INTRODUCTION

Acute peripheral neurologic lesions are a diverse group of disorders. By definition, they involve injury or disease in sensory and motor fibers outside of the central nervous system (CNS) extending to the neuromuscular junction. The peripheral nervous system (PNS) serves sensory, motor, and autonomic functions. Thus, the patient with a peripheral nerve lesion may have deficits in any combination of these functions. Exclude central processes, such as stroke or spinal cord injury, before considering an acute peripheral lesion.

DISTINGUISHING CENTRAL AND PERIPHERAL LESIONS

Use CNS and PNS neuroanatomy principles to distinguish lesions. Peripheral nerves contain varying amounts of motor, sensory, and autonomic fibers and follow well-described paths that make them prone to typical injuries. Thus, peripheral nerve lesions are more likely to be confined to one limb and to present with the involvement of multiple sensory modalities and motor symptoms. A typical example would be a nerve compression syndrome presenting with weakness, numbness, and tingling that developed after the arm was held in an unusual position for a prolonged period. However, weakness and numbness can be seen in both peripheral and central disorders. Hyporeflexia sometimes occurs with acute central lesions, but hyperreflexia and spasticity invariably develop with time. PNS disorders, like CNS diseases, can affect bulbar structures, resulting in diplopia, dysarthria, or dysphagia. Despite the overlap, CNS disorders have other features not seen in peripheral disease. For example, aphasia, apraxia, and vision loss are hallmarks of cortical disease. Most CNS lesions will result in upper motor neuron signs: hyperreflexia, hypertonia (spasticity), and extensor plantar (Babinski) reflexes. Perhaps the most important distinguishing component is the examination of deep tendon reflexes. Dorsiflexion of the great toe with fanning of remaining toes and flexion of the leg is a pathologic Babinski’s sign, indicating a central disruption of the pyramidal tract. Although there can be many similarities between patients with CNS and PNS lesions, the distinctions are clear (Table 172-1). Lateralization of weakness, hyperreflexia, positive Babinski’s sign, or any other CNS finding requires further investigation for a central rather than peripheral disorder.

| Central | Peripheral | |

|---|---|---|

| History | Cognitive changes Sudden weakness Nausea, vomiting Headache | Weakness confined to one limb Weakness with associated pain Posture- or movement-dependent pain Weakness after prolonged period in one position |

| Physical Examination | ||

| Reflexes | Brisk reflexes (hyperreflexia) Babinski’s sign Hoffman’s sign | Hypoactive reflexes Areflexia |

| Motor | Asymmetric weakness of ipsilateral upper and lower extremity Facial droop Slurred speech | Symmetric proximal weakness |

| Sensory | Asymmetric sensory loss in ipsilateral upper and lower extremity | Reproduction of symptoms with movement (compressive neuropathy) All sensory modalities involved |

| Coordination | Discoordination without weakness | Loss of proprioception |

LOCALIZING PERIPHERAL NERVE LESIONS

Patients with peripheral nerve disorders frequently require diagnostic evaluation unavailable during the initial ED encounter. A careful history and physical examination will exclude critical diagnoses and point toward the appropriate management.

The elements required to localize the process will usually include the following: symmetry; proximal versus distal symptoms; sensory, motor, or autonomic involvement; and mono- versus polyneuropathy. Sensory symptoms may include numbness, tingling, dysesthesias, pain, or ataxia. Motor symptoms manifest as weakness. Autonomic disability may present as orthostasis, bowel or bladder dysfunction, gastroparesis, or sexual dysfunction. Associated findings will frequently narrow the differential diagnosis or suggest a specific diagnosis. For example, in the setting of a recent viral infection or vaccination, consider Guillain-Barré syndrome. Is there a history of diabetes or subacute trauma? Does the patient with thrush or wasting and undiagnosed immunodeficiency have a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated neuropathy? Patients with an attached tick may have tick paralysis.

Perform a comprehensive neurologic examination on patients with peripheral nerve disorders, paying particular attention to the specific area and distribution involved. Evaluate for hypotonia, muscle wasting, fasciculations, and hyporeflexia. Is there focal weakness? What is the perception of light touch, vibration, and position sense? If there are sensory deficits, what spinal nerve levels do they involve?

Many patients with peripheral nerve disorders will require electromyography and nerve conduction velocity studies. Electromyography is used to differentiate primary muscular or neuromuscular junction problems from peripheral nerve disorders. Nerve conduction velocity studies, which measure the speed of conduction by observing the response to nerve stimulation by distally placed electrodes, can differentiate between axonal loss and demyelination. Combined with the history and physical examination, these tests allow the consultant to better localize the lesion and make a firm diagnosis. Lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis are frequently required to confirm the diagnosis in acute or subacute inflammatory and infectious processes. In certain cases, nerve biopsy may be required. In cases where biopsy is considered, MRI can direct the biopsy site to the area of greatest utility.

Management of PNS disorders depends on the specific diagnosis. However, a few general principles apply. Initiate supportive care for severe, life-threatening neuromuscular diseases in the ED. Monitor patients with the potential for respiratory failure, aspiration, and cardiac dysrhythmias. For patients at risk for diaphragmatic failure, measure baseline forced vital capacity or negative inspiratory pressure in the ED to assess whether there is an immediate need for respiratory support or admission to an intensive care unit. Admit patients with acute peripheral neurologic conditions if there is potential respiratory or autonomic compromise, or with severe or rapidly progressing weakness. If a peripheral disorder is suspected and the patient does not require admission, arrange for neurologic follow-up within 7 to 10 days.

ACUTE PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHIES

Guillain-Barré syndrome is an acute polyneuropathy characterized by immune-mediated peripheral nerve myelin sheath or axon destruction. The prevailing theory is that antibodies directed against myelin sheath and axons of peripheral nerves are formed in response to a preceding viral or bacterial illness. Symptoms are at their worst in 2 to 4 weeks, and recovery can vary from weeks to a year.

Classically, Guillain-Barré syndrome is preceded by a viral illness, followed by ascending symmetric weakness or paralysis and areflexia or hyporeflexia. Paralysis may ascend to the diaphragm, compromising respiratory function and requiring mechanical ventilation in one third of patients. Autonomic dysfunction may be present as well.

There are several variants of Guillain-Barré syndrome. The Miller-Fisher syndrome variant is associated with Clostridium jejuni infection. It is preceded by diarrhea and is characterized by ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, and decreased or absent reflexes. Weakness is less severe and the disease course is milder than Guillain-Barré syndrome. Antibody testing for C. jejuni can confirm the diagnosis. Acute motor axonal neuropathy is a pure motor variant, also associated with C. jejuni infection, and is seen in Japan and China. Another variant is acute motor and sensory axonal neuropathy, with loss of both motor and sensory function. This variant begins abruptly, progresses rapidly, and has a prolonged course and poor prognosis.

The diagnosis is mostly historical, but lumbar puncture and electrodiagnostic information can improve confidence in the diagnosis. Table 172-2 lists the specific diagnostic criteria.

Required

Suggestive

|

CSF analysis shows high protein levels (>45 milligrams/dL) and WBC counts typically <10 cells/mm3, with predominantly mononuclear cells. When there are >100 cells/mm3, other considerations include HIV, Lyme disease, syphilis, sarcoidosis, tuberculous or bacterial meningitis, leukemic infiltration, or CNS vasculitis. Electrodiagnostic testing demonstrates demyelination. Nerve biopsy reveals a mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate. If MRI is performed to rule out alternative diagnoses, it will show enhancement of affected nerves.

The first step in management is assessment of respiratory function. Airway protection in advance of respiratory compromise decreases the incidence of aspiration and other complications. A well-established monitoring parameter is vital capacity, with normal values ranging from 60 to 70 mL/kg. A simple bedside assessment of respiratory status is obtained by trending values reached when the patient counts from 1 to 25 with a single breath. Avoid depolarizing neuromuscular blockers like succinylcholine for intubation in Guillain-Barré syndrome due to the risk of a hyperkalemic response.

Both IV immunoglobulin and plasmapheresis shorten the time to recovery. Neither has been shown to be superior to the other, nor are they more efficacious when used together. There are adverse effects seen with both modalities of treatment. IV immunoglobulin has been associated with thromboembolism and aseptic meningitis; plasmapheresis is associated with hemodynamic instability, but a lower rate of relapse. In general, IV immunoglobulin is more widely available and less cumbersome to administer. Corticosteroids are of no benefit and may be harmful.1

Admit patients with acute Guillain-Barré syndrome to a unit where cardiac, respiratory, and neurologic functions can be monitored. Even if a patient does not initially meet the criteria for intubation, intensive care unit admission may still be indicated in order to avoid sudden, unmonitored respiratory failure (Table 172-3).2

Indications for intubation Vital capacity <15 mL/kg Declining one breath count Pao2<70 mm Hg on room air Bulbar dysfunction (difficulty with breathing, swallowing, or speech) Aspiration Indications for admission to intensive care unit Patients with 4 or more of the following findings: inability to stand, inability to lift the head, inability to lift the elbows, insufficient cough, time from symptom onset to hospital admission <7 days or elevated liver enzymes Autonomic dysfunction Bulbar dysfunction Initial vital capacity <20 mL /kg Initial negative inspiratory force less than –30 cm of water Decrease of >30% of vital capacity or negative inspiratory force Inability to ambulate Treatment with plasmapheresis |

Bell’s palsy or idiopathic facial nerve palsy is the most common cause of unilateral facial paralysis. There are 23 to 25 cases per 100,000 annually, affecting men and women equally. Cranial nerve VII, the facial nerve, supplies motor innervation to the muscles of expression of the face and scalp, the stapedius muscle, and taste to the anterior two thirds of the tongue. The cause of Bell’s palsy is not clear. Herpes simplex virus DNA and antigens have been discovered around the facial nerve of affected patients. However, antiviral medications are ineffective, casting doubt on the once predominant theory that herpes simplex virus is responsible for the disease.

Idiopathic Bell’s palsy may be preceded by pain around or behind the ear. Onset of facial paralysis is acute, with maximal symptoms in 2 to 3 days. Facial numbness or hyperesthesia can accompany paralysis. Subtle dysfunction of cranial nerves V, VIII, IX, and X may be associated; for example, patients may also complain of decreased taste or hyperacusis due to paralysis of the stapedius muscle. On exam, patients will have facial droop, effacement of wrinkles and forehead burrows, and inability to completely close the eye. Recurrent idiopathic Bell’s palsy occurs in a small number of patients.

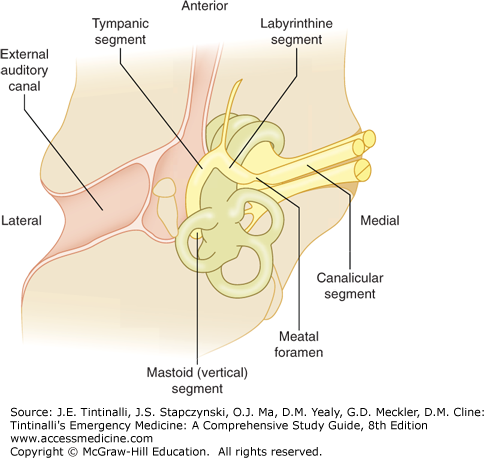

Diagnosis of idiopathic Bell’s palsy is based on the history and physical exam and is a diagnosis of exclusion of other conditions that can cause facial palsy. The most important alternative diagnoses to exclude are ear infections and stroke. Always perform an ear examination to identify otitis media and malignant otitis, and palpate the mastoids for tenderness, because infections of the ear and mastoids can affect the mastoid, tympanic, labyrinthine, or meatal segments of the cranial nerve VII (Figure 172-1).

When a central process causes facial paralysis, the forehead will be spared, as the forehead is supplied by cranial nerve VII arising near the pontomedullary junction, with crossed innervation. Peripheral facial nerve palsies will manifest as weakness throughout the facial nerve distribution, including the forehead. Middle cerebral artery ischemia or stroke consists of hemiparesis, facial plegia sparing the forehead, and sensory loss all contralateral to the affected cortex. Rarely, a brainstem stroke may mimic Bell’s palsy if the stroke affects the area where the facial nerve wraps around the abducens (cranial nerve VI) nucleus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree