Airway Assessment and Management for Procedural Sedation

Angela Stone

Mark Freedman

Introduction

Ensuring adequate patient ventilation and oxygenation during procedural sedation is essential.

Most common adverse event during procedural sedation is respiratory depression.

Appropriate assessment involves recognizing challenges in airway management and preparing for respiratory depression and apnea.

Procedural sedation requires a dedicated physician and nurse skilled in airway management and knowledgeable about potential complications.

Airway Assessment

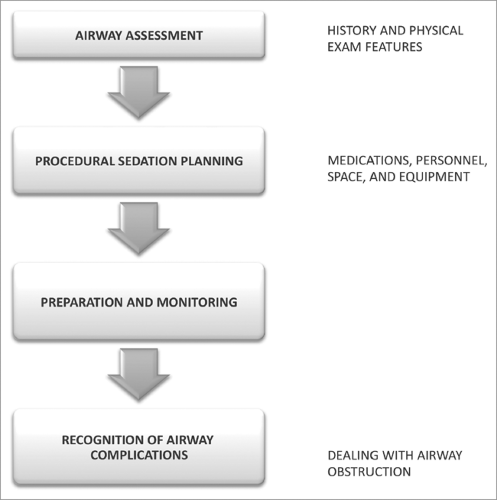

Assessment of the patient’s airway is essential to anticipate challenges and complications to managing potential respiratory depression (see Figure 2.1).

The goal of airway evaluation is to identify characteristics that may predispose a patient to airway obstruction, difficult bag-valve mask (BVM) ventilation, or a difficult intubation.

Predicting these challenges will allow preparing for appropriate airway adjuncts and tailor clinical observation.

Patient History

A brief assessment of the patient’s medical history may alert you to conditions that may predispose to challenges in airway management:

History of difficult intubations in the past.

Modified oral or airway anatomy (genetic or prior surgery).

History of airway problems (e.g., reactive airway disease and sleep apnea).

Physical Examination

A thorough physical examination is necessary to adequately assess a patient’s airway.

The patient should be observed and examined and the following documented in the airway assessment:

Teeth (prominent incisors, crowns, dentures, loose or chipped teeth).

Cervical spine mobility.

Have the patient flex and extend the head and neck.

Mouth Opening.

Have the patients open their mouth as wide as possible.

The patient should be able to insert three fingers between the incisors ideally.

Size of the mandible is equal to hyomental distance and thyromental distance.

During laryngoscopy, the tongue is pushed into the mandibular space by the blade.

If the mandible is too small, there will be insufficient room for the tongue to be displaced forward while the posterior tongue and epiglottis will obstruct the view of the glottis.

Hyomental distance – distance from hyoid bone to mentum (chin).

Three fingerbreadths of the patient is equal to adequate distance.

Thyromental distance – distance from the thyroid cartilage (Adam’s apple) to the undersurface of the mandible.

Two fingerbreadths of the patient is equal to adequate distance.

Oral Access

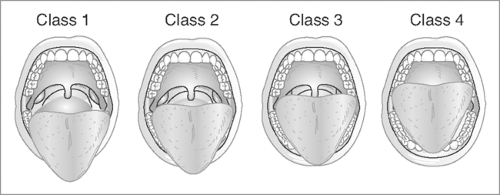

The size of tongue in relation to the oral cavity is assessed using the Mallampati classification.

Mallampati Classification

The patient should be examined sitting with the head of the bed in a neutral position, the mouth opened as wide as possible, and the tongue protruded maximally.

Visibility of the oral and pharyngeal structures (i.e., uvula, tonsillar pillars, and soft palate) are used to predict difficulty with ventilation and intubation.

For example, Class IV (hard palate visible only) suggests potentially difficult ventilation and intubation (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2: Airway assessment using the Mallampati classification.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access