(1)

Northern Anesthesia & Pain Medicine, LLC, Eagle River, Alaska, USA

(2)

WWAMI Program, University of Washington School of Medicine, Anchorage, Alaska, USA

Keywords

OpioidOpioid misuseOpioid abuseVulnerabilityDependenceAddictionPrimary preventionSecondary preventionTertiary preventionAgentVectorEnvironmenthostRisk factorImmunityBehavioral immunityEducationScreeningPain managementValuationExpectationCognitive distortionPain catastrophizationFear-avoidanceSelf-efficacyLocus of controlWeaningMotivational interviewingASAM criteriaMedication-assisted treatmentMethadone maintenance therapyOpioid treatment programs (OTPs)BuprenorphineSuboxoneSubutexOffice-based treatment (OBT)NaltrexoneXR-NTXVivitrolAddictionologySubstance abuse rehabilitationAssessmentCounselingTherapyNaloxoneNarcan kitOverdose Education and Naloxone Distribution (OEND)Opioid overdose prevention toolkitNaloxone access lawsGood Samaritan lawsYour practice administrator brings you a notecard mailed from a former heroin-addicted patient whom you had provided medication-assisted treatment (buprenorphine) to in the context of intensive one-on-one counseling in the office, as well as required professional substance abuse rehabilitation counseling, and also participation in community-based mutual support group.

You have not heard from this patient in over a year, and despite successful wean off of substitution therapy (with abstinence from heroin) she did not follow through with extended-release naltrexone injections as advised. For months you feared she had relapsed, and over time you forgot about her.

The notecard is brief but poignant, expressing gratitude for the firm and directive therapy and counseling you delivered in a caring and nonjudgmental manner. She recounts that despite her trepidation and fears, she “came clean” with her family and fiancé and to her relief found not only forgiveness and healing of old relational wounds but also accountability and structure. She has managed to keep her job, and she writes the notecard on her 1-year work anniversary there. She has continued in an active participation role within a “Celebrate Recovery” group in her city and expresses interest in assuming a position of leadership therein.

She has been heroin-free now for over 2 years and states in the closing sentences of the card that she has found resolution of her shame and that the “track marks” on her arms that she previously went to great efforts to conceal now serve as both reminder to her of choices and a lifestyle she cannot see ever returning to. She states that the acceptance and care from her fiancé, family, and new faith community (and its sponsored Celebrate Recovery group) provide her with a sense of fulfillment and purpose that she desires to share with others who struggle with opioid addiction.

Introduction

While pertinent to infectious diseases, the concept of prevention strata (primary, secondary, tertiary) has been widely adopted for many noncommunicable diseases of significance (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, coronary disease, cancer, etc.) and more recently has been proposed as a reasonable schema to organize efforts targeted at reductions in opioid (and other substance) dependence [1, 2].

Primary prevention is that which seeks to avert the onset of disease or injury in individuals who have not yet experienced it; this is prevention as most people know it. Modification of risk factors when possible (e.g., vaccination, quarantine of infected individuals, lifestyle modifications) comprises the essence of primary prevention. Opioid exposure reduction, while ultimately the responsibility of the individual host, is obviously also a function of vector (prescriber) modification in this paradigm and comprises the bulk of the subject matter of Part III of this book. Nonetheless, it is considered again in this chapter in the context of the host, as the actual physical exposure to the agent is a function of the host using the medication either in compliance with or in deviation from the prescription. As discussed in Chap. 1, a critical and assumed ingredient in a population’s effort to end an epidemic is the inherent desire of the vulnerable population to avoid the agent. Unfortunately in the case of addiction, rational self-preservation instincts are surrendered or are conquered by the overwhelming compulsion to seek the addictive substance (or activity) regardless of the results, as discussed in some detail in Chap. 9.

Screening for those at risk of developing, or those who have already developed mild to moderate, or at least clandestine opioid dependence was discussed in the previous chapter. Secondary prevention aims to identify (generally by screening programs) and reverse if possible the early effects of the disease or injury state or at least retard its progression. Examples from the noncommunicable disease world include diet and exercise changes as well as antiplatelet pharmacotherapy in cases of known coronary disease and similar lifestyle modifications and hypoglycemic pharmacotherapies in cases of known diabetes.

Without clear-cut objective biomarkers for opioid dependence (such as are available for most infectious and noncommunicable diseases) determining the absence vs. presence of disease is difficult at best, often rendering the line between primary and secondary prevention blurry. Furthermore, interventions at these levels share considerable overlap. Clinical strategies for both primary prevention and also reversal of early/mild opioid dependence are presented again briefly, based on recent national clinical practice guidelines and also the author’s experience. More detailed components of these strategies may be found in previous chapters.

Tertiary prevention consists of efforts to attenuate the consequences of established disease (“harm reduction”) and comprises the final subject matter of the chapter.

Primary Prevention

Primary prevention can be considered as simply taking steps to ensure that hosts do not develop a disease. It is prevention as most of us think of it. Preventing the development of disease may be a straightforward matter in some situations, such as we have been fortunate enough to have discovered with the development of effective vaccines for several viral and some bacterial infections. In other situations, e.g., Type II diabetes, it may be a very complicated matter without the option of simple immunization, relying instead upon alteration of modifiable risk factors through intensive and sustained lifestyle changes (diet, exercise, and so on.)

As has been discussed previously, elimination of the agent or the vector is neither feasible nor desirable; attenuation of host vulnerability is both. Reducing exposure is one way to reduce host vulnerability, but it is a fragile tactic dependent upon factors (individual and societal/environmental) that are highly unpredictable. Restriction of opioid availability certainly plays a role in the overall effort to reduce dependence, but in addition to the unfeasibility of elimination, the agent may mutate, so to speak. While the analogy breaks down somewhat, just like influenza strains, oxycodone becomes heroin or worse. Similarly, reduction in euphoric/hedonic reward properties of therapeutic opioids is laudable but does not protect against simple shift in drug of choice (or synthesis of new ones).

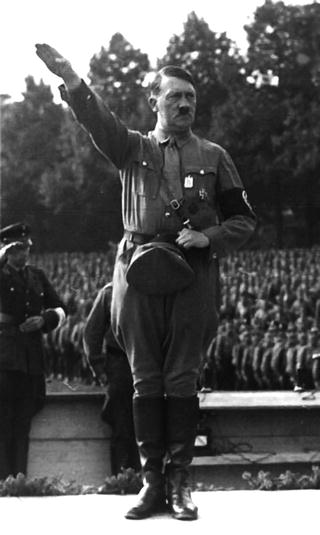

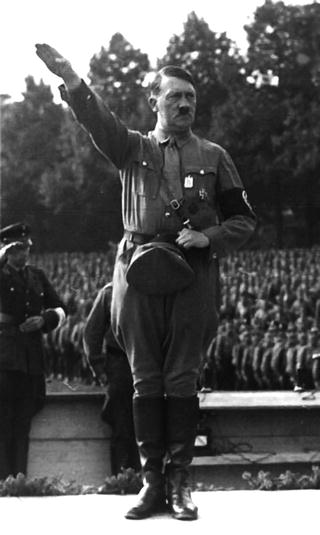

Reducing vulnerability/risk factors will be required if opioid dependence is to be attenuated. While this has been effectively achieved in the infectious disease world by conferring literal immunity to the agent, in the chronic noninfectious disease world such elegant solutions elude us. Literal vaccination to at least certain “strains” of the agent (e.g., oxycodone) has been explored in animal models [3, 4], and while this author personally finds the notion of elimination of that particular agent a goal worthy of any (Fig. 11.1) [5] and all efforts, it is unlikely to achieve individual- or population-level immunity. Opioid agent classes differ physically enough that immunoassays used for urine drug screening do not recognize molecules with sufficiently diverse chemical structure, and similarly artificial immunity to one class is unlikely to span phenanthrenes, phenylheptylamines, and phenylpiperidines, just as patients’ opioid allergies (another immune-mediated phenomenon) tend to be class specific. Furthermore, just as with reduction of availability, simple shift in drug of choice may occur as has been seen with the tremendous surge in heroin use over the past few years as prescription opioids become more difficult to procure.

Fig. 11.1

Oxycodone fueled the Führer [5]. By Bundesarchiv, Bild 146–1982-159-22A/CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 de, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6699198

Where widespread cultivation of actual humoral (antibody-mediated) immunity to exogenous opioids is possible, not only would this be undesirable in that it would render the host now unable to respond to therapeutic opioids, but their own endogenous opioids (β-endorphin, endomorphin) would likely also be rendered nonfunctional. Besides essentially conferring the individual to a life of misery not only from significant pathology but also potentially from inconceivable amplification/sensitization to pain, perturbation of the complex neuroimmunoendocrine system as it interfaces with the endogenous opioid system could result. Development of autoimmune sequelae is not inconceivable either.

Prophylactic mu-receptor antagonism (naltrexone in the water supply) could conceptually fall under the rubric of primary prevention but is neither without risk (hepatotoxicity, inability to respond to necessary therapeutic opioids) nor ethical challenge. This approach is however certainly effective and indicated in addiction recovery, and is discussed below at some length in the section on tertiary prevention.

Primary prevention as applied to opioid misuse and abuse must take the form of risk factor reduction. In a sense, modifiable risk factor reduction as discussed above in the case of chronic noninfectious diseases such as diabetes may be thought of to some degree as the development of behavioral immunity [6] to agents (e.g., simple sugars, sedentariness) that elicit or contribute to the pathophysiologic response of insulin resistance and the sequelae of sustained hyperglycemia.

Conferring behavioral immunity to opioid dependence must of course involve reduction or elimination of the desire to seek and use the drug, and this is most effectively achieved via both negative and positive motivators. Negative motivation in terms of the physician-patient relationship is limited essentially to education and includes instillation of respect and even fear of adverse consequences related to opioids (see Chap. 3). Human beings however are not always inclined to make the most logical decisions nor those in their own best interest, as Dostoevsky expresses so unapologetically:

Various health behavior models including the health belief model [8] note this universal observation that awareness of adverse consequences is not always enough to ensure healthy choices and behaviors. If the perceived benefits (alleviation of physical or emotional/psychological suffering deemed intolerable otherwise) outweigh perceived negative consequences (physical and psychological health, societal, legal) in the mind of the user, ongoing and progressive use will occur. Perceived susceptibility to and severity of a threat or negative outcome are not the only determinants of health-related (or other) choices; the belief in one’s ability to alter an outcome (self-efficacy) and the relative desirability thereof affect the behavior as well [8, 9].

“…when in all these thousands of years has there been a time when man has acted only from his own interest? What is to be done with the millions of facts that bear witness that men, consciously, that is fully understanding their real interests, have left them in the background and have rushed headlong on another path… another difficult, absurd way, seeking it almost in the darkness…” [7]

Psychological opinion (and the evidence underlying it) has been divided for decades as to whether punishment or reward is more effective at altering behaviors and choices; regardless it appears that both play an effective role in varying circumstances and presenting patients with all the data is rarely a bad thing.

Positive motivation for opioid avoidance may be instilled by promoting the benefits of a healthy lifestyle and non-opioid means of analgesia and pain management including behavioral strategies, complementary-alternative therapies in some cases, physiotherapy, and other pharmacology and procedural/operative interventions if appropriate. Even more beneficial to the patient is hearing themselves express these things. One of the techniques used in various counseling styles including motivational interviewing (described in greater detail below) is to help the patient/counselee identify and articulate their incentives both for and against instituting or at least pursuing a change of course; having the patient verbalize superseding goals excluding opioid use can be very beneficial to this end. The cultivation of self-efficacy and motivation has been well-documented as a critical component in behavioral change including cessation from substance use and misuse [10–12] and is presumably of positive benefit in prevention as well. While not drawn from the primary prevention literature, a study of 432 individuals from the 1991 to 1993 national Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Studies (DATOS) sample who completed 5 years follow-up [13] reported that addicts who successfully remained in recovery demonstrated statistically significantly greater perception of self-motivation toward that end; this was in fact the most important discriminating factor in the analysis. Regardless of whether that self-assessment represents a personality “predictor variable” (power of positive thinking) or a “dependent variable” following success, the literature [10, 14, 15] as well as common sense advocates for early and constant attention toward fostering personal initiative and motivation.

An obvious strategy for the prevention of opioid dependence is the efficacious treatment (or better yet, prevention) of pain—physical or otherwise—that might otherwise lead the patient to seek opioids. In psychological terms, this diminution/satisfaction of need is called drive reduction. An overview of prevention and rational/effective pain management addressing all salient pathologic contributors (including overall health deficiencies, organic “pain generator(s)” if applicable, and psychosocial dysfunction) was presented in Chap. 6. Given the primary role that the latter plays in the establishment of opioid dependence according to the literature and as discussed at some length in Chap. 10, the importance of effective behavioral health management in preventing opioid dependence cannot be overstated. Arguably, based on the strengths of association between other substance use disorders, anxiety, PTSD, various personality disorders, etc. and opioid dependence as discussed previously, the single most important aspect of primary prevention of opioid dependence may be aggressive psychosocial-spiritual screening and referral as indicated.

These strategies along with the motivational theories associated with them are presented in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1

Motivational approaches to opioid dependence prevention in the individual

Negative motivators aiding avoidance of opioid use | Positive motivators aiding avoidance of opioid use | |

|---|---|---|

Incentive theory (operant conditioning) motivators | Positive reinforcement/praise for healthy choices | |

Expectancy theory motivators | Education on adverse consequences of opioids | Education on benefits of opioid avoidance |

Drive theory motivators | Obviation of need through effective pain management and through optimizing psychosocial-spiritual health |

Environment is an epidemiologic concept not directly discussed to this point in the framework of this book and one that deserves focused consideration in the context of prevention. Environment in the classic epidemiologic triangle model encompasses any factors distinct from agent and host that influence the interaction between the two. In this book, the chief element of environment considered (given the target audience) has been the prescriber, conceptualized as vector. Other vectors exist of course, and beyond individuals responsible for the transmission of the agent, societal factors that influence both transmission and exposure behavior abound. Some of the more obvious environmental factors include legislation and regulation and public perception and the media. These latter, societal factors may represent the most important arena in which to target preventive efforts by educational campaigns. The impact of “peer pressure” upon behavior is well known to parents and the educational community and is not limited to children and adolescents. Humans are social creatures responding to, and for the most part adhering to norms (hence their existence and persistence) and cultivation of healthy respect/fear of opioids is arguably one of, if not the most important preventive strategies our nation can invest in. Analysis of numerous tobacco cessation campaigns at local and state levels have shown reduction rates as high as 60% in some communities, with most data showing 30–40% reduction [16]. The CDC’s 3-month “Tips from Former Smokers” television advertisement campaign resulted in an estimated successful increase in cessation for over 100,000 individuals [17].

Effective environmental intervention however must go beyond simple focus on opioid shunning/negative incentive; viable alternatives for coping with pain and distress (or even boredom) must be presented and instilled into the culture. Beginning with the healthcare environment and extending into the educational system, workplace, and even popular culture, prevention by healthy lifestyle (biopsychosocially and spiritually) is essential and must be championed and demonstrated. Simple education on the profound interactions between poor sleep quality, sedentary state, poor posture and ergonomics, diet, etc. upon pain may be moderately labor-intensive “up front” but pay dividends over the years. In our practice, we have created a systematic (yet tailorable to the individual) program focusing on these basics as well as recognizing and replacing cognitive distortions such as pain catastrophization. Beyond health promotion , interested parties at every level must also be trained to educate (and model) non-opioid means of managing the inevitable and ubiquitous human experiences of physical and psychological/emotional pain. Such an approach should not be restricted to traditional medical/psychological remedies such as pharmacotherapy, physiotherapy, procedures, and cognitive behavioral therapy but should incorporate consideration of and possibly referral for diverse elements including complementary/alternative medicine and “third wave” systems such as the mindfulness method [18]. Education on pain biology/pathophysiology itself (neurophysiology-focused rather than anatomic-based) has been shown in several trials to result in significant improvements in pain perception and functional improvements [19, 20]. Exposing patients to nascent concepts such as adaptive cortical neural plasticity may confer profound benefit in instilling self-efficacy and internal locus of control, which are critical to prevention of opioid-seeking.

While not conducive to a systematic/formulaic approach , in our practice we have found that after establishing rapport with patients, gentle redirection away from the quagmire of external locus of control/passivity and desire for instant gratification to a place of self-efficacy and acceptance—with concomitant improvement in perceived pain—is possible with adequate knowledge, skill, and compassion. “One size does not fit all,” and both content and sequence of counsel are highly individual. However, common elements include reassurance and education and gentle challenge/appeal to an ethic of toughness and courage, as well as encouragement toward establishment of community that can provide support and camaraderie.

It must be emphasized again that it is incumbent upon the physician to establish and maintain a good therapeutic relationship . While the merits or fallacies of the paternalistic medical model may be debated (in this author’s opinion we have drifted too far from the physician as physician), there is absolutely no justification for valuation of other human beings as inferior and not deserving of respect and compassion. The old dictum that “people don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care” may be nowhere more appropriate than in the realm of chronic pain and suffering, where patients have likely encountered multiple providers in their search for relief, some of whom are more callous and genuinely disinterested than others in the fellow human being seeking their help.

The often-quoted Alcoholics Anonymous phrase “Fake it until you make it” may be worth reminding oneself if compassion does not come naturally or is frequently fatigued. Fuel for such practice may come from the knowledge that not only patient outcome but also physician reputation and even avoidance of litigation are proportional to the degree of empathy and care perceived by the patient [21–25].

While certainly outside the scope of this book, while focusing on environment it would be gross oversight to neglect the observation that at least temporal correlation exists between a global increase in diagnosis of mental health disorders [26] and the rapid rise in psychoactive substance use. Again, while admittedly within the realm of observation and speculation, ignoring the temporal correlation between the unprecedented extensive changes in Western social structures (e.g., family, neighborhoods and community, centrality of organized religion) over the past three decades and the increasing use of drugs both prescription and illicit may be profoundly shortsighted. Indeed, the literature for the past four decades has supported the protective influence of family cohesion and community support [13, 27–30] upon both psychological health and well-being and reduced substance use and abuse, and spirituality/religion has shown consistent positive association toward those ends as well [13, 30–33].

The tremendous success of spirituality-focused and faith-based programs upon substance misuse reduction at least at the tertiary prevention level [13, 30–35] should engender at the very least investigation into the nature of their influence upon environment, as well as exploration of their utility within a comprehensive primary and secondary prevention strategy. In our practice, while respecting the beliefs of each individual, we also advise openness to spiritual issues that may be the missing link, so to speak, in addressing the underlying distress and otherwise unmet needs and drives motivating substance seeking. To neglect the opportunity for prevention of opioid dependence (in human beings who possess far more faculties and dimensions than rats) afforded by philosophic and religious/spiritual growth and development is arguably at least as shortsighted as ignoring the necessity of biological/somatic health maintenance.

Secondary Prevention

The concepts of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention form a useful paradigm for organizing thought and in many cases implementing intervention. In the “real world,” there is considerable overlap in both targeted populations due to a number of difficulties including lack of sensitivity/specificity of measurement as well as inability to categorize what may be a continuous variable. The application of preventive strategy/tactics is accordingly also “blurry.” While screening for disease is generally considered part of secondary prevention, in the context of opioid dependence (as with many other infectious and noninfectious conditions), screening for psychosocial diatheses or risk assessment as discussed at some length in the previous chapter is essential for identifying individuals at greater risk for the development of opioid dependence and therefore aiding in risk factor (pain, distress, opioid exposure) reduction. Given that opioid dependence may also in many cases represent a “remitting-relapsing” condition, such risk assessment and risk factor reduction play a role across the continuum.

Nonetheless, adherence to these categorical concepts is useful for organizing thought and at least population-level if not individually focused efforts. If primary prevention is essentially prevention, secondary prevention comprises detection and early treatment. Screening for opioid dependence was discussed at some length in the previous chapter and validated instruments for assessment of an individual’s risk of abuse both before initiating an opioid therapy trial and during treatment have been developed and are increasingly utilized in clinical practice. Such ongoing monitoring has been shown to be associated with reduced abuse and misuse [36].

When identified (or suspected), early treatment of opioid dependence must begin with frank and compassionate counseling, reassessment of risk-benefit ratio for ongoing therapy, and in most cases formulation of a plan for weaning and discontinuation (“exit strategy”). A commonly used program is to decrease total daily dose by 10–20% per week. Provision of alternate multimodal means of physical and psychological distress attenuation (including non-opioid analgesics, withdrawal symptom modifying agents such as clonidine, etc.) is generally necessary but should not be limited to the pharmacologic. Direct counseling and encouragement from the provider as well as enlisting the help of behavioral health colleagues to facilitate self-efficacy is of the essence. The physician’s responsibility to the opioid-dependent patient does not end with simple opioid weaning and discontinuation; it remains incumbent upon us to offer rational and effective underlying pain issues by multimodal means as discussed in Chap. 6, while recognizing and communicating that often such an end will require a strategic lifestyle overhaul in multiple dimensions including but not limited to the physical and psychological.

While most effective when backed with science, effective opioid dependence counseling is an art that takes quite a bit of time and effort to develop proficiency in. In our experience and that of many clinicians, the “early”-stage opioid-dependent patient poses much more of a management challenge than the floridly “down-and-out” addict discussed in the next section. Such “mildly” dependent individuals who have not “hit rock bottom” (to borrow a phrase from grassroots peer support parlance) are generally much less likely to recognize and admit their dependence (perhaps due to less cumulative burden of adverse effects including work, social, and family consequences) and are often more resistant to discontinuation advice and efforts.

Motivational interviewing , developed by Miller and Rollnick [12], is one of the more widely practiced techniques in substance dependence counseling today and is highly relevant to clinical secondary (and tertiary) prevention of opioid dependence. Building on humanistic and self-actualization theories from Carl Rogers and others, motivational interviewing (MI) first helps the patient identify discrepancy between ideals and actions, and also ambivalence—the simultaneous presence of desire for and against something. It then seeks to assist the patient strengthen their fully informed and considered position for change and develop motivation and a plan for carrying this out. In our practice, we seek to use many of the principles of MI in helping patients recognize the obstacles to overcoming opioid dependence and the (sometimes subconscious) reasons they wish to remain in that state. These generally ostensibly begin as complaints of physical pain, but with gentle and skillful facilitation issues of emotional distress, restoration of an overall sense of well-being, and both hedonic/positive and withdrawal/negative reinforcements frequently come to light. It is generally easier to recognize and divulge motivations for change, and some of the more common ones expressed by patients include improvements in health, sense of accomplishment and self-esteem, the respect of others, salvaging a relationship or job, and so on. Once patients arrive at a place of honesty and security in articulating both motivations and counter-motivations/saboteurs (hearing oneself verbalize things is generally more powerful than hearing it from others) it is easier to guide them in a course of growing commitment to achieving freedom from opioid dependence.

As with primary prevention, helping patients “stay the course” with opioid weaning and discontinuation is greatly facilitated by effective physical and emotional pain reduction and possibly even more importantly, cultivation of resilience and self-efficacy. While these efforts are obviously best handled by counselors and psychologists, at least basic familiarity with the concepts and techniques are invaluable to the good physician who would help reinforce their patients’ healing and wellness.

Tertiary Prevention

Tertiary prevention comprises harm reduction and efforts to reduce consequences of established disease while continuing to attempt reversal. It is in essence synonymous with treatment.

Treatment of Opioid Addiction: General Considerations

The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) has published recommendations/standards for the treatment of the opioid-addicted patient [37]. ASAM has also published a National Practice Guideline for Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) of opioid addiction [38]; there are significant areas of overlap between the two documents; however, the latter communicates significantly greater detail regarding its subject matter and is discussed in greater detail below. Six main components of care are conceptualized within the standards as follows:

And while consideration of all aspects are certainly warranted in every clinical situation, their applicability and relative importance may vary.

Assessment and diagnosis

Withdrawal management

Treatment planning

Treatment management

Care transitions and coordination

Continuing care management

The first component, assessment and diagnosis, should be comprehensive, addressing not only traditional biopsychosocial variables (including substance use history) and addiction history but should also include a “multidimensional assessment” of factors that may facilitate or impede recovery as outlined in the ASAM Treatment Criteria for Addictive, Substance-Related, and Co-occurring Conditions [39]. The six dimensions assessed include:

Acute intoxication and/or withdrawal potential

Biomedical conditions/complications

Emotional/behavioral/cognitive conditions and complications

Readiness to change

Relapse/continued use/continued problem potential

Recovery environment

Physical examination and pertinent laboratory assays should be performed.

The second component, withdrawal management begins with assessment of withdrawal potential or severity if already in process, and must take into account other substances that the patient may be withdrawing from (or intoxicated by) that may complicate treatment decisions and placement recommendations. A decision to palliate withdrawal symptoms and treat potentially harmful consequences and initiate antagonist therapy vs. induction onto full or partial agonist therapy must be made. Typical opioid withdrawal symptoms may be managed with clonidine, antiemetics and antidiarrheals, non-opioid analgesics, and possibly benzodiazepines bearing in mind the increased risks of these drugs both short and long term.

The third and fourth components, treatment planning and management, involve a comprehensive and ongoing determination of benefit-risk ratios from all relevant psychosocial and pharmacological therapies and formulation and implementation of an individualized plan based on multidimensional assessment. Coordination of care among various disciplines and involvement of social support networks including family when available and appropriate are key elements.

The fifth component , care transitions and coordination, involves ensuring appropriate and smooth transitions between levels of care based on comprehensive assessment including history of responses to previous treatment efforts. This may be in response to therapeutic failure or success, with lateral, higher or lower-echelon care depending on treatment response. It is incumbent upon the addictionologist to obtain proper authorization for release of information and to ensure salient information transfer to other providers while complying with all confidentiality requirements.

The sixth element, continuing care management, is oriented toward outlining and ensuring facilitating sustainable recovery self-care upon meeting treatment goals. It is justifiable and in the patient’s best interest, given the frequently relapsing nature of addiction to provide ongoing monitoring and periodic “wellness checks.”

Treatment of Opioid Addiction: Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT)

Prior to widespread appreciation of the prescription opioid epidemic and focusing on illicit (e.g., heroin) abuse, a National Institutes of Health consensus panel in 1997 [40] advised:

With the rise of the prescription opioid epidemic, further support for implementation of MAT has been provided at a congressional level with the passage of the 2008 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) and the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA.) The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA ), ASAM and international organizations such as the World Health Organization all champion the use of MAT as part of a comprehensive recovery/rehabilitation strategy in appropriately selected patients [38, 41–43].

a commitment to offer effective treatment for [opioid addiction] for Federal and State efforts to reduce the stigma attached to MAT and to expand MAT through increased funding, less restrictive regulation, and efforts to make treatment available in all States.

Systematic reviews performed within the last decade have shown that MAT is effective in attenuating opioid use disorder, whether illicit or prescription [44–47]. Studies addressing efficacy generally consider the outcome of reduction in opioid use (other than medications used in treatment) as evidenced by self-report and/or urinalysis or the outcome of retention in treatment. However, in this author’s opinion, these outcomes should be “taken with a grain of salt” or at least evaluated in the context of greater multivariate analysis, as compliance with substitution therapy or retention in programs offering essentially low- or no-cost maintenance of dependence/addiction may not accurately reflect improvement in opioid use disorder. Timko et al. [47] reported increased treatment retention for methadone compared to buprenorphine and heroin compared to methadone. This begs the question, of course, of what we are really trying to accomplish with MAT. A recent thought-provoking article exploring different perspectives on treatment duration/retention highlighted the importance of considering outcomes of sobriety/“freedom [from] dependence” and self-determination when evaluating MAT strategies [48].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree