Airway

An obstructed airway is a medical emergency requiring immediate treatment. Where possible, patients at risk should be identified early so that airway obstruction can be prevented. Although upper airway obstruction may be gradual in onset it more commonly progresses very rapidly. Continuous assessment is required to identify signs of impending airway obstruction.

Whilst the ultimate aim when managing airway disorders is to obtain a definitive airway, patients die because of failed oxygenation and ventilation—not failed intubation. Basic airway management skills (e.g. bag and mask ventilation using simple airway adjuncts) are crucial.

Causes

Internal obstruction

Foreign body or tumour.

Airway bleeding/trauma.

Aspirated vomit.

Upper airway infection (e.g. epiglottitis, retropharyngeal abscess).

Swelling/oedema:

Angio-oedema (ACE inhibitors, aspirin, hereditary C1-esterase deficiency)

Anaphylaxis

Following upper airway interventions or surgery (including postextubation laryngeal oedema)

Airways burns or inhalation of smoke/toxic fumes

External obstruction

Swelling/oedema: neck trauma, external mass, or tumour.

Haematoma (especially in coagulopathic or anticoagulated patients).

Neck trauma

Following thyroid or carotid surgery

Following internal jugular line insertion

Neurological causes

Diminished level of consciousness (e.g. intoxication, head injury/CVA, cardiac arrest).

Laryngospasm (especially in semi-conscious patients).

Paralysis of vocal cords.

Neurological disease (e.g. myasthenia gravis, Guillain-Barré, polyneuritis, or recurrent laryngeal nerve damage)

Inadequate reversal of muscle relaxants

Presentation and assessment

Partial obstruction

Anxiety.

Patient prefers sitting, standing, or leaning forward.

Inability to speak or voice change (muffled or hoarse voice).

Stridor (inspiratory noise accompanying breathing) or noisy breathing.

Obvious neck swelling.

Lump in throat, difficulty in swallowing.

Choking.

Coughing.

Drooling.

Respiratory distress:

Tachypnoea and dyspnoea

Use of accessory muscles of respiration

Paradoxical breathing: indrawn chest and suprasternal recession

Tracheal tug

‘Hunched’ posture

Total or near-total obstruction

Hypoxia, cyanosis, hypercapnia.

Bradycardia, hypotension.

Diminished or absent air entry.

↓consciousness.

Cardiac/respiratory arrest, where bag and mask ventilation impossible.

Investigations

Diagnosis is mainly clinical and some investigations may have to wait until the patient is stabilized with a secure airway.

ABGs (hypoxia, hypercapnia).

Clotting screen (coagulopathy).

Blood cultures and oropharyngeal swabs1 where appropriate.

Imaging: neck X-ray (AP & lateral), CXR, or CT scan may be required (may reveal neck or mediastinal masses or foreign bodies).

Fibreoptic endoscopy or direct laryngoscopy.1

Although nasendoscopy will potentially allow a view of the airway and aid diagnosis, it requires skill to be done safely

Direct laryngoscopy should not be attempted unless the airway is already secured, or all preparations are in place to immediately secure the airway (see pp.20-21).

pp.20-21).

Differential diagnoses

Equipment failure (e.g. incorrectly assembled self-inflating ambu-bag).

ETT or tracheostomy obstruction (see pp.40 and 45).

pp.40 and 45).

Conditions which result in noisy breathing:

Bronchospasm

Hysterical stridor

Conditions which result in difficulty breathing spontaneously or high airway pressures when ventilating patient:

Bronchospasm

Tension pneumothorax

Conditions which result in patients adopting a sitting or leaning forward position:

SVC obstruction

Cardiac tamponade

Immediate management

100% O2, pulse oximetry.

Assess condition of patient and likely cause of airway obstruction.

Support ventilation with bag and mask if required.

If patient has suffered cardiac/respiratory arrest:

Support/open airway; use adjuncts (oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal airways) and suction.

Remove obvious obstruction and commence CPR.

If patient is peri-arrest:

Call for skilled help: anaesthetist, ENT surgeon.

Obstruction requires immediate laryngoscopy/tracheal intubation.

Surgical airway, i.e. cricothyroidotomy or tracheostomy for total obstruction if the previous points fail.

If airway obstruction is due to diminished consciousness:

Call for skilled anaesthetic assistance.

If traumatic: assume C-spine injury and asses for other injuries.

Consider replacing hard-collar with manual in-line stabilization (often helpful when supporting airway, required prior to intubation).

Ensuring an adequate airway always overrides concerns about potential C-spine injuries.

Support/open airway; use adjuncts (oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal airways) and suction.

Support ventilation with bag and mask if required.

Proceed to definitive airway, most commonly using a rapid sequence intubation ( p.522).

p.522).

Cricothyroidotomy or tracheostomy is indicated in the event of failed intubation.

If airway obstruction is due to airway swelling, infection, or physical obstruction:

Call for senior help (anaesthetic and ENT).

Formulate an airway management plan and arrange for equipment to be available (e.g. plan A: endotracheal intubation; plan B: laryngeal mask airway; plan C: temporary cricothyroidotomy); see pp.26 and 27 for difficult airway equipment and failed intubation drill.

pp.26 and 27 for difficult airway equipment and failed intubation drill.

Arrange equipment for inhalational induction (anaesthetic machine with an anaesthetic gas: sevoflurane or halothane):

Consider transferring patient to an operating theatre where this equipment is present if the patient is stable

Temporary measures which may be used whilst arranging the equipment/transfer include: nebulized adrenaline (5 mg/5 ml 1:1000 in a nebulizer) and/or humidified oxygen or Heliox.

Early intubation should be considered to reduce the risk of sudden deterioration and airway obstruction:

Cricothyroidotomy or tracheostomy is indicated in the event of failed intubation and ventilation, or as initial management plan under local anaesthesia.

Other considerations requiring simultaneous treatment:

Haematoma after neck surgery: remove dressings, cut open sutures.

Airway bleeding ( p.36): correct coagulopathy.

p.36): correct coagulopathy.

Laryngospasm: support ventilation with bag and mask ventilation, apply PEEP (easier using a Water’s or C-circuit); although low-dose propofol, 10-20 mg IV, and low-dose suxamethonium, 10-15mg IV have been successfully used, intubation must be immediately available.

Inadequate reversal of muscle relaxants: treat for laryngospasm, consider reversal with IV neostigmine 2.5 mg mixed with glycopyrronium bromide 0.5 mg (only works if reversing a non-depolarizing muscle relaxant that is already beginning to wear off); alternatively sugammadex 2-4 mg/kg IV may reverse muscle relaxation with vecuronium or rocuronium.

Postextubation oedema: nebulized adrenaline, IV steroids.

Angio-oedema which is non-allergic: this should be treated as allergic in the first instance (see earlier in list), where there is a clear history of hereditary angio-oedema consider C1 esterase inhibitor concentrate, icatibant, tranexamic acid, or danazol (seek specialist advice first).

In stable patients where diagnosis/degree of obstruction is in doubt, nasal endoscopy performed by an experienced ENT surgeon may help. Be prepared to intubate or perform cricothyroidotomy/tracheostomy if total airway obstruction is provoked.

Transfer to critical care environment for close observation.

Further management

Only if condition is stable and the airway obstruction has been relieved:

Nurse patient 30-45° head up to promote venous drainage.

Consider IV dexamethasone to reduce any further airway swelling.

Ventilation and sedation for a number of days on ICU may be required for intubated patients until the cause of obstruction resolves.

Adopt a lung-protective ventilation strategy ( p.53).

p.53).

Surgical or microbiology opinions may be required.

Supportive measures for sepsis may be required (see p.322).

p.322).

Assess airway swelling (laryngoscopy and/or cuff-leak test) prior to extubation.

Where intubation is likely to be prolonged, or airway obstruction may recur after extubation, consider elective tracheostomy.

Pitfalls/difficult situations

Delaying intubation may make a difficult intubation impossible.

Deterioration to complete obstruction may progress rapidly over a few hours.

Cardiovascular collapse may mask airway signs.

Airway interventions in a patient with a partially obstructed airway can provoke complete airway obstruction.

Insertion of oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal airway in patients with retropharyngeal abscess may burst the abscess and soil the airway.

Other, non-airway, indications for intubation also exist (see p.12).

p.12).

It is important to recognize patients in whom endotracheal intubation is likely to be difficult (see p.24).

p.24).

Obtaining a definitive airway via endotracheal intubation or surgical tracheostomy can be challenging in the face of airway obstruction; the priority is always to maintain oxygenation.

Cricothyroidotomy (see p.528) should only be attempted by inexperienced operators in circumstances where the patient is otherwise likely to die.

p.528) should only be attempted by inexperienced operators in circumstances where the patient is otherwise likely to die.

The commonest technique of intubation, the rapid sequence intubation, is described on p.522 so that non-anaesthetic trained critical care practitioners are familiar with a technique they may be required to assist with.

p.522 so that non-anaesthetic trained critical care practitioners are familiar with a technique they may be required to assist with.

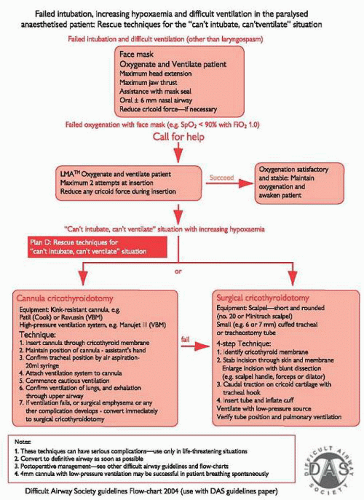

Failed intubations occur in approximately 1 in 2000 routine intubations and up to 1 in 250 rapid sequence intubations.

Difficult intubation may lead to failure to maintain oxygenation, airway protection, or trauma from repeated intubation attempts.

‘Can’t intubate/can’t ventilate’ situations account for 25% of all anaesthetic deaths.

Studies have highlighted the importance of proper airway assessment, combined with the creation of an airway management plan based on a plan A, plan B, plan C approach.

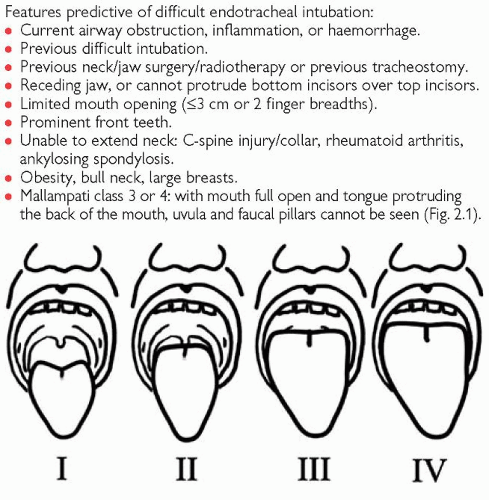

Features predictive of difficult endotracheal intubation:

Current airway obstruction, inflammation, or haemorrhage.

Previous difficult intubation.

Previous neck/jaw surgery/radiotherapy or previous tracheostomy.

Receding jaw, or cannot protrude bottom incisors over top incisors.

Limited mouth opening (≤3 cm or 2 finger breadths).

Prominent front teeth.

Unable to extend neck: C-spine injury/collar, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylosis.

Obesity, bull neck, large breasts.

Mallampati class 3 or 4: with mouth full open and tongue protruding the back of the mouth, uvula and faucal pillars cannot be seen (Fig. 2.1).

Ways to reduce intubation difficulties

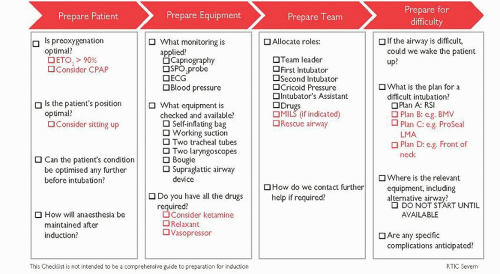

(See Fig. 2.2.)

Thorough assessment of airway and previous anaesthetic history.

Formulate and communicate airway management strategy: plan A, plan B, plan C as per DAS guidelines (see p.27).

p.27).

Consider awake fibreoptic intubation (if appropriate) if potential exists for difficult laryngoscopy with difficult bag-mask ventilation.

Prepare equipment.

Ensure senior help available.

Position patient appropriately and pre-oxygenate.

Ensure appropriate abolition of airway reflexes before intubation.

Equipment for intubation

A range of facemasks and means of ventilating (i.e. self-inflating bag).

Range of cuffed ETTs (size 6.5-10).

Lubricant.

10-ml syringe (for inflating ETT cuff).

Laryngoscope with Mackintosh blades size 3 and 4.

Bougie, stylet.

Tape or ties.

Stethoscope.

End-tidal CO2 monitoring.

Suction apparatus, tubing; Yankauer suckers and suction catheters.

Magill forceps.

Equipment for difficult intubation

Small endotracheal tubes (size 5-6).

Special laryngoscopes (McCoy, short-handled, polio blade).

LMAs (sizes 3, 4, 5) (intubating LMA if available).

Airway exchange catheters.

Intubating fibreoptic scope.

Berman airways.

Emergency cricothyroidotomy kits:

Needle cricothyroidotomy set

Surgical cricothyroidotomy equipment

Jet ventilator.

Recognizing misplaced endotracheal tube

Oesophageal intubation

Bronchial intubation

Unilateral air entry (listen with stethoscope in both axillae).

Hypoxia (may be gradual onset).

High airway pressures.

Position of ETT at lips too far (average position at the lips for females = 20-22 cm, for males = 22-24 cm).

Auscultation may be unreliable, particularly in the obese.

1Airway interventions in a patient with a partially obstructed airway can provoke complete airway obstruction.

Further reading

Cook TM, et al. Fourth National Audit Project. Major complications of airway management in the UK: results of the Fourth National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Difficult Airway Society. Part 2: intensive care and emergency departments. Br J Anaesth 2011; 106: 632-42.

See Fig. 2.3.

Trauma to the face and neck can directly damage airway structures or compress the airway as a result of swelling/haematoma formation; or it may cause airway obstruction because of blood, bone, or tooth debris.

Causes

Blunt force trauma: commonly car crash or assault or hanging.

Penetrating trauma: commonly stabbing or shooting.

Airway and facial trauma are associated with severe head and C-spine injury and/or intoxication. Injuries include:

Midface: LeFort fractures, associated with base-of-skull fractures (these can collapse soft palate against pharynx and obstruct the airway).

Mandible or zygoma: both may occasionally disrupt the temporomandibular joint limiting mouth opening. Bilateral mandibular fractures can cause posterior displacement of the tongue and airway obstruction.

Larynx: severe injury rapidly leads to asphyxiation.

Trachea: associated with severe thoracic or great vessel damage.

Presentation and assessment

History of trauma or attempted hanging.

Patient prefers sitting, standing, or leaning forward.

Facial disruption, airway haemorrhage, spitting blood, epistaxis.

Dental malocclusion, reduced mouth opening.

Respiratory distress:

Tachypnoea, dyspnoea, hypoxia, cyanosis

Use of accessory muscles of respiration

Paradoxical breathing: indrawing chest and suprasternal recession

Tracheal tug

Diminished or absent air entry, minimal respiratory excursions

Altered consciousness.

CSF rhinorrhoea, racoon eyes, Battle’s sign, haemotympanum.

Laryngeal/tracheal trauma:

Surgical emphysema, neck swelling, bruising, or palpable fracture.

Inability to speak or vocal changes (muffled or hoarse voice).

Stridor (inspiratory noise accompanying breathing) or noisy breathing.

Investigations

Diagnosis is clinical; investigations may have to wait until airway is secure

ABGs (hypoxia, hypercapnia).

FBC, crossmatch, coagulation, U&Es

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

p.98

p.98 p.110

p.110 p.28

p.28 p.26

p.26 p.27

p.27