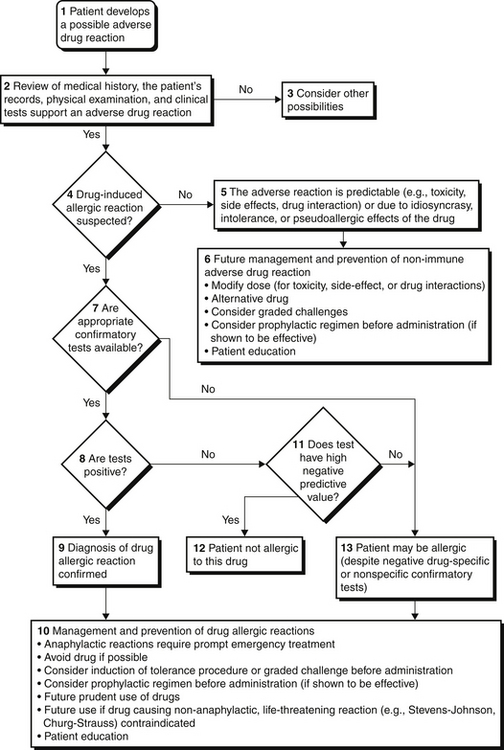

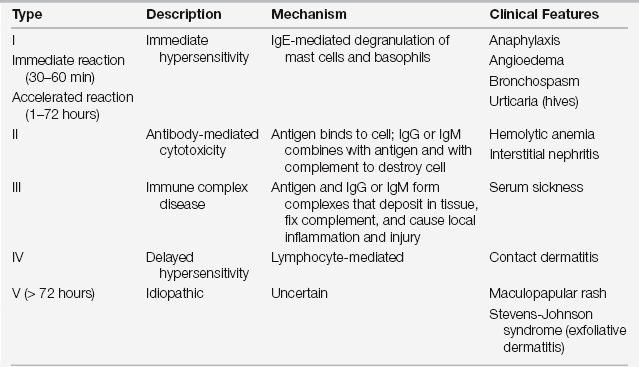

Drug reactions are classified into two major groups: predictable (type A, from known pharmacologic properties, can occur in anyone) and unpredictable (type B, uncommon, restricted to a vulnerable subpopulation) (Figure 32.1). Unpredictable reactions include drug allergy (immunologic), pseudoallergic reactions, drug intolerance, and idiosyncratic reactions. Serious outcomes can be associated with immediate hypersensitivity allergic reactions known as a type I reaction, based on the four traditional types of immunologic reactions of the Gell and Coombs classification system (Table 32.1). This chapter focuses on the evaluation and prevention of potentially life-threatening immediate hypersensitivity reactions to antibiotics.

TABLE 32.1

Classification of Allergic Reactions (Gell and Coombs)

IgE, immunoglobulin E; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M.

Modified from Weiss ME, Adkinson NF: Immediate hypersensitivity reactions to penicillin and related antibiotics. Clin Allergy 18:515-540, 1988.

Evaluations of Patients with a History of Antibiotic Allergy

Beta-lactam antibiotics are among the most important causes of allergic reactions. This group includes penicillin and its semisynthetic chemical derivatives (such as ampicillin and amoxicillin) and other beta-lactam antibiotics including cephalosporins, carbapenems, and monobactams. Approximately 10% of patients report a history of penicillin allergy; however, up to 90% of these patients may be able to tolerate penicillin after a complete evaluation (Figure 32.1). A carefully obtained history of previous drug reactions to this class of antibiotics is critical to the allergy evaluation. An accurate history may be challenging in the ICU setting where patients are frequently sedated or intubated and may be receiving multiple medications. Family members or the patient’s primary care physician as well as outpatient electronic medical records may be valuable sources of the relevant history. Inquiry should be obtained for the name of the drug, time when previous exposure occurred, reason for treatment, timing of previous reaction (time elapsed from drug administration to the occurrence of adverse events), characteristics of the reaction (organ systems involved), medications in use at the time of the reaction, management required for treatment of the reaction, subsequent exposure to the drug, similar symptoms in absence of the drug (such as chronic urticaria), and whether the patient had an underlying condition that favored a reaction to a medication. For example, patients with Epstein Barr virus infections who are given ampicillin tend to develop a rash that looks like an allergic reaction but is not immunologically mediated. Information is then collected regarding all the current medications, both prescription and nonprescription, and similarly reviewed. Physical examination and laboratory studies to assess for organ system involvement are also crucial to the evaluation.

Indications for Skin Testing

Skin test results to penicillin may remain negative up to 6 weeks after an allergic reaction to beta-lactam antibiotics. Skin testing should, therefore, be repeated after this interval if it is initially negative and the test is clinically indicated. A history of penicillin-induced exfoliative dermatitis (i.e., Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis [see Chapter 43]) is an absolute contraindication to skin testing as well as to the administration of beta-lactam antibiotics. The approach to a patient with a history of a beta-lactam allergy is summarized in Figure 32.1.

The risk of having an adverse reaction to the skin test reagents is less than 1%, but systemic and fatal reactions occur. The risk of becoming sensitized to beta-lactam antibiotics as a result of penicillin skin testing is also less than 1%. Resensitization after oral treatment with penicillin is rare, and repeat skin testing is not required in patients who have tolerated 1 or more oral courses of penicillin. Resensitization after high-dose parental penicillin may be more likely. Retesting may be considered in individuals with recent or particularly severe previous reactions.

Evaluation of Allergies to Cephalosporins and Other Non–Beta-Lactam Antibiotics

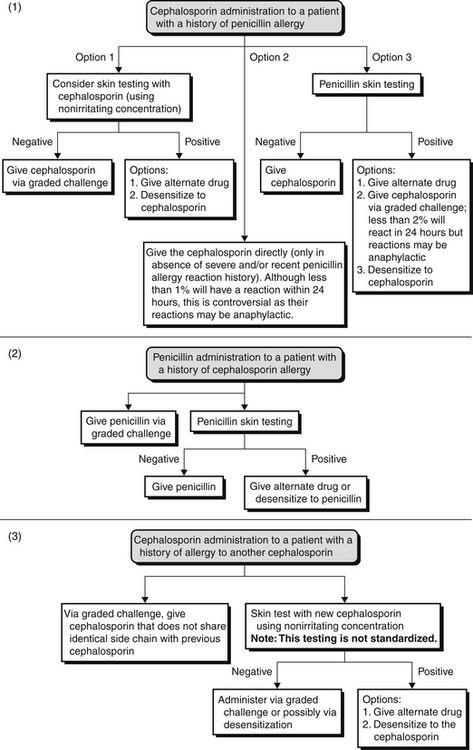

Therefore, depending on the reaction history, these patients should be administered cephalosporin through graded challenge or desensitization (induction of tolerance procedure). If a patient has a history of a cephalosporin allergy but a negative penicillin skin test result, one should consider a penicillin, not a cephalosporin (Figure 32.E1). ![]()

Allergic cross-reactivity between shared R-group side chains should also be considered. Amoxicillin and certain cephalosporins share identical R-group side chains (see Tables 32.E1 and 32.E2). ![]() Research has shown that 12% to 38% of patients proved to be selectively allergic to amoxicillin reacted to cefadroxil yet were able to receive penicillin. Therefore, patients with an amoxicillin or an ampicillin allergy should avoid cephalosporins that share identical R-group side chains or undergo desensitization of these cephalosporins.

Research has shown that 12% to 38% of patients proved to be selectively allergic to amoxicillin reacted to cefadroxil yet were able to receive penicillin. Therefore, patients with an amoxicillin or an ampicillin allergy should avoid cephalosporins that share identical R-group side chains or undergo desensitization of these cephalosporins.

Reliable skin tests to other classes of antibiotics, such as vancomycin or sulfonamide-type drugs, are not commercially available. However, skin testing with nonirritating concentrations of the drug may provide useful information (see Table 32.E3). ![]() This study collected data on healthy subjects without drug allergies to determine baseline nonirritating intradermal skin test concentrations for 15 commonly prescribed parenteral antibiotics. Serial 10-fold dilutions were prepared and tested in these individuals to determine the lowest dilution that did not elicit an irritant response. This concentration was then termed the nonirritating concentration (NIC). Under these circumstances, a positive skin test using the NIC of a drug suggests that the patient has drug-specific IgE antibodies and, for that reason, is at risk for a reaction and should receive an alternate, non-cross-reacting antibiotic or undergo induction of tolerance (also called desensitization). On the other hand, a negative NIC skin test result does not rule out the presence of drug-specific IgE antibodies because it is possible that a drug metabolite not present in the test reagent may be the relevant allergen.

This study collected data on healthy subjects without drug allergies to determine baseline nonirritating intradermal skin test concentrations for 15 commonly prescribed parenteral antibiotics. Serial 10-fold dilutions were prepared and tested in these individuals to determine the lowest dilution that did not elicit an irritant response. This concentration was then termed the nonirritating concentration (NIC). Under these circumstances, a positive skin test using the NIC of a drug suggests that the patient has drug-specific IgE antibodies and, for that reason, is at risk for a reaction and should receive an alternate, non-cross-reacting antibiotic or undergo induction of tolerance (also called desensitization). On the other hand, a negative NIC skin test result does not rule out the presence of drug-specific IgE antibodies because it is possible that a drug metabolite not present in the test reagent may be the relevant allergen.

A detailed history is always critical for the appropriate evaluation of allergic reactions to medications. The specific drug in question should be avoided unless life-threatening infections demand its use and an induction of tolerance procedure (also called desensitization) would then be necessary. In situations where there is a definite need for a particular medication and no alternative medication is available, induction of tolerance should be considered. This procedure involves the administration of incremental doses of the drug, which temporarily allow tolerance to the drug. As in skin testing, induction of drug tolerance should almost never be performed if the reaction history includes a severe non-IgE-mediated reaction such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS); toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN); drug rash, eosinophilia, and systemic symptoms (DRESS); hepatitis; or hemolytic anemia.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree