Acute Vision Loss

Catherine A. Marco

Loss of vision, whether unilateral or bilateral, partial or complete, is an emergent ophthalmologic complaint and requires rapid and thorough evaluation and management. Major eye diseases are particularly common among the geriatric population with the predominant disease entities affecting this group including diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, and macular degeneration. Approximately 50% of patients older than age 65 have a major eye disease (1). Emergent evaluation includes taking the relevant ocular history, examination of the eyes and other relevant systems, pertinent laboratory evaluation, determination of the differential diagnosis, and rapid institution of appropriate therapy. Consultation with an ophthalmologist and/or other appropriate specialists is often indicated.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Patients may present with complete or partial vision loss, with or without a variety of associated symptoms. Typically, any degree of visual loss is disturbing to the patient and may lead to early evaluation; however, some patients may procrastinate and not seek medical evaluation. A thorough history can be crucial and is the most efficient approach to the wide differential diagnosis of visual disturbances.

Several historic points may be particularly useful in determining the etiology of symptoms. The onset of symptoms, whether gradual or abrupt, transient or persistent, constant or waxing and waning, may be of importance. The unilateral or bilateral nature of the disturbance, and association of pain, may be valuable in the differentiation of certain disorders. Associated symptoms, including systemic symptoms (fever, weakness, rash, etc.), previous history of similar symptoms, history of trauma, and other ocular symptoms, including eye pain, redness, discharge, and so forth, should be sought when obtaining historical information from the patient. Following is a discussion of many conditions that cause vision loss.

Inflammatory Processes

Giant Cell Arteritis

Giant cell arteritis (GCA), an inflammatory disease of medium and large arteries, typically affects patients older than 60 with a female predominance of 3:1. Peak incidence occurs between the ages of 70 and 80. GCA is often associated with polymyalgia rheumatica (2). Visual disturbances are a common presenting symptom and may include painless visual loss or cranial nerve palsies. Patients may also present with malaise, headache, neck pain, fever, night sweats, anorexia, weight loss, depression, jaw claudication, or pain over the temporal or occipital arteries (Table 58.1). Helpful diagnostic tests include an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (typically 80 to 100 mm within the first hour; elevated in 98% of documented cases), elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), and an abnormal temporal artery biopsy (3). Elevated ESR has a sensitivity of 76% to 86%, and elevated CRP has a sensitivity of 97.5%. The sensitivity of ESR and CRP together is 99% (4).

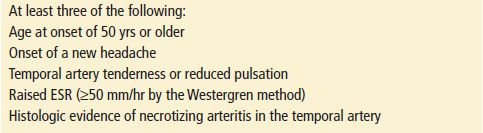

TABLE 58.1

Diagnostic Criteria for Giant Cell Arteritis (5)

Optic Neuritis

Optic neuritis is an inflammatory disorder that often affects young women and occurs from varying etiologies, including multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, leukemia, syphilis, collagen vascular diseases, alcohol abuse, tumor, and infection (meningitis, syphilis, Lyme disease, viral infection). Optic neuritis is often the initial manifestation of multiple sclerosis. Acute visual loss, often occurring within 1 week, is typical. Most patients (65%) have pain with eye movement. Typically, there is unilateral involvement and an afferent pupillary defect. Elevation of the optic disc may be seen on funduscopic examination. Visual field defects may be noted. Optic neuritis often resolves spontaneously over weeks to months (6).

Uveitis

Uveitis, inflammation of the iris, ciliary body, or choroid, may cause visual impairment. Uveitis may be caused by Reiter syndrome, ankylosing spondylitis, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, collagen vascular disorders, and other diseases. Uveitis may also present as an inflammatory response to corneal abrasion, ulcer, infection, or trauma. The presentation generally includes conjunctival injection, pain, photophobia, and blurred vision.

Vascular Events

Central Retinal Artery Occlusion

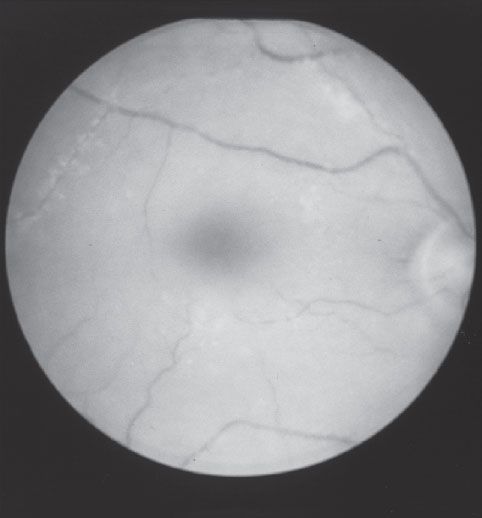

Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) often presents with sudden, painless visual loss (Fig. 58.1). There may be a history of transient visual loss prior to this event. The cause is often due to emboli from carotid plaques, cardiac valves, fat emboli, arteriosclerosis, or a host of other underlying disorders (such as systemic lupus erythematosus), hypotension, coagulopathy, migraine, smoking, hypercholesterolemia, procedures such as cardiac catheterization, sickle cell disease, cocaine, certain medications (sildenafil, oral contraceptives, epinephrine, etc.), amniotic fluid embolism, and GCA. Elderly patients are more commonly affected, and men are more commonly affected than women. Visual loss is typically profound, with 90% of patients sustaining losses that range from counting fingers to light perception. An afferent pupillary defect may be present. Physical findings include “cherry-red spot” of the fovea, retinal opacity in the posterior pole, “boxcars” of the arterioles, pallor of the involved retina, and optic disc edema (7). Ultrasound, including color Doppler imaging, may be helpful in elucidating the diagnosis (8). Echocardiography and carotid artery studies may reveal sources of emboli. Branch retinal artery occlusion (RVO) may occur and may present with sudden loss of visual field and reduction in visual acuity. The long-term prognosis is related to the duration of symptoms prior to resolution. Improved outcomes are seen if the condition is reversed within 90 minutes of onset of symptoms.

FIGURE 58.1 Central retinal artery occlusion.

Central Retinal Vein Occlusion

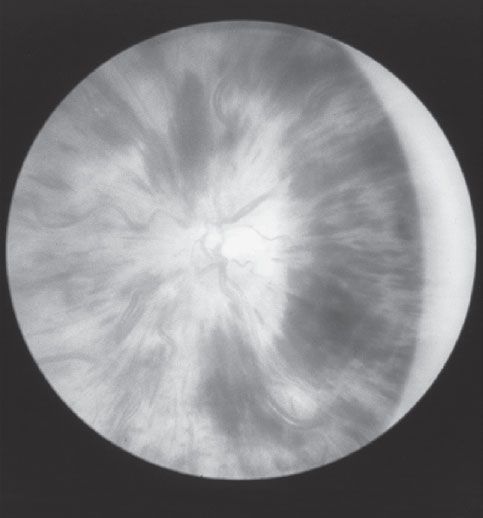

Patients with central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) typically present with painless, sudden loss of vision (Fig. 58.2). Most patients are older than age 50, and many also have significant cardiovascular disease. Other associated disorders include hypertension, glaucoma, venous stasis, diabetes mellitus, tobacco use, vasculitis, and collagen vascular disorders. Physical findings may include retinal hemorrhage, which may be pronounced and diffuse, venous dilatation, cotton wool spots, and optic disc edema. Branch RVO may occur and may have segments of intraretinal hemorrhage. Complications may include macular edema, ischemia, and neovascularization with associated vitreous hemorrhage. The natural history of CRVO is often favorable even without specific intervention.

FIGURE 58.2 Central retinal vein occlusion.

Amaurosis Fugax

Amaurosis fugax, a unilateral transient obstruction of a retinal artery, may cause temporary loss of vision (up to 15 minutes). The visual loss is often described by the patient as a curtain being drawn across the visual field. Amaurosis fugax is usually caused by cholesterol emboli or fibrin-platelet emboli and may be associated with carotid artery disease, cardiac arrhythmias, anemia, sickle cell disease, hypertension, or episodic hypotension. Carotid and cardiac studies may be indicated to determine the source of the emboli.

Ischemic Optic Neuropathy

Ischemic optic neuropathy is typically found in patients older than 50 and often presents with painless decreased visual acuity. This disorder may result from an infarction of the optic nerve (90% of cases) or from GCA (10% of cases). An afferent pupillary defect may be found as well as a pale, elevated optic disc.

Vitreous and Retinal Disorders

Vitreous Hemorrhage

Vitreous hemorrhage typically presents with acute unilateral painless loss of vision and may be accompanied by symptoms of “floaters” or “cobwebs.” Associated visual disturbances may be mild or severe, depending on the extent of the hemorrhage. The normal red reflex of the fundus is absent. Diffuse, dark, particulate opacities may be seen. If severe, a black uniform reflex (“eight-ball hemorrhage”) will be seen instead of the normal retinal red reflex. Vitreous hemorrhage may be associated with numerous disorders including diabetes, trauma, malignancy, vitamin K deficiency, CRVO, leukemia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia.

Diabetic Retinopathy

Diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause of visual loss among retinal vascular disorders and may be divided into proliferative and nonproliferative disorders. This disorder may occur in type I or type II diabetes mellitus. Nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy is a progressive microangiopathy. Symptoms may be mild or nonexistent and may include hue discrimination abnormalities, scotomas, contrast sensitivity, or a variety of other visual complaints. Physical findings include multiple hemorrhages throughout the retina and macular edema. Proliferative retinopathy refers to ischemia as a result of microvascular occlusions and may present with cotton wool spots, retinal vein bleeding, and irregular dilation of the retinal capillary bed. Sudden visual loss may occur with massive vitreous hemorrhage from fragile neovascularization or from retinal detachment. Progressive loss of vision may be slowed or prevented by laser photocoagulation.

Retinal Detachment

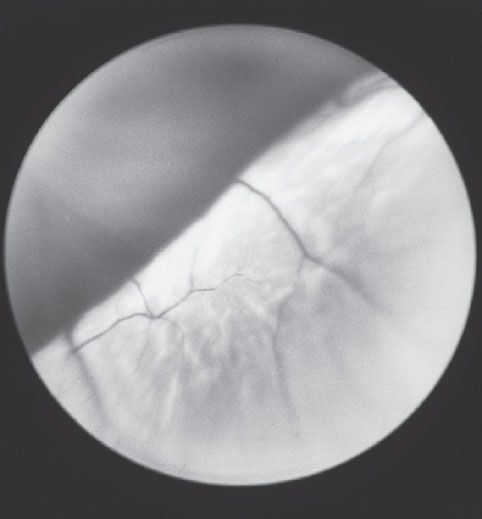

Retinal detachment refers to a separation of the two layers of the retina: the pigment epithelium and neurosensory retina (Fig. 58.3). The most common type, rhegmatogenous, occurs as a result of tears, holes, or breaks in the sensory layer of the retina. Retinal detachment may be associated with advancing age, male gender, significant myopia, diabetes mellitus, sickle cell disease, or ocular contusion or penetrating injury, or it may be idiopathic. In addition, exudative or traction types of retinal detachment may be seen. Symptoms include photopsia (light flashes), floaters, or a shower of black dots in the periphery secondary to hemorrhage into vitreous humor, or a sensation of a shadow or curtain obscuring the visual field. Visual acuity may be normal if the macula is unaffected or severely impaired if involved. On examination, the detached area may appear gray, opaque, or translucent. Retinal folds may be seen, and vessels may appear dark red. Symptoms often resolve within 1 week.

FIGURE 58.3 Retinal detachment.