AGITATED CHILD

LAURA L. CHAPMAN, MD, EMILY R. KATZ, MD, AND THOMAS H. CHUN, MD, MPH

This chapter presents an approach for the diagnosis of the acutely agitated or aggressive child. Additional details of management of the conditions discussed here are found in Chapter 134 Behavioral and Psychiatric Emergencies.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

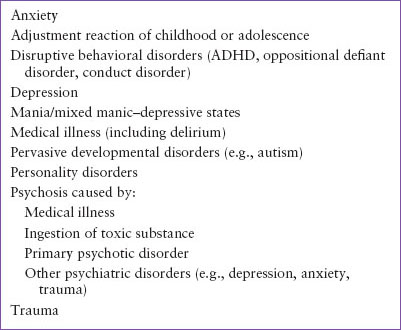

A wide variety of medical and psychiatric conditions can lead to a child’s development of significant agitation and aggression. These disorders are listed in Table 8.1 and include severe psychiatric disturbances, life-threatening medical conditions, and minor aberrations in the child’s ability to respond to stressful events.

Medical Conditions

Agitation, especially in the presence of disorientation, abnormal vital signs, or decreased level of consciousness, should be attributed to an emergent medical cause until proven otherwise. Clinicians should resist the temptation to immediately ascribe agitation or aggression to psychiatric causes, even in children with a pre-existing psychiatric diagnosis. These children remain susceptible to medical illness and are at even higher risk than their peers for engaging in substance use and high-risk behaviors. The first step in evaluating a child with a chief complaint of sudden personality change or confusion is to rule out any potentially life-threatening medical causes.

TABLE 8.1

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF AGITATION AND AGGRESSION IN CHILDHOOD

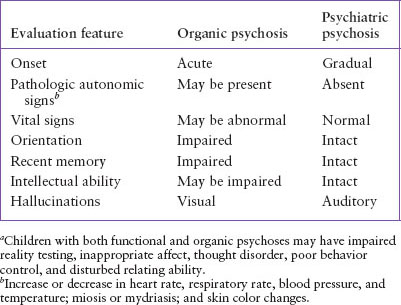

The history and physical examination can provide multiple diagnostic clues to help the emergency physician differentiate medical from psychiatric causes (Table 8.2). In general, medical causes of agitation have an acute onset and the patient is likely to be disoriented, particularly with regard to time and place. Recent memory can be impaired. In addition, hallucinations may be visual, tactile, or gustatory, rather than auditory in nature (auditory hallucinations are less common). In contrast, psychiatric causes of agitation and confusion typically have a gradual onset, often following a prolonged period of progressive social and emotional withdrawal. Hallucinations with psychiatric conditions are most frequently auditory.

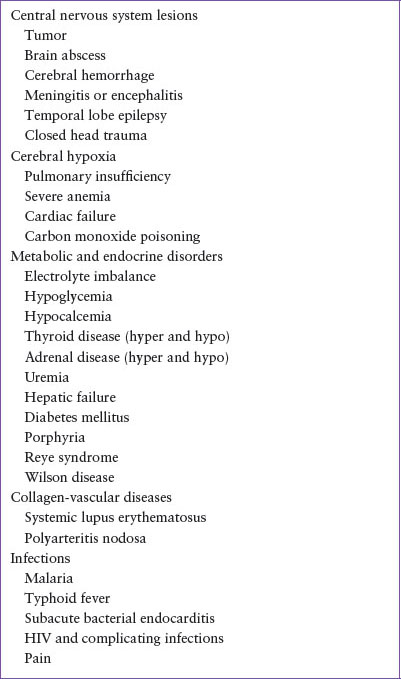

Table 8.3 lists medical conditions that can induce agitation in a child. Most of these diagnoses present acutely. For example, a patient with closed head trauma or a cerebral hemorrhage will present with an acute change in mental status and agitation that worsens over a period of minutes to hours. These patients may also be acutely intoxicated, making the evaluation challenging. Careful assessment of vital signs, and, in this case, head imaging and toxicologic screening will lead to the correct diagnosis. Other medical conditions, such as thyroid disease, diabetes mellitus, and electrolyte imbalances, will present subacutely. These disorders are usually preceded by medication changes or by a period of weeks to months of symptoms such as weight change, hair loss, diarrhea or vomiting, or fatigue. A patient with a chronic condition such as heart or renal disease can present with agitation during a period of acute worsening of their chronic illness. It is therefore critically important to obtain an accurate history of current and previous medical problems.

TABLE 8.2

DIFFERENTIATING FEATURES OF ORGANIC AND PSYCHIATRIC PSYCHOSISa

TABLE 8.3

MEDICAL CONDITIONS THAT MAY LEAD TO AGITATION AND DELIRIUM

A special consideration in pediatrics, especially in the preverbal, autistic, or mentally delayed child, is pain. These children may appear agitated, when in fact they have an acute medical condition or an acute injury. A careful physical examination and a broad diagnostic workup are necessary to fully evaluate these children. Child abuse should always be considered, especially in the autistic or mentally delayed child, as these children have been shown to be at higher risk.

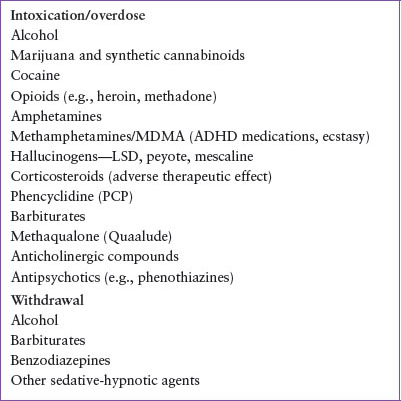

Toxicologic Ingestion or Withdrawal

Acute ingestion of a toxicologic substance, or in the case of a chronic user, withdrawal from a substance, commonly leads to agitation and may lead to psychosis (Table 8.4). In obtaining a history, a frequent important clue in drug intoxication is the acute onset of disordered thinking in the presence of visual hallucinations. A history of drug abuse and the availability of toxic substances are other important historical clues. Intoxication with alcohol, sedatives, antidepressants, anticholinergic agents, and heavy metals can be life-threatening if enough of the agent has been ingested. Withdrawal syndrome in patients habituated to alcohol or sedative-hypnotic agents may likewise result in severe agitation, psychosis, seizure, and death (see Chapter 110 Toxicologic Emergencies).

TABLE 8.4

EXOGENOUS SUBSTANCES CAUSING AGITATION AFTER INGESTION OF SIGNIFICANT QUANTITY OR OVERDOSE, OR DURING WITHDRAWAL WHEN HABITUATED

Delirium

Delirium can be broadly defined as acute, fluctuating global cerebral dysfunction due to a medical condition. The presentation can be quite variable, but the core feature is a disturbance in consciousness with a decreased ability to focus, sustain, or shift attention (Table 8.5). While many delirious patients may be agitated or suffering from hallucinations, others can appear hypoactive, quiet, and withdrawn. Irritability, mood fluctuation, and anxiety are common findings in pediatric patients suffering from delirium. If delirium is present, priorities should be maintaining the patient’s safety while evaluating and treating the underlying cause (Table 8.6).

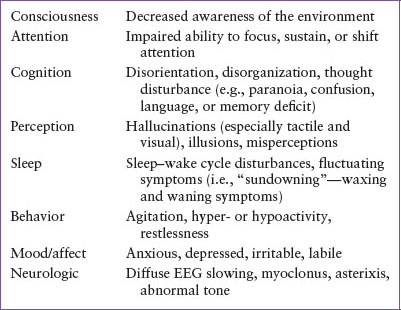

TABLE 8.5

CLINICAL DISTURBANCES OF DELIRIUM

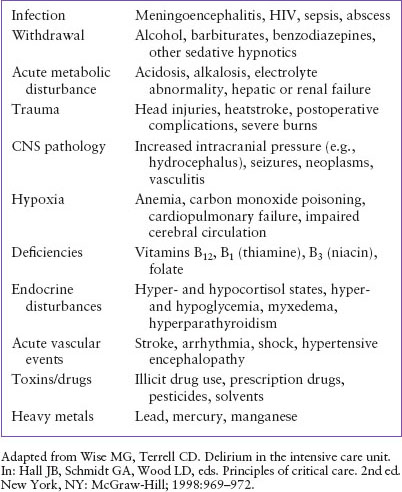

TABLE 8.6

“I WATCH DEATH” MNEMONIC FOR DELIRIUM

Psychiatric Conditions

A number of psychiatric conditions can present with agitation or aggression. Agitation or aggressive behavior may be the final common pathway for a number of psychiatric conditions. These conditions are discussed below and in greater detail in Chapter 134 Behavioral and Psychiatric Emergencies.

Psychotic Disorders

Psychosis refers to a mental state in which major disturbances in thinking, relating, and reality testing occur. They may have hallucinations, delusions (fixed, false beliefs), and/or grossly disorganized behavior and speech. Psychotic patients do not express themselves clearly and have difficulty answering direct questions. They also may be extremely suspicious and hostile. Primary psychotic disorders include brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, schizophrenia, delusional disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. These illnesses share core diagnostic criteria but differ primarily based on duration of symptoms. It is important to note that in children, psychosis is less likely to be due to a primary psychotic disorder such as schizophrenia and more likely due to a medical illness or another psychiatric disorder that can present with psychotic symptoms (e.g., severe anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD], depression, or mania).

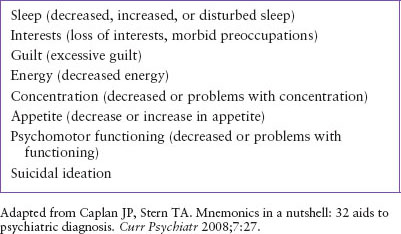

TABLE 8.7

“SIGECAPS” MNEMONIC FOR DEPRESSION

It is useful to assess the child presenting with psychotic symptoms for their level of premorbid functioning as well as any recent stressors. Primary psychotic disorders can present in children who have been previously well adjusted or may have had mild to moderate emotional problems but have been exposed to acute or chronic unmanageable stressor(s) such as trauma or abuse. For children who present with a prolonged prodromal period of progressive social and emotional withdrawal, an eventual diagnosis of a chronic disorder such as schizophrenia is more likely.

Depression

The depressed child who presents to the ED may appear sad, hopeless, anxious, anhedonic, or withdrawn. However, some depressed children present with irritability as their main symptom and deny feeling sad. This irritability can, in turn, lead to agitated and aggressive behavior. Thus, the emergency physician should ask about other common symptoms of depression including depressed mood and a disturbance in “SIGECAPS” (Table 8.7), a family history of mood disorders, and any major recent changes in the child’s life. While depression and resulting irritability can occur in the absence of any major apparent stressors, common precipitants of depression and a sense of hopelessness may include parental divorce or separation, loss of a parent through death, a recent devaluation of personal abilities through poor academic performance, peer rejection, or the onset of significant physical illness. Once depression is identified, it is extremely important to inquire about the presence and nature of any suicidal ideation.

Manic/Mixed Episodes

While mania is primarily associated with elation or elevated mood, the main symptom, especially in children, can be irritability. In fact, signs of elation may be completely absent. As with depression, the irritability can be severe and judgment can be so impaired that children can become aggressive and violent. A manic episode is defined as a 7-day period (or shorter if hospitalization is required) of a persistently elevated or irritable mood along with symptoms of distractibility, indiscretions/hypersexuality, grandiosity, flight of ideas, increased goal-directed activity, rapid or pressured speech, and decreased need for sleep (Table 8.8)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree